Nebraska (album)

| Nebraska | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | September 30, 1982 | |||

| Recorded | December 17, 1981, to January 3, 1982, except "My Father's House", May 25, 1982 | |||

| Studio | Springsteen's home in Colts Neck, New Jersey | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 41:02 | |||

| Label | Columbia | |||

| Producer | Mike Batlan (engineer)[a] | |||

| Bruce Springsteen chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Nebraska | ||||

| ||||

Nebraska is the sixth studio album by the American singer-songwriter Bruce Springsteen, released on September 30, 1982, by Columbia Records. Springsteen recorded the songs as solo demos using a four-track recorder in the bedroom of his home in Colts Neck, New Jersey, intending to rerecord them with the E Street Band, but decided to release them as they were after full-band renditions were deemed unsatisfactory. Seventeen songs appeared on the tape, ten of which appeared on Nebraska, while others appeared in full-band renditions on the follow-up album Born in the U.S.A. (1984) and as B-sides.

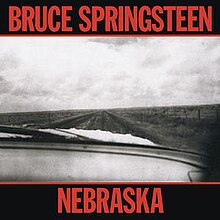

Living isolated in Colts Neck, Springsteen was influenced by American literature, films, and folk music when writing the Nebraska songs. The short stories of Flannery O'Connor particularly inspired him to write about his own childhood memories. Featuring a stark, lo-fi sound, the tracks tell the stories of ordinary, blue-collar individuals who try to succeed in life but fail at every turn, going in search of deliverance that never comes. Some are told through the eyes of outlaws and criminals, such as the killer Charles Starkweather on the title track. The album's cover artwork, taken by David Michael Kennedy, depicts a black-top road under a cloudy sky through the windshield of a car.

Nebraska stylistically stood apart from other releases in the year. Commercially, it sold well, peaking at number three in the U.S. It was accompanied by two European singles—"Atlantic City" and "Open All Night"; the former was supported by Springsteen's first music video. Springsteen did not promote the record, believing listeners should experience it for themselves. On release, critics praised the album as brave and artistically daring and Springsteen's most personal record up to that point. Negative reviews felt the songs stylistically merged together and its dark themes would appeal to fans only. The album appeared on several year-end lists.

Retrospective reviewers call Nebraska a masterpiece and one of Springsteen's finest works, being applauded as a timeless record that has lost none of its power since its release. It has appeared on lists of the greatest albums of all time. Nebraska proved influential in home recording, being recognized as one of the first DIY records released by a major artist and influencing the indie rock and underground music scenes. Numerous artists have paid tribute to the album and have cited its impact on their music. It has also inspired films and literature; a feature film based on the album's making will star Jeremy Allen White as Springsteen.

Background and development

[edit]

Bruce Springsteen's fifth studio album The River was released in October 1980.[5] The album and supporting tour brought Springsteen and the E Street Band their largest amount of commercial success yet.[6] Nevertheless, his newfound attention led him to look inward about his role as an entertainer.[7] Springsteen later explained that The River's success led to him dealing with "very conflicted feelings about being so separate from the people that I'd grown up around and that I wrote about".[8] At the end of the tour, he retreated to his newly-rented ranch in Colts Neck, New Jersey, in September 1981.[9][10]

Living isolated in Colts Neck,[11] Springsteen engrossed himself in American history, reading books and watching films in search of stories to use for songwriting.[12][13] Books he read included Joe Klein's Woody Guthrie: A Life (1980), Howard Zinn's A People's History of the United States (1980), The Pocket History of the United States, and Ron Kovic's autobiography Born on the Fourth of July (1976),[7] while films he watched included John Ford's adaptation of The Grapes of Wrath (1940), Terrence Malick's Badlands (1973), John Huston's adaptation of Wise Blood (1979), and Ulu Grosbard's True Confessions (1981).[14][15] Springsteen also began reflecting on his own childhood and studied the romans noirs of James M. Cain and Jim Thompson, the Gothic short stories of Flannery O'Connor, and the music of the singer-songwriters Guthrie, Bob Dylan, and Hank Williams.[b][17] Consequence of Sound's Bill See says that from these sources, Springsteen retrieved "a humanity and a curiosity about why certain people lose connection with themselves, their families, their community, [and] their government".[14]

O'Connor's writings were particularly influential on Springsteen.[18] The author and critic Dave Marsh said that Springsteen became impressed by the "minute-precision" of O'Connor's prose and believed that he had felt that his songwriting had been too vague, too "dreamlike",[19] instead wanting to write songs that were more detailed and concrete, away from the "clash and babble of metaphor" found occasionally on his previous albums.[20] O'Connor wrote some of her stories from a child's perspective,[21] which inspired Springsteen to write songs in a similar manner. Springsteen himself stated that the songs from the period were more "connected" to his childhood than ever before.[22][23] O'Connor's Catholicism was also an influence.[24] Springsteen stated in his 2003 book Songs: "Her stories reminded me of the unknowability of God and contained a dark spirituality that resonated with my own feelings at the time."[15] Songs written during the period featured stories ranging from Springsteen's childhood to ones about criminals and violence, as well as one about a Vietnam veteran returning home from the war to an unenthusiastic response.[25][26]

Recording

[edit]Colts Neck

[edit]Annoyed at how long it took him to record in the studio, Springsteen decided to record the new songs as solo demos, intending to rerecord them with the E Street Band – Roy Bittan (piano), Clarence Clemons (saxophone), Danny Federici (organ), Garry Tallent (bass), Steven Van Zandt (guitar), and Max Weinberg (drums) – at a later date.[c] He later told the author Warren Zanes: "The recordings were just meant to get us a jump start on work in the studio with the band. I'd always spent a lot of time writing in the studio. I was trying to be more efficient, I guess. Certainly trying to spend a little less money."[31]

Springsteen tasked his guitar technician, Mike Batlan, with buying a simple tape recorder to work out some demos and tinker with arrangements. Batlan picked up a four-track TEAC Tascam Portastudio 144 recorder,[13] a then-relatively new device[32] that allowed musicians to perform a basic track first before adding additional parts on the remaining tracks.[33][34][35] Springsteen believed these overdubbed instruments would help the band understand how the final track should sound.[36] He and Batlan set the recorder up in the bedroom of his Colts Neck home.[37] They connected the machine to two Shure SM57 microphones on stands.[38] Springsteen played a Gibson J-200 acoustic guitar,[39] overdubbing harmonica, percussion, mandolin, and glockenspiel.[40][41] The demos were recorded between December 17, 1981, and January 3, 1982.[d][45][46] Most of the basic tracks (vocals and acoustic guitar) were finished in four to six takes.[42]

Springsteen and Batlan mixed the sound by plugging the recorder into an Echoplex, a tape delay effects machine, and using an old water-logged Panasonic boombox[e] as a mix-down deck to bring the final mix onto a cassette tape.[48][49][45] In his 2003 book Songs, Springsteen stated he recorded this way because he "found the atmosphere in the studio to be sterile and isolating".[50] Fifteen songs appeared on the initial cassette tape: "Bye Bye Johnny",[f] "Starkweather"/"Nebraska", "Atlantic City", "Mansion on the Hill", "Born in the U.S.A.", "Johnny 99", "Downbound Train", "The Losin' Kind", "State Trooper", "Used Cars", "Wanda (Open All Night)", "Child Bride", "Pink Cadillac", "Highway Patrolman", and "Reason to Believe".[53][54][55]

Following mixing,[42] Springsteen sent the tape to his manager-producer Jon Landau with two pages of handwritten notes about arrangements and mixes.[48][53][55] According to the biographer Peter Ames Carlin, Landau was "impressed by the power of the songs' minimalist narratives" and the "yelping desperation in the performances".[42] In the subsequent months, Springsteen recorded two more songs at Colts Neck using the same recording methods: "The Big Payback", between March and April,[g][57] and "My Father's House", on May 25.[58][59]

Attempted rerecordings

[edit]In April 1982, Springsteen and the E Street Band rehearsed the demos at Bittan's house[45] before regrouping at the Power Station in New York City to rerecord them for release on the next album.[h][61][62] The band spent two weeks attempting full-band arrangements of the Colts Neck tracks but Springsteen and his co-producers—Landau, Van Zandt, and Chuck Plotkin—were dissatisfied with the results.[62][63][64] Springsteen, in particular, felt the full-band versions failed to capture the spirit of the demos,[65] while Plotkin blamed the studio's "tendency to conventionalize sounds".[66] Other songs from the tape, including "Born in the U.S.A.", "Downbound Train", "Child Bride" (rewritten as "Working on the Highway"), and "Pink Cadillac" proved successful in full-band arrangements.[54] Continuing into May, the band also recorded newly-written songs absent from the tape, including "Glory Days", "I'm Goin' Down", "I'm on Fire", "Wages of Sin", and "Johnny Bye-Bye".[i][70][71]

Despite the band's productivity and excitement about the recorded material, Springsteen remained focused on the rest of the Colts Neck songs.[72] Attached to the cassette's "authentic" sound,[73] he carried it with him in his jeans pocket, unsure of what to do with the material.[13][45] Throughout June, Springsteen and his co-producers began mixing and sequencing the acoustic and electric material as separate albums.[74] At some point, a decision was made to release the acoustic demos as is.[j][13][77] Springsteen briefly considered releasing a double album of acoustic and electric songs before deciding to release the acoustic ones on their own to give them "greater stature".[k] Van Zandt told Springsteen: "The fact that you didn't intend to release it makes it the most intimate record you'll ever do. This is an absolutely legitimate piece of art."[30] The acoustic album, titled Nebraska, became Springsteen's first and only album he made without knowing he was making a record.[81]

Springsteen's fans have long speculated whether the full-band recordings of the Nebraska material, nicknamed Electric Nebraska, will ever surface.[29][43] Having never appeared on bootlegs, it is among the most sought after of Springsteen's unreleased material.[82] In a 1984 interview with Rolling Stone, Springsteen believed an official release was unlikely, saying: "A lot of [Nebraska's] content was in its style, in the treatment of it. It needed that really kinda austere, echoey sound, just one guitar—one guy telling his story."[83] Decades later in 2006, Landau said that the electric release is unlikely because "the right version came out".[84] Nevertheless, in a 2010 interview with Rolling Stone, Weinberg praised the full-band renditions as "killing" and "very hard-edged".[85]

Mastering

[edit]Springsteen tasked the engineer Toby Scott with mastering the recordings, which proved problematic due to how he and Batlan recorded them.[86] According to Classic Rock Review, the demos were not recorded at optimal volume or with optimal noise reduction, meaning it was difficult to transfer the recordings to vinyl.[29] For weeks, Plotkin and Scott attempted to transfer the recordings to the mixing console in the Power Station with no success. Attempts at remixing Springsteen and Batlan's original mixes also failed. Plotkin and Scott eventually took the tape to different mastering facilities, with failed attempts by the mastering engineers Bob Ludwig, Steve Marcussen, and Greg Calbi.[87] After two months,[88] the final master was made at New York City's Atlantic Studios by Dennis King,[73] who was able to resolve the tape's low recording volume with noise reduction techniques.[43] In a 2007 interview, Scott explained: "[W]e ended up having Bob Ludwig use his EQ and his mastering facility, but with Dennis [King's] mastering parameters. And that's the master we ended up using."[89]

Music and lyrics

[edit]I wanted black bedtime stories. I thought of the records of John Lee Hooker and Robert Johnson, music that sounded so good with the lights out. I wanted the listener to hear my characters think, to feel their thoughts, their choices. [...] If there's a theme that runs through the record, it's the thin line between stability and that moment when time stops and everything goes to black, when the things that connect you to your world–your job, your family, friends, your faith, the love and grace in your heart–fail you.[90]

Nebraska represented a major stylistic departure for Springsteen,[4][79][91] although several songs from The River foreshadowed its direction,[80][92] including "Stolen Car", "The River", and "Wreck On the Highway".[13][79] Featuring only Springsteen,[93] Nebraska is a minimalist[94][95] folk record,[96][97][98] with folk rock,[96] heartland rock,[99] lo-fi,[95][100][101] and country influences.[102][103] Commentators have described its music and lyrics as stark,[l] bleak,[m] haunting,[112] somber,[113] depressing,[114] and brutal.[101] AllMusic's William Ruhlmann called the recordings themselves "unpolished" and sounding unfinished.[4] Consequence of Sound's Bill See noted the numerous "imperfections" in the mix,[30] including "the creaking of a chair, the "P's" that pop, the over-modulated harmonicas and Jimmy Rogers-like howls that pin the VU meters".[14] Joe Pelone of punknews.org argues that the album's lo-fi nature gives the songs a "hazy atmosphere" that "forces listeners to imagine more about what's going on, creating sounds that aren't there".[95] Springsteen explained: "My Nebraska songs were the opposite of the rock music I'd been writing. These new songs were narrative, restrained, linear, and musically minimal. Yet their depiction of characters out on the edge contextualized them as rock and roll."[23]

The songs on Nebraska tell the stories of ordinary, blue-collar individuals who try to succeed in life but fail at every turn.[14][79] Caught in the midst of existential crises, they realize that their lives are devoid of meaning and search for a deliverance that never comes.[18][96] Their desperation and alienation pushes them to commit unspeakable acts.[115][101] See noted the subservient role the working class characters have accepted through the use of the words "sir" and "son".[14] In their analyses of the album, the writers Ryan Sheeler and David McLaughlin state that the songs dissect the vulnerability of the American Dream, offering a harsh look on life through the eyes of outlaws, poor folk, and estranged families, and what happens when the pillars of life – work, love, family and friends – crumble and there is nowhere left to run.[101][104] Several commentators, including the critic Greil Marcus,[116] interpreted the album's stories and themes as reflections of America during the presidency of Ronald Reagan,[94][110][117] although Steven Hyden states that the songs were not "explicitly" or "implicitly" political, but were interpreted as such due to the timing of the album's release.[118] In his 1985 book on Springsteen, Robert Hilburn said the Nebraska songs were simply "an extension of the social concerns he began expressing on the River Tour".[119]

Stories told through the eyes of criminals include "Nebraska" and "Johnny 99",[120][121] as well as through Springsteen's own childhood memories on "Mansion on the Hill", "Used Cars", and "My Father's House".[58] Several songs are driven by automobiles.[13][122][103] Compared to Springsteen's previous records, where the car represented escape (Born to Run) and a place where stories unfolded (Darkness on the Edge of Town and portions of The River), cars on Nebraska represent a chamber that keeps its characters isolated,[13] or one they travel in while searching for some type of connection as the world passes them by.[101]

Side one

[edit]

The opening track, "Nebraska", tells the story of the killer Charles Starkweather,[96] who murdered ten people from 1957 to 1958 between Nebraska and Wyoming while traveling with his girlfriend Caril Ann Fugate.[n] After his capture, Starkweather is sentenced to death by electric chair but remains unrepentant, blaming his actions on the "meanness" of the world.[121][18] Springsteen wrote the song after watching Badlands, a film about the couple,[101] and reading the Ninette Beaver book Caril (1974).[124][121] The song is sung from a first-person perspective; Springsteen said in 2005 that "everyone knows what it is like to be condemned".[124] The song's music was described by Rolling Stone's Steve Pond as "gentle" and "soothing".[96]

"Atlantic City" follows the mob wars in the titular city.[96] At the time it was written in the early 1980s, Atlantic City was controlled by corruption and had turned to gambling in hopes of revitalizing the city. In the song, a young man struggles to make an honest living, forcing him and his girlfriend to relocate to the city so he can join the mob.[29][113][125] Springsteen mentions "the Chicken Man from Philly", which referred to the mafia boss Philip Testa, who was murdered in 1981.[29][126] Margotin and Guesdon note the song's "dense atmosphere and the performance's feeling or urgency".[125]

"Mansion on the Hill" evokes Springsteen's childhood memories, remembering a large mansion on top of a hill that piqued his curiosity, and car rides with his father.[127][128] Its title was taken from a Hank Williams song of the same name.[127] Like other songs on the album, the musical arrangement is minimal, with guitar and harmonica.[129] Margotin and Guesdon note "a spellbinding, hypnotic atmosphere" that is "filled with emotion and restraint".[127]

In "Johnny 99", the narrator is laid off from his job at the Ford assembly plant in Mahwah, New Jersey, and takes out his frustration by murdering a hotel clerk; he is captured and subsequently sentenced to 99 years in prison and begs for the death penalty.[o] Unlike the murderer in "Nebraska", the perpetrator on "Johnny 99" shows remorse for his action, saying he is "better off dead" due to his large debts and a house being foreclosed.[131] Musically, it features a rock'n'roll/rockabilly rhythm with echoed vocals and an ambient atmosphere.[130] AllMusic's William Ruhlmann describes Springsteen's performance as "raucous", one that starts with "lonely falsetto wails" and ends with "exuberant falsetto shouts".[120]

"Highway Patrolman" "juxtaposes the duty to carry out the law with the blood ties of family loyalty".[14] It tells the story of an honest police officer named Joe Roberts who is given a choice of turning his own brother in for committing a crime or letting him go, ultimately going with the latter.[93][132][133] Springsteen argues in the song's chorus, "Man turns his back on his family/Well, he just ain't no good."[132]

"State Trooper" is a lo-fi folk song led solely by vocals and guitar.[13][134] Classic Rock Review describes the guitar line as emulating "the recurring sound of the road".[29] Musically, the track was directly influenced by "Frankie Teardrop" by the synth-punk band Suicide.[13][134][135] Lyrically, the song is told from the point-of-view of a car thief;[135] he does not have a license or registration and becomes increasingly paranoid the farther he travels on a deserted highway.[29][136][134] The verses end with the driver's plea to a state trooper—either real or imaginary—not to stop him as he drives through the night.[135]

Side two

[edit]"Used Cars" uses Springsteen's childhood to describe his own experiences with his father and differences in social classes growing up.[137] Set to gentle music,[13] the narrator watches his father purchase a used car as the family cannot afford a new one.[14] The father, worn from years of manual labor and ashamed of his poor income, is unable to share his feelings with his son.[13][128] The family shows off their "brand new used car" to the neighbors, after which the narrator clings to the hope that he can escape from this reality and win the lottery, vowing he is "never gonna ride in no used car again".[14][138][128]

"Open All Night" has a more light-hearted mood compared to the rest of the album, being an up-tempo rock song with a Chuck Berry-style melody and rhythm.[p] The singer wants to be delivered from nowhere, but requests that rock and roll music accompany his long journey driving down the New Jersey Turnpike.[93][139][141] The song was inspired by an unnamed short story by the novelist William Price Fox.[140]

"My Father's House" is the final song on the album relating to Springsteen's childhood.[96][58] It returns to a sadder mood,[58] wherein the narrator has a dream in which, as a child, he is saved by his father from dark forces in a forest. Upon waking up, he decides to reconcile with his estranged father.[128] When the narrator arrives at his father's house, the narrator finds he no longer lives there, with his dreams of making peace with his father crushed.[58]

The album's closing track, "Reason to Believe", Springsteen tells four short stories across four verses:[141] a man hopes to revive a dead dog on the side of a highway by poking it; a woman waits at the end of a road for a man who never comes; a child is born and a man dies; and a groom waits for bride who stood him up.[96][114] The verses are unified by the singer's humorous outlook that individuals always find "some reason to believe".[114] The author Rob Kirkpatrick argues that the song's point is that "people endure, that they struggle against all evidence to the contrary, because it's the only thing that they can do—or else they end up dead, spiritually or literally".[142] According to the writer Irwin Streight, the song "seeks to resolve the litanies of meanness, desperation, hopelessness, and longing recounted in the preceding stories, and to resolve them in a decidedly Catholic fashion".[18] Margotin and Guesdon describe the musical performance as emitting "sorrow and fatalism".[143]

Artwork and packaging

[edit]The cover artwork of Nebraska is a black-and-white photograph of a black-top road under a cloudy sky taken through the windshield of a car.[30][38] The photograph was originally taken by the landscape photographer David Michael Kennedy during the winter of 1975.[38][144] Springsteen did not want himself on the cover, instead envisioning a landscape. Kennedy was hired by the art director Andrea Klein after showing Springsteen some of Kennedy's work. Kennedy provided various images before Springsteen selected the final one.[38][144] Some commentators have agreed that the artwork matches the album's tone and mood perfectly.[30][38][145] The singer's name and album title appear in bright red above and below the image, respectively, stylized in all caps.[38][146] Springsteen said of the image:[144]

"I liked the photograph [Klein] found and what was done with it, just the stark red-and-black, black-and-white layout, and the big letters. It was all just very bloody in its own way. I remember a lot of work, a lot of fussing over many of the album covers, but I don't remember Nebraska being one of them."

The back of the sleeve contains a photograph of Springsteen in a brightly lit room taken by Kennedy in his Brewster, New York, home.[38][146][145] Springsteen said he wanted his presence both known and unknown: "The picture we used inside, it was kind of my ghost. It wasn't quite me. It was ... the earlier part of yourself that stays with you."[146] The inside sleeve includes lyrics of the album's ten songs.[38] The album title was not chosen until shortly before the album's release. Nearly half of the song titles were considered, including State Trooper, Used Cars, and Reason to Believe, before Springsteen settled on Nebraska after the first song on the album and the first one he recorded.[147]

Release

[edit]What I thought and knew was that we could put this tape out and it would be a sensational record. ... I didn't know what would happen to it—how many people would hear it, what room there was for it on radio. ... After all, even if we had gotten the band on all the Nebraska material, nobody thought that this was the most commercial stuff Bruce had ever written. That was not one of the reactions anybody had.[148]

Columbia and its international arm CBS Records were ecstatic when Springsteen and Landau presented Nebraska to them. The labels' presidents, Walter Yetnikoff and Al Teller, respectively, believed the album would not sell as well as The River, but loved the music and felt it represented an artistic growth for Springsteen. Teller promised a more subdued advertising campaign compared to The River and anticipated sales of less than one million copies.[86]

Nebraska was released on September 30, 1982.[101][149] In a year dominated by British synth-pop,[150] the album stylistically stood apart from other releases in the year by artists such as A Flock of Seagulls, Lionel Richie, Olivia Newton-John, and the Human League.[151][14] It confused both casual and serious fans,[86] but sold well,[150] debuting on the U.S. Billboard Top LPs & Tape chart at number 29,[152] peaking at number three.[153] By 1989, it had sold one million copies and was certified platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA).[154] Elsewhere, the album peaked at number two in Sweden,[155] three in Canada,[156] Norway,[157] New Zealand,[158] and the U.K.,[159] seven in the Netherlands,[160] eight in Australia,[161] and ten in Japan.[162] It also reached number 18 in France and 37 in West Germany.[163][164]

Nebraska was supported by two singles. The first, "Atlantic City", with "Mansion on the Hill" as the B-side, was released in Europe and Japan only in October 1982.[125][165] Springsteen's first ever music video was produced as promotion for rotation on MTV. Directed by Arnold Levine, the "Atlantic City" video does not feature Springsteen himself, instead featuring black-and-white documentary-style footage of the titular city shot on location.[166] Commentators have described the video as "bleak" and "atmospheric".[167][142] "Open All Night" was released as the second single, again in Europe only, on November 22.[140] Its B-side was "The Big Payback", a rockabilly song with lyrics related to working life.[57]

Springsteen himself did not promote the album; he conducted no interviews and, for the first time after an album release, did not tour.[168][169][101] In his 2016 autobiography Born to Run, he explained that "it felt too soon after The River, and Nebraska's quiet stillness would take me a while longer to bring to the stage".[170] He also stated that he wanted listeners to experience the album for themselves: "I thought I could only hurt the project at that moment by trying to explain it ... if I could explain it."[171]

Following Nebraska's release, Springsteen vacationed on a cross-country road trip to California,[172] where he demoed new songs similar in style to Nebraska at his newly purchased Los Angeles home before returning to New York in April 1983 to continue recording with the E Street Band.[173][174][175] Sessions lasted until February 1984,[176] during which the band recorded between 70 and 90 songs.[177] The follow-up to Nebraska, Born in the U.S.A., was released in June 1984.[178] A rock and roll record,[179][180] it featured full-band arrangements of three songs from the original Colts Neck tape: "Born in the U.S.A.", "Downbound Train", and "Working on the Highway" (reworked from "Child Bride"), while the electric versions of "Pink Cadillac" and "Johnny Bye-Bye" were released as the B-sides of the "Dancing in the Dark" and "I'm on Fire" singles, respectively.[54][51][181] Out of the seventeen songs on the original demo tape, the crime tale "The Losin' Kind" is the only one that remains unreleased.[q][54][183]

Critical reception

[edit]| Initial reviews | |

|---|---|

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| Record Mirror | |

| Rolling Stone | |

| Smash Hits | 6½/10[109] |

| Sounds | |

| The Village Voice | A−[185] |

On its original release, critical reception to Nebraska was mostly positive.[150] It was hailed by critics for its boldness and individuality,[186] being called an unexpected,[109] brave,[96][111] and artistically daring record.[187] Its stylistic departure from Springsteen's previous works came as a shock to some critics.[96][184] Robert Hilburn compared the change in style to when Bob Dylan went electric,[186] and called Nebraska "one of the most bold uncompromising artistic statements since John Lennon's Plastic Ono Band album in 1970".[188]

Critics described Nebraska as Springsteen's most personal album up to that point;[r] the San Francisco Chronicle's Joel Selvin declared: "Never before has a major recording artist made himself so vulnerable or open."[187] In The New York Times, Robert Palmer summarized: "It's been a long time since a mainstream rock star made an album that asks such tough questions and refuses to settle for easy answers – let alone an album suggesting that perhaps there are no answers."[93] Rolling Stone's Steve Pond praised Nebraska as a "tactical masterstroke", positively comparing it to Darkness on the Edge of Town (1978), and commending Springsteen's "sharp focus" and "insistence on painting small details so clearly and his determination to make a folk album firmly in the tradition".[96] Trouser Press's Jon Young praised Springsteen's growth as an artist and felt he succeeded as a "guitar-strumming storyteller", saying: "He may have scaled down his attack, but Springsteen hasn't diminished his ambition one bit."[91]

Several commented on the acoustic instrumentation.[s] In Record Mirror, Mike Gardner felt that critics who believed Springsteen's power came solely from the E Street Band would be proven wrong, saying that "Springsteen's gift for making epic aural stories out of such material is turned on its head by the simple backing".[184] Writing for Sounds magazine, Johnny Waller enjoyed the "new perspective" gained from listening to the material in a back-to-basics approach.[103] Time magazine's Jay Cocks compared the sound to "a Library of Congress field recording made out behind some shutdown auto plant".[112] Cocks noticed a recycling of lyrical themes from older records, but felt they worked to Springsteen's advantage: "he can get the same sort of mythic resonance from this setting that John Ford took out of Monument Valley."[112] Commenting on the album's recording methods, The Boston Phoenix's Ariel Swartley said Nebraska is "the rock-and-roller's version of joining a monastery or running away to farm: solo, acoustic, old-fashioned, homemade."[122]

Other critics were more negative. Some felt that, due to similar music and themes, the songs stylistically merged together.[103][111] The Village Voice's Robert Christgau criticized the music, arguing that Springsteen lacked the vocal and melodic imagination to "enrich these bitter tales of late capitalism" with bare instrumentation.[185] More negatively, The Washington Post's Richard Harrington said Nebraska "may be the most undynamic album of 1982", panning the "horrid" and "flat" sound quality and concluding: "One applauds Springsteen's commitment, but questions its ponderous and portentous execution."[111] Musician magazine's Paul Nelson said the album sounded "demoralizing", "murderously monotonous", and "deprived of spark or hope", but in the end, he "found a road map that me to the right places".[189] In Smash Hits, David Hepworth felt that due to the album's dark tone and "bleak pessimism", it would likely only be appreciated by fans.[109][97] In Creem, Richard C. Walls enjoyed the album, but suspected that most listeners would find it "more admirable than likable".[190]

In The Village Voice's annual Pazz & Jop critics poll, Nebraska was voted the third best album of 1982, behind Elvis Costello's Imperial Bedroom and Richard and Linda Thompson's Shoot Out the Lights.[191] Rolling Stone included it in their list of the year's top 40 albums,[192] while NME placed it at number 33 in their end-of-year list.[193] Time included it in their list of the year's best albums.[194] In a 2022 list compiling the 50 best albums of 1982, Spin placed Nebraska at number 17.[195]

Legacy

[edit]Later records by Springsteen

[edit]In the decades following its release, Springsteen has released two albums in a similar stripped-down acoustic style of Nebraska: The Ghost of Tom Joad (1995) and Devils & Dust (2005).[43] With Ghost, Springsteen said that he wanted to "pick up where I'd left off with Nebraska, set the stories in the mid-'90s and in the land of my current residence, California".[196] With Devils, Springsteen felt that his acoustic demos were superior to full-band renditions.[197] Both albums contained downbeat themes, but unlike Nebraska, featured a handful of other musicians accompanying Springsteen on many tracks.[198] Many critics agree that the two albums failed to match the power and consistency of Nebraska.[13][43][95] Reflecting on Nebraska, Springsteen described it as his "most personal record": "It felt to me, in its tone, the most what my childhood felt like."[108] Speaking in 2023, Springsteen called it his definitive album.[199]

Retrospective reviews

[edit]| Retrospective reviews | |

|---|---|

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Chicago Tribune | |

| The Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| MusicHound Rock | 3.5/5[202] |

| New Musical Express | 7/10[203] |

| Pitchfork | 10/10[13] |

| Q | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| Tom Hull | B+[206] |

In later decades, Nebraska has been ranked as one of Springsteen's finest records.[t] Critics have called the record a masterpiece,[u] a classic,[210][211] one that enjoys repeated listens,[80] and one of the most brave albums ever released by a major artist.[14][4] Margotin and Guesdon said that with Nebraska, Springsteen elevated himself amongst the best singers in American popular music.[79] Bill See described Nebraska as "high art" on par with Guthrie, Steinbeck, and O'Connor.[14] It has been called an outlier in Springsteen's discography,[13][212][179] being released between the "stadium-rock" records The River and Born in the U.S.A.[80] It is also cited as the album non-Springsteen fans enjoy the most.[208][106]

Nebraska has been applauded for its storytelling,[80] themes, and production.[13] Martin Chilton and William Ruhlmann argue its unpolished nature and imperfections are a part of its charm.[30][4] Pitchfork's Mark Richardson said the songs are "very good", but "their true meaning came out in the presentation".[13] Sheeler commended Springsteen's ability to effectively weave himself as both narrator and character in the songs, wherein "the lines are blurred and each scene seems like a homespun conversation with each character" as they share their experiences.[104] Mojo's Sylvie Simmons said "that nakedness and willingness to face the darkness head-on that made Nebraska a touchstone for a whole new wave of young American bands."[213]

Nebraska may stand as Springsteen's most heroic moment. It may also be the album of his that will outlive the others, because of the timelessness of its style and its refusal to run away from the anguish of the human spirit.[186]

Several have described Nebraska as a timeless record,[94] having lost none of its power and its themes remaining relevant decades after its release.[105][214] Zanes argued the album's power was unveiled in the years following its initial release and listeners discovered it on their own time, being "passed around like a rumor".[215] Hyden similarly said that the album's stories of suffering can translate to "whatever era [listeners] happen to live in".[118] The Ringer's Elizabeth Nelson wrote that the stories of haunted highways and characters "still haunt the American psyche",[110] while The Daily Telegraph's Ian Winwood said the album remains Springsteen's "most enduring" record: "The hard truths behind its cold stare have proved persistent to the point of immovability."[214]

Not all reviews have been positive. Q magazine's Richard Williams believed that Nebraska would have been a better record with the E Street Band and "a few more months in the studio".[204] Consequence of Sound's Harry Houser and Bryan Kitching argue that due to its dark and heart-wrenching qualities, the stories were not easy-listening and lacked the ability to be played at parties or bars.[80]

Rankings

[edit]Nebraska has appeared on multiple best-of lists. In 1989, it was ranked 43rd on Rolling Stone magazine's list of the 100 greatest albums of the 1980s.[216] In 2003, it was ranked number 224 on Rolling Stone's list of the 500 greatest albums of all time,[216] 226 in a 2012 revised list,[217] and 150 in a 2020 reboot of the list.[218] In 2006, Q placed the album at number 13 in its list of "40 Best Albums of the '80s".[219] In 2012, Slant Magazine listed the album at number 57 on its list of "Best Albums of the 1980s".[220] The following year, NME ranked it number 148 in their list of the 500 greatest albums of all time.[221] Two years later, Ultimate Classic Rock included it in a list compiling the 100 best rock albums of the 1980s.[222] In 2018, Pitchfork listed it as the 28th greatest album of the 1980s.[100] In 2024, Paste magazine placed it at number 223 in their list of the 300 greatest albums of all time.[223] The album was also included in the book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die.[224]

Influence

[edit]Impact on home recording

[edit]Nebraska represented a breakthrough in home recording.[32][14][214] Spin magazine's Al Shipley wrote that at the time of its release, the majority of musical artists, including smaller indie bands, primarily only released music that was recorded in a studio and home demos were rarely made available to the public.[106] Nebraska has been credited as one of the first DIY records released by a major artist[14] and subsequently sparking a DIY revolution.[225] In the decades following its release, numerous artists began recording their own music at home.[14] Warren McQuiston wrote in Performer magazine: "The success of Nebraska strictly as a recording project was the "emperor has no clothes" moment. You could make a record at home, a real one that, and if done right could be good enough to be released on Colombia Records."[226]

Nebraska also influenced the indie rock and underground music scenes,[95][225] paving the way for releases by artists such as Ween, Neutral Milk Hotel, Iron & Wine, and Bon Iver.[226] Matt Berninger, lead singer of the National, said: "It wasn't just the fact that it was a magical record in terms of its scenes and characters. It was the idea that a major rock star could make something just in his bedroom. It exploded so many of my received ideas and told me that, maybe I could be a musician."[227] Nebraska is considered an essential home record,[v] the "most celebrated" lo-fi record by The Telegraph's Neil McCormick,[94] and was named the greatest home recording ever made by Paste magazine in 2012.[229]

Tributes

[edit]Numerous artists have paid tribute to Nebraska since its release. Johnny Cash covered "Johnny 99" and "Highway Patrolman" for his 1983 album Johnny 99.[230] A tribute album, Badlands: A Tribute to Bruce Springsteen's Nebraska, was released in 2000. Produced by Jim Sampas, it featured covers of the Nebraska songs recorded in a similar stripped-down spirit of the original recordings by artists including Cash, Hank Williams III, Los Lobos, Dar Williams, Deana Carter, Ani DiFranco, Son Volt, Ben Harper, Aimee Mann, and Michael Penn. The album also included covers of three other Springsteen tracks from the same period: "I'm on Fire", "Downbound Train", and "Wages of Sin".[211][231][232]

Other artists have discussed Nebraska's impact on their music. Rage Against the Machine's guitarist Tom Morello said: "I didn't know there was music like that, that was as impactful and as heavy as Nebraska was. The alienation that I felt was for the first time expressed in music, and then I became a huge superfan."[167] The singers Kelly Clarkson, Justin Vernon, and rock band the Killers cited Nebraska as an influence when making the albums My December (2007), For Emma, Forever Ago (2007), and Pressure Machine (2021), respectively.[233][234][235] The singer-songwriters Aoife O'Donovan and Ryan Adams released full track-by-track covers of Nebraska in 2020 and 2022, respectively.[236][237] O'Donovan performed the album live in its entirety several times throughout 2023.[238] Zach Bryan cited Nebraska as his favorite album ever written, and used it as the recording template for his first two albums, DeAnn (2019) and Elisabeth (2020), with an additional nod in the lyrics to the title track of The Great American Bar Scene (2024).[239] Nebraska was also a favorite of Richard Thompson, Rosanne Cash, and Steve Earle.[30][240]

Outside of music, "Highway Patrolman" provided the inspiration for the 1991 film The Indian Runner. Written and directed by Sean Penn and starring David Morse and Viggo Mortensen, the film follows the same plot outline as the song, telling the story of a troubled relationship between two brothers, a deputy sheriff and a criminal.[133][209] In literature, the short stories in Tennessee Jones's book Deliver Me from Nowhere (2005) were inspired by the themes of Nebraska. The book takes its title from a line in "Open All Night" and "State Trooper".[211] Another book, David Burke's Heart of Darkness: Bruce Springsteen's Nebraska (2011), analyzed the album's influence decades after its release,[14] while another, Warren Zanes's Deliver Me from Nowhere (2023), delved into the album's making, featuring interviews between Zanes and Springsteen.[241]

In media

[edit]Deliver Me from Nowhere film

[edit]A biographical film based on the making of Nebraska is in production at 20th Century Studios. Written and directed by Scott Cooper, the film, based on Warren Zanes's book Deliver Me from Nowhere (2023), follows Springsteen as he wrote and recorded the Nebraska songs, while dealing with the personal struggles of becoming a superstar. Titled Deliver Me from Nowhere, the film will star Jeremy Allen White as Springsteen, with Jeremy Strong, Odessa Young, Paul Walter Hauser, Harrison Gilbertson, Stephen Graham, and Johnny Cannizzaro in supporting roles. Springsteen and Jon Landau are both heavily involved in the project.[242][243][244] In an interview with NME, Strong named Nebraska his favorite Springsteen album and spoke about its influence on him: "It just always spoke to me, there's a melancholy to it. I am doing [Deliver Me From Nowhere] but I'd always felt that way about that album. There's a narrative to it that comes from a very deep place in him and you can feel that."[245] Filming began at the end of October 2024. The film is expected to be released in 2025.[246]

PBS special

[edit]A television special celebrating Nebraska, titled Bruce Springsteen's Nebraska: A Celebration in Words and Music, aired on PBS on August 31, 2024. The special, hosted by Zanes, was filmed in Nashville on September 19, 2023, and features numerous musicians singing the album's songs, including Emmylou Harris, Noah Kahan, and Lucinda Williams, interspersed with interviews from Zanes about the album's legacy. Zanes stated in a statement announcing the special: "I wrote a book about Nebraska because the recording stayed with me over decades. Every time there was trouble in my life I reached for Nebraska. When I started doing events around the book's publication, I quickly realized the best of them had music. When I went to Nashville, I had a remarkable cast of musicians to help me tell this story."[247][248]

Reissues

[edit]Nebraska was first released on CD in 1984.[157] This was followed by an LP and CD reissue by CBS in 1988.[160] Additional reissues followed in 2003 by Columbia and in 2008 by Sony BMG.[157] In 2015, Sony Music released a remastered version of the album on both LP and CD.[249][250] In October 2022, Sony Music reissued the album again on black smoke vinyl, featuring an original art print by Justin A. McHugh and a listening notes booklet with new sleeve notes by Springsteen biographer Peter Ames Carlin, to mark its 40th anniversary.[251]

Track listing

[edit]All tracks are written by Bruce Springsteen[1]

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Nebraska" | 4:27 |

| 2. | "Atlantic City" | 3:54 |

| 3. | "Mansion on the Hill" | 4:03 |

| 4. | "Johnny 99" | 3:38 |

| 5. | "Highway Patrolman" | 5:39 |

| 6. | "State Trooper" | 3:15 |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Used Cars" | 3:05 |

| 2. | "Open All Night" | 2:55 |

| 3. | "My Father's House" | 5:43 |

| 4. | "Reason to Believe" | 4:09 |

| Total length: | 41:02 | |

Personnel

[edit]According to the liner notes and the authors Philippe Margotin and Jean-Michel Guesdon:[1][41]

- Bruce Springsteen – vocals; guitars; harmonica (1–5, 7, 9–10); mandolin (1–3, 5); glockenspiel (1, 7); synthesizer (9)

- Mike Batlan – recording engineer

- Dennis King – mastering

- Bob Ludwig, Steve Marcussen – mastering consultants

- Andrea Klein – design

- David Michael Kennedy – photography (copyrighted 1975)

Charts

[edit]

Weekly charts[edit]

|

Year-end charts[edit]

|

Certifications

[edit]| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Australia (ARIA)[255] | Platinum | 70,000^ |

| Canada (Music Canada)[256] | Gold | 50,000^ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[257] | Gold | 100,000^ |

| United States (RIAA)[154] | Platinum | 1,000,000^ |

|

^ Shipments figures based on certification alone. | ||

Notes

[edit]- ^ Nebraska's LP sleeve does not list an official producer, instead crediting Mike Batlan as the recording engineer.[1] Speaking to Warren Zanes, Springsteen's manager, Jon Landau, explained that due to the album's "special way of coming into being", giving Springsteen a producer credit "didn't feel right to Bruce". Landau believed Springsteen was the only one worthy of the title but he "didn't take it for himself": "So there's no producer".[2] Other sources list Springsteen as the producer.[3][4]

- ^ Springsteen had recently performed Guthrie's "This Land Is Your Land" throughout the River Tour.[16]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[27][28][29][30]

- ^ Some commentators state the entire tape was recorded on January 3, 1982,[33][39][42][43][44] although others place the recording between December 17, 1981, and January 3, 1982.[45][46] According to Geoffrey Himes, Springsteen and Batlan "mixed the best songs from the new work the singer had been recording" on January 3.[47]

- ^ The boombox had fallen into a river while on a boating trip. The machine died but unexpectedly restarted a week later.[36]

- ^ "Bye Bye Johnny" was a Chuck Berry cover.[51] According to Clinton Heylin, it was the original "Johnny Bye-Bye" that appeared on the tape, which he believes was probably a live version from the River Tour rather than a recorded demo.[52]

- ^ Clinton Heylin states in the liner notes to the 2003 compilation album The Essential Bruce Springsteen that "The Big Payback" was recorded "shortly after" the Nebraska tape was completed.[56]

- ^ Springsteen and the E Street Band previously recorded The River at the Power Station.[60]

- ^ Originally titled "Come On (Let's Go Tonight)",[67] "Johnny Bye-Bye" was an Elvis Presley tribute that was a partial rewrite of Chuck Berry's "Bye Bye Johnny". Springsteen had debuted it during the River Tour.[68][69]

- ^ According to Zanes, Plotkin credits Landau with the idea of releasing the demos, Landau credits Springsteen, while Van Zandt believes it was his idea.[75] Dave Marsh also credits Landau.[76]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[78][79][80][81]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[80][104][101][95][105][106][107]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[108][109][110][111]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[93][123][124][121]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[93][101][120][130][131]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[93][139][140][141]

- ^ Springsteen taped a new version of "The Losin' Kind" during the 1983 Los Angeles home sessions, which also remains unreleased.[182]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[93][97][102][187]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[96][102][103][112][109]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[94][101][207][115][208][209][106][105]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[14][30][94][110]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[13][94][212][228]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Nebraska (liner notes). Bruce Springsteen. US: Columbia Records. 1982. TC 38358.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Zanes 2023, p. 198.

- ^ Gaar 2016, p. 198.

- ^ a b c d e f Ruhlmann, William. "Nebraska – Bruce Springsteen". AllMusic. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- ^ Lifton, Dave (October 17, 2015). "When Bruce Springsteen's 'The River' Became His First No. 1 Album". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on November 30, 2023. Retrieved February 12, 2024.

- ^ Zanes 2023, pp. 70–71.

- ^ a b Zanes 2023, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Zanes 2023, p. 83.

- ^ Gaar 2016, p. 80.

- ^ Margotin & Guesdon 2020, p. 222.

- ^ Zanes 2023, p. 85.

- ^ Carlin 2012, p. 285.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Richardson, Mark. "Bruce Springsteen: Nebraska Album Review". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on March 24, 2018. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p See, Bill (February 5, 2012). "'Nebraska': Bruce Springsteen's 'Heart of Darkness'". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on May 13, 2024. Retrieved May 13, 2024.

- ^ a b Springsteen 2003, p. 136.

- ^ Hyden 2024, p. 78.

- ^ Margotin & Guesdon 2020, pp. 190, 192.

- ^ a b c d Streight, Irwin (2008). "The Ghost of Flannery O'Connor in the Songs of Bruce Springsteen". Flannery O'Connor Review. 6: 11–29. ISSN 2687-8267. Archived from the original on August 17, 2024. Retrieved August 17, 2024.

- ^ Marsh 1987, p. 97.

- ^ Marsh 1987, p. 94.

- ^ Himes 2005, p. 61.

- ^ Kirkpatrick 2007, p. 84.

- ^ a b Springsteen 2003, p. 138.

- ^ Kirkpatrick 2007, p. 83.

- ^ Carlin 2012, pp. 291–293.

- ^ Himes 2005, p. 11.

- ^ Dolan 2012, p. 190.

- ^ Springsteen 2016, p. 299.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Nebraska by Bruce Springsteen". Classic Rock Review. April 15, 2012. Archived from the original on September 21, 2024. Retrieved May 13, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Chilton, Martin (January 5, 2012). "Heart Of Darkness: Bruce Springsteen's Nebraska by David Burke, review". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on May 13, 2024. Retrieved May 13, 2024.

- ^ Zanes 2023, p. 150.

- ^ a b Zanes 2023, p. 19.

- ^ a b Dolan 2012, pp. 190–191.

- ^ Margotin & Guesdon 2020, p. 192.

- ^ Kirkpatrick 2007, pp. 81–82.

- ^ a b Carlin 2012, p. 293.

- ^ Zanes 2023, p. 145.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Margotin & Guesdon 2020, p. 194.

- ^ a b Zanes 2023, p. 151.

- ^ Zanes 2023, p. 156.

- ^ a b Margotin & Guesdon 2020, pp. 198–217.

- ^ a b c d Carlin 2012, p. 294.

- ^ a b c d e Lifton, Dave (January 3, 2016). "How One Amazing Night Led to Bruce Springsteen's 'Nebraska'". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on June 4, 2024. Retrieved September 22, 2024.

- ^ Sandford 1999, p. 193.

- ^ a b c d e Margotin & Guesdon 2020, p. 195.

- ^ a b Heylin 2012, p. 309.

- ^ Himes 2005, p. 26.

- ^ a b Dolan 2012, p. 191.

- ^ Zanes 2023, pp. 155–158.

- ^ Springsteen 2003, p. 135.

- ^ a b Kirkpatrick 2007, pp. 102, 104.

- ^ Heylin 2013, pp. 242–243.

- ^ a b Zanes 2023, pp. 164–166.

- ^ a b c d Himes 2005, p. 27.

- ^ a b Kirkpatrick 2007, p. 82.

- ^ Heylin 2012, p. 484.

- ^ a b Margotin & Guesdon 2020, pp. 218–219.

- ^ a b c d e Margotin & Guesdon 2020, p. 216.

- ^ Heylin 2012, p. 490.

- ^ Gaar 2016, pp. 74–80.

- ^ Zanes 2023, p. 168.

- ^ a b Himes 2005, p. 31.

- ^ Marsh 1987, pp. 113–115.

- ^ Dolan 2012, p. 196.

- ^ Zanes 2023, pp. 173–174.

- ^ Carlin 2012, p. 295.

- ^ Margotin & Guesdon 2020, p. 259.

- ^ Heylin 2013, pp. 220, 222.

- ^ Hyden 2024, p. 12.

- ^ Zanes 2023, pp. 169–171.

- ^ Himes 2005, p. 49.

- ^ Marsh 1987, pp. 115–118.

- ^ a b Margotin & Guesdon 2020, p. 196.

- ^ Heylin 2013, p. 257.

- ^ Zanes 2023, pp. 176–179.

- ^ Marsh 1987, pp. 119–120.

- ^ Himes 2005, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Gaar 2016, p. 82.

- ^ a b c d e Margotin & Guesdon 2020, pp. 192–193.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hauser, Henry; Kitching, Bryan (July 20, 2013). "Dusting 'Em Off: Bruce Springsteen – Nebraska". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on April 26, 2017. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- ^ a b Zanes 2023, p. 185.

- ^ Hyden 2024, p. 80.

- ^ Loder, Kurt (December 6, 1984). "The Rolling Stone Interview: Bruce Springsteen". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on May 5, 2024. Retrieved May 13, 2024.

- ^ "The Rock Radio: Springsteen looking at archival releases". The Rock Radio. July 31, 2006. Archived from the original on March 12, 2007.

- ^ Greene, Andy (June 10, 2010). "Max Weinberg on His Future With Conan and Bruce". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on June 13, 2010. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- ^ a b c Carlin 2012, p. 296.

- ^ Zanes 2023, pp. 192–194.

- ^ Heylin 2013, p. 258.

- ^ Keller, Daniel (July 25, 2007). "Bruce Springsteen's "Nebraska" – A PortaStudio, two SM57's, and Inspiration". Tascam. Archived from the original on May 1, 2024. Retrieved August 14, 2024.

- ^ Springsteen 2003, pp. 138–139.

- ^ a b Young, Jon (January 1983). "Bruce Springsteen: Nebraska (Columbia)". Trouser Press. Archived from the original on September 21, 2024. Retrieved April 30, 2023 – via Rock's Backpages.

- ^ Margotin & Guesdon 2020, pp. 142–144.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Palmer, Robert (September 26, 1982). "Bruce Springsteen Fashions a Compelling, Austere Message". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 30, 2023. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g McCormick, Neil (October 24, 2020). "Bruce Springsteen: all his albums ranked, from worst to best". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on August 23, 2023. Retrieved November 14, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Pelone, Joe (April 3, 2012). "Bruce Springsteen – Nebraska". Punk News. Archived from the original on May 13, 2024. Retrieved September 22, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Pond, Steve (October 28, 1982). "Nebraska". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on July 26, 2013. Retrieved May 12, 2013.

- ^ a b c "Top Album Picks" (PDF). Billboard. October 2, 1982. p. 62. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 21, 2024. Retrieved April 11, 2024 – via worldradiohistory.com.

- ^ Marsh 1987, pp. 128–129.

- ^ Pareles, Jon (August 30, 1987). "Heartland Rock: Bruce's Children". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 22, 2016. Retrieved December 22, 2016.

- ^ a b Pitchfork Staff (September 10, 2018). "The 200 Best Albums of the 1980s". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on February 22, 2024. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k McLaughlin, David (October 1, 2022). "How Bruce Springsteen battled the "black sludge" of depression to make his brutal, lo-fi masterpiece Nebraska". Louder. Archived from the original on May 13, 2024. Retrieved May 13, 2024.

- ^ a b c "Album Reviews: Out of the Box" (PDF). Cash Box. October 2, 1982. p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 13, 2024. Retrieved April 11, 2024 – via worldradiohistory.com.

- ^ a b c d e f Waller, Johnny (September 25, 1982). "Bruce on the loose...". Sounds. p. 33.

- ^ a b c Sheeler, Ryan (2007). "A Meanness in This World: The American Outlaw as Storyteller in Bruce Springsteen's Nebraska". American Studies Journal (50). doi:10.18422/50-8. Archived from the original on August 17, 2024. Retrieved August 17, 2024.

- ^ a b c Lifton, Dave (July 29, 2015). "Bruce Springsteen Albums Ranked Worst to Best". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Shipley, Al (November 11, 2022). "Every Bruce Springsteen Album, Ranked". Spin. Archived from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- ^ Hyden 2024, p. 76.

- ^ a b Sandford 1999, p. 197.

- ^ a b c d e Hepworth, David (September 30 – October 13, 1982). "Bruce Springsteen: Nebraska". Smash Hits. 2 (21): 25.

- ^ a b c d Nelson, Elizabeth (December 14, 2022). "Please Don't Stop Me: 40 Years of Bruce Springsteen's 'Nebraska'". The Ringer. Archived from the original on May 13, 2024. Retrieved May 13, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Harrington, Richard (October 2, 1982). "Springsteen, Hounded by the Blight". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 20, 2024. Retrieved November 20, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Cocks, Jay (November 15, 1982). "Music: Against the American Grain". Time. Archived from the original on November 20, 2024. Retrieved November 20, 2024.

- ^ a b DeGagne, Mike. "'Atlantic City' – Bruce Springsteen". AllMusic. Archived from the original on May 13, 2024. Retrieved May 13, 2024.

- ^ a b c Ruhlmann, William. "'Reason to Believe' – Bruce Springsteen". AllMusic. Archived from the original on May 13, 2024. Retrieved May 13, 2024.

- ^ a b Hann, Michael (May 30, 2019). "Bruce Springsteen's albums – ranked!". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 31, 2023. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- ^ Marsh 2004, p. 378.

- ^ Hyden 2024, p. 73.

- ^ a b Hyden 2024, p. 74.

- ^ Hilburn 1985, p. 176.

- ^ a b c Ruhlmann, William. "'Johnny 99' – Bruce Springsteen". AllMusic. Archived from the original on May 13, 2024. Retrieved May 13, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Kirkpatrick 2007, p. 86.

- ^ a b Swartley, Ariel (October 5, 1982). "The loneliness of the long-distance driver – Bruce Springsteen: blood and darkness and diesel fumes". The Boston Phoenix. Vol. 11, no. 40. pp. 6, 10. Retrieved November 6, 2024.

- ^ Dolan 2012, p. 188.

- ^ a b c Margotin & Guesdon 2020, p. 198.

- ^ a b c Margotin & Guesdon 2020, pp. 201–202.

- ^ Kirkpatrick 2007, p. 87.

- ^ a b c Margotin & Guesdon 2020, pp. 204–205.

- ^ a b c d Kirkpatrick 2007, p. 85.

- ^ Ward, Thomas. "'Mansion on the Hill' – Bruce Springsteen". AllMusic. Archived from the original on May 13, 2024. Retrieved May 13, 2024.

- ^ a b Margotin & Guesdon 2020, pp. 206–207.

- ^ a b Kirkpatrick 2007, pp. 86–87.

- ^ a b Ward, Thomas. "'Highway Patrolman' – Bruce Springsteen". AllMusic. Archived from the original on May 13, 2024. Retrieved May 13, 2024.

- ^ a b Margotin & Guesdon 2020, pp. 208–209.

- ^ a b c Margotin & Guesdon 2020, pp. 210–211.

- ^ a b c Kirkpatrick 2007, p. 88.

- ^ Ward, Thomas. "'State Trooper' – Bruce Springsteen". AllMusic. Archived from the original on May 13, 2024. Retrieved May 13, 2024.

- ^ Margotin & Guesdon 2020, p. 212.

- ^ Ward, Thomas. "'Used Cars' – Bruce Springsteen". AllMusic. Archived from the original on September 21, 2024. Retrieved May 13, 2024.

- ^ a b Ward, Thomas. "'Open All Night' – Bruce Springsteen". AllMusic. Archived from the original on May 13, 2024. Retrieved May 13, 2024.

- ^ a b c Margotin & Guesdon 2020, pp. 214–215.

- ^ a b c Kirkpatrick 2007, p. 90.

- ^ a b Kirkpatrick 2007, p. 91.

- ^ Margotin & Guesdon 2020, p. 217.

- ^ a b c Zanes 2023, p. 215.

- ^ a b Marsh 1987, pp. 140–141.

- ^ a b c Zanes 2023, pp. 215–216.

- ^ Marsh 1987, p. 141.

- ^ Marsh 1987, p. 142.

- ^ Zanes 2023, p. 227.

- ^ a b c Marsh 1987, p. 144.

- ^ Zanes 2023, p. 220.

- ^ Margotin & Guesdon 2020, p. 193.

- ^ a b "Bruce Springsteen Chart History: Billboard 200". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 17, 2021. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ^ a b "American album certifications – Bruce Springsteen – Nebraska". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved September 7, 2024.

- ^ a b "Swedishcharts.com – Bruce Springsteen – Nebraska". Hung Medien. Retrieved April 11, 2024.

- ^ a b "Top Albums/CDs". RPM. Vol. 37, no. 13. Library and Archives Canada. November 13, 1982. Archived from the original on January 5, 2016. Retrieved April 4, 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Norwegiancharts.com – Bruce Springsteen – Nebraska". Hung Medien. Retrieved April 11, 2024.

- ^ a b "Charts.nz – Bruce Springsteen – Nebraska". Hung Medien. Retrieved April 11, 2024.

- ^ a b "The Official Charts Company: Bruce Springsteen – Nebraska" (PHP). UK Albums Chart. Archived from the original on April 5, 2015. Retrieved April 4, 2012.

- ^ a b c "Dutchcharts.nl – Bruce Springsteen – Nebraska" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved April 11, 2024.

- ^ a b Kent 1993, p. 289.

- ^ a b Oricon Album Chart Book: Complete Edition 1970-2005. Roppongi, Tokyo: Oricon Entertainment. 2006. ISBN 4-87131-077-9.

- ^ a b "InfoDisc : Tous les Albums classés par Artiste > Choisir Un Artiste Dans la Liste" (in French). infodisc.fr. Archived from the original on May 6, 2013. Retrieved April 4, 2012.Note: user must select 'Bruce SPRINGSTEEN' from drop-down

- ^ a b "Album Search: Bruce Springsteen – Nebraska" (in German). Media Control. Archived from the original on December 5, 2013. Retrieved October 31, 2011.

- ^ Strong 1995, p. 773.

- ^ Zanes 2023, pp. 216–219.

- ^ a b Carlin 2012, p. 297.

- ^ Zanes 2023, pp. 223–224.

- ^ Himes 2005, p. 88.

- ^ Springsteen 2016, p. 301.

- ^ Zanes 2023, p. 225.

- ^ Carlin 2012, pp. 298–299.

- ^ Margotin & Guesdon 2020, p. 227.

- ^ Dolan 2012, pp. 199–201.

- ^ Heylin 2013, pp. 261–264.

- ^ Margotin & Guesdon 2020, pp. 228–229.

- ^ Kirkpatrick 2007, p. 102.

- ^ Gaar 2016, p. 88.

- ^ a b Hyden 2024, p. 89.

- ^ Holden, Stephen (May 27, 1984). "Springsteen Scans the American Dream". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 11, 2021. Retrieved February 12, 2024.

- ^ Zanes 2023, p. 171.

- ^ Heylin 2013, p. 264.

- ^ Carlin 2012, p. 292.

- ^ a b c Gardner, Mike (September 25, 1982). "Boss sacks workers (shock)" (PDF). Record Mirror. p. 23. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 20, 2024. Retrieved April 11, 2024.

- ^ a b Christgau, Robert (November 30, 1982). "Christgau's Consumer Guide". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on September 14, 2015. Retrieved September 6, 2015.

- ^ a b c Hilburn 1985, p. 168.

- ^ a b c Selvin, Joel (October 17, 1982). "Bruce Springsteen: Nebraska (Columbia 38358)". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on April 30, 2023. Retrieved April 30, 2023 – via Rock's Backpages.

- ^ Hilburn, Robert (June 3, 1984). "Springsteen Stills Blows Them Away". Los Angeles Times. p. 57. Archived from the original on May 10, 2024. Retrieved April 16, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Heylin 2013, p. 260: Paul Nelson, Musician

- ^ Heylin 2013, p. 260: Richard C. Walls, Creem

- ^ "The 1982 Pazz & Jop Critics Poll". The Village Voice. February 23, 1983. Archived from the original on August 10, 2020. Retrieved December 3, 2016.

- ^ "The Top Forty Albums". Rolling Stone. No. 385. December 23, 1982. p. 105.

- ^ "NME's best albums and tracks of 1982". NME. October 10, 2016. Archived from the original on September 7, 2024. Retrieved May 13, 2024.

- ^ "Music: The Best of 1982". Time. January 3, 1983. Archived from the original on November 20, 2024. Retrieved November 20, 2024.

- ^ "The 50 Best Albums of 1982". Spin. August 15, 2022. Archived from the original on April 17, 2024. Retrieved October 31, 2024.

- ^ Springsteen 2016, p. 401.

- ^ Springsteen 2016, p. 444.

- ^ Margotin & Guesdon 2020, pp. 370, 458.

- ^ Kaufman, Gil (April 28, 2023). "Bruce Springsteen Says 'Nebraska' Is His Most Definitive Album". Billboard. Archived from the original on September 21, 2024. Retrieved May 13, 2024.

- ^ Kot, Greg (August 23, 1992). "The Recorded History of Springsteen". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ^ Larkin 2011, p. 1,957.

- ^ Graff 1996, pp. 638–639.

- ^ Bailie, Stuart; Staunton, Terry (March 11, 1995). "Ace of boss". New Musical Express. pp. 54–55.

- ^ a b Williams, Richard (December 1989). "All or Nothing: The Springsteen back catalogue". Q. No. 39. p. 149. Archived from the original on February 12, 2024. Retrieved February 12, 2024 – via Rock's Backpages.

- ^ Sheffield, Rob; et al. (2004). Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). Simon and Schuster. pp. 771–2. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- ^ Hull, Tom (October 29, 2016). "Streamnotes (October 2016)". Tom Hull – on the Web. Archived from the original on July 4, 2020. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- ^ "Readers' Poll: Ten Favorite Bruce Springsteen Albums". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ a b Hyden, Steven (November 11, 2022). "Every Bruce Springsteen Studio Album, Ranked". Uproxx. Archived from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- ^ a b Taub, Matthew (November 8, 2022). "Bruce Springsteen: every album ranked in order of greatness". NME. Archived from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- ^ Sandford 1999, p. 195.

- ^ a b c Kirkpatrick 2007, p. 81.

- ^ a b Embley, Jochan (March 26, 2020). "Five classic albums recorded during self-isolation: From Bon Iver to Bruce Springsteen". The Standard. Archived from the original on October 6, 2024. Retrieved October 5, 2024.

- ^ Simmons, Sylvie (January 2006). "Nebraska". Mojo. No. 146.

- ^ a b c Winwood, Ian (October 21, 2022). "Nebraska at 40: Bruce Springsteen's American nightmare". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on May 13, 2024. Retrieved May 13, 2024.

- ^ Zanes 2023, p. 14.

- ^ a b "100 Best Albums of the Eighties". Rolling Stone. November 16, 1989. Archived from the original on February 19, 2014. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. 2012. Archived from the original on July 6, 2019. Retrieved September 16, 2019.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. September 22, 2020. Archived from the original on September 22, 2020. Retrieved September 21, 2021.

- ^ "The 40 Best Albums of the '80s". Q. No. 241. August 2006.

- ^ "The 100 Best Albums of the 1980s". Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on March 14, 2012. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- ^ Barker, Emily (October 25, 2013). "The 500 Greatest Albums Of All Time: 200–101". NME. Archived from the original on November 8, 2023. Retrieved October 6, 2024.

- ^ "Top 100 '80s Rock Albums". Ultimate Classic Rock. July 12, 2015. Archived from the original on September 4, 2024. Retrieved October 6, 2024.

- ^ Paste Staff (June 3, 2024). "The 300 Greatest Albums of All Time". Paste. Archived from the original on September 17, 2024. Retrieved September 23, 2024.

- ^ Dimery & Lydon 2006, p. 499.

- ^ a b Zanes 2023, p. 16.

- ^ a b McQuiston, Warren (August 28, 2015). "How Bruce Springsteen's Nebraska Sparked a Home Recording Revolution". Performer. Archived from the original on September 21, 2024. Retrieved August 15, 2024.

- ^ Zanes 2023, p. 15.

- ^ Terich, Jeff (April 21, 2020). "10 Essential Home-Recorded Albums". Treble. Archived from the original on September 5, 2024. Retrieved October 6, 2024.

- ^ Kane, Tyler (January 17, 2012). "10 Great Albums Recorded at Home". Paste. Archived from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved September 23, 2024.

- ^ Worbois, Jim. "Johnny 99 – Johnny Cash". AllMusic. Archived from the original on September 23, 2024. Retrieved September 23, 2024.

- ^ Unterberger, Richie. "Badlands: A Tribute To Bruce Springsteen's Nebraska – Various Artists". AllMusic. Archived from the original on May 29, 2013. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- ^ Hess, Christopher (December 29, 2000). "Review: Badlands: A Tribute to Bruce Springsteen's 'Nebraska'". The Austin Chronicle. Archived from the original on May 13, 2024. Retrieved August 15, 2024.

- ^ Sheffield, Rob (July 2, 2007). "My December". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on July 29, 2016. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ Hyden, Steven (February 21, 2008). "Justin Vernon of Bon Iver". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on June 4, 2024. Retrieved October 5, 2024.

- ^ Baltin, Steve (August 8, 2021). "Sunday Conversation: The Killers On Their Intimate And Different New Album, Supergroups And Literature". Forbes. Archived from the original on October 27, 2021. Retrieved October 27, 2021.

- ^ Schisgall, Elias (July 26, 2023). "Aoife O'Donovan Channels Springsteen". The Provincetown Independent. Archived from the original on May 26, 2024. Retrieved September 23, 2024.

- ^ Laing, Rob (November 24, 2022). "Ryan Adams has covered the whole of Bruce Springsteen's Nebraska album and he's giving it away". Music Radar. Archived from the original on July 12, 2024. Retrieved September 23, 2024.

- ^ Boyle, Fionnuala (December 6, 2023). "Irish American singer Aoife O'Donovan will cover Bruce Springsteen's album Nebraska at Philadelphia show". Irish Star. Archived from the original on September 23, 2024. Retrieved September 23, 2024.

- ^ Hiatt, Brian (October 16, 2024). "Zach Bryan Meets Bruce Springsteen: 'I Never Thought I'd Be Sitting Here With You'". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on November 17, 2024. Retrieved October 23, 2024.

- ^ Zanes 2023, pp. 236, 238.

- ^ Chianca, Peter (May 31, 2023). "Review: Zanes delivers on 'Deliver Me From Nowhere', a history of Springsteen's 'Nebraska'". Boston.com. Archived from the original on September 23, 2023. Retrieved October 23, 2024.

- ^ Carey, Emma (January 13, 2024). "Bruce Springsteen Developing Nebraska Feature Film: Report". Consequence. Archived from the original on January 26, 2024. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ Cordero, Rosy (October 17, 2024). "Johnny Cannizzaro To Play Stevie Van Zandt In Bruce Springsteen Biopic 'Deliver Me From Nowhere'". Deadline. Retrieved October 21, 2024.

- ^ Shanfeld, Ethan (September 27, 2024). "Stephen Graham to Play Bruce Springsteen's Dad in Jeremy Allen White Movie 'Deliver Me From Nowhere'". Variety. Archived from the original on October 29, 2024. Retrieved October 21, 2024.

- ^ Flood, Alex (October 18, 2024). "Jeremy Strong confirms Springsteen biopic casting and reveals favourite album". NME. Archived from the original on November 15, 2024. Retrieved October 21, 2024.

- ^ Shafer, Ellise (October 28, 2024). "Jeremy Allen White Is the Boss in First Look at Bruce Springsteen Biopic 'Deliver Me From Nowhere'". Variety. Archived from the original on November 20, 2024. Retrieved October 28, 2024.

- ^ Kaufman, Gil (August 14, 2024). "Bruce Springsteen 'Nebraska: A Celebration of Words and Music' PBS Special Trailer Features Noah Kahan, Emmylou Harris, Eric Church". Yahoo!. Archived from the original on August 14, 2024. Retrieved August 14, 2024.

- ^ Gallucci, Michael (August 14, 2024). "Bruce Springsteen 'Nebraska' Tribute Coming to PBS". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on August 14, 2024. Retrieved August 14, 2024.

- ^ Ruhlmann, William. "Nebraska [LP] – Bruce Springsteen". AllMusic. Archived from the original on October 7, 2024. Retrieved October 6, 2024.

- ^ Ruhlmann, William. "Nebraska [CD] – Bruce Springsteen". AllMusic. Archived from the original on October 7, 2024. Retrieved October 6, 2024.

- ^ Fu, Eddie (September 15, 2022). "Bruce Springsteen's Nebraska Gets 40th Anniversary Vinyl Reissue". Consequence. Retrieved October 6, 2024.

- ^ "Swisscharts.com – Bruce Springsteen – Nebraska". Hung Medien. Retrieved April 11, 2024.

- ^ "Top 100 Albums '82". RPM. December 25, 1982. Archived from the original on July 29, 2012. Retrieved March 3, 2012.

- ^ "Complete UK Year-End Album Charts". Archived from the original on May 19, 2012. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ^ "ARIA Charts – Accreditations – 2008 Albums" (PDF). Australian Recording Industry Association. Retrieved April 4, 2012.

- ^ "Canadian album certifications – Bruce Springsteen – Nebraska". Music Canada. Retrieved April 4, 2012.

- ^ "British album certifications – Bruce Springsteen – Nebraska". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved April 4, 2012.

Sources

[edit]- Carlin, Peter Ames (2012). Bruce. New York City: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4391-9182-8.

- Dimery, Robert; Lydon, Michael (2006). 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die (Revised and Updated ed.). New York City: Universe. ISBN 978-0-7893-1371-3.

- Dolan, Marc (2012). Bruce Springsteen and the Promise of Rock 'n' Roll. New York City: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-39308-135-0.

- Gaar, Gillian G. (2016). Boss: Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band – The Illustrated History. Minneapolis: Voyageur Press. ISBN 978-0-76034-972-4.

- Graff, Gary (1996). "Bruce Springsteen". In Graff, Gary (ed.). MusicHound Rock: The Essential Album Guide. Detroit: Visible Ink Press. ISBN 978-0-7876-1037-1.

- Heylin, Clinton (2012). E Street Shuffle: The Glory Days of Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band (2013 ed.). London: Constable. ISBN 978-1-78033-868-2.

- Heylin, Clinton (2013). E Street Shuffle: The Glory Days of Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band (First American ed.). New York City: Viking Press. ISBN 978-0-670-02662-3.

- Hilburn, Robert (1985). Springsteen. New York City: Scribner. ISBN 978-0-684-18456-2.

- Himes, Geoffrey (2005). Bruce Springsteen's Born in the U.S.A. London: Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-0-8264-1661-2. Archived from the original on May 10, 2024. Retrieved May 13, 2024.

- Hyden, Steven (2024). There Was Nothing You Could Do: Bruce Springsteen's "Born in the U.S.A." and the End of the Heartland. New York City: Hachette Books. ISBN 978-0-306-83206-2.

- Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992 (illustrated ed.). St Ives: Australian Chart Book. ISBN 978-0-646-11917-5.

- Kirkpatrick, Rob (2007). The Words and Music of Bruce Springsteen. Santa Barbara: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-27598-938-5.

- Larkin, Colin (2011). "Bruce Springsteen". The Encyclopedia of Popular Music (5th ed.). London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-85712-595-8.

- Margotin, Philippe; Guesdon, Jean-Michel (2020). Bruce Springsteen All the Songs: The Story Behind Every Track. London: Cassell Illustrated. ISBN 978-1-78472-649-2. Archived from the original on February 26, 2023. Retrieved April 11, 2024.

- Marsh, Dave (1987). Glory Days: Bruce Springsteen in the 1980s. New York City: Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0-394-54668-1.

- Marsh, Dave (2004). Bruce Springsteen: Two Hearts – The Definitive Biography, 1972–2003. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-96928-4.

- Sandford, Christopher (1999). Springsteen: Point Blank. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-31664-845-5.

- Springsteen, Bruce (2016). Born to Run. New York City: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-5011-4151-5.

- Springsteen, Bruce (2003). Songs. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-0-7535-0862-6.

- Strong, Martin (1995). Great Rock Discography. Edinburgh: Canongate Press. ISBN 978-0-86241-541-9.

- Zanes, Warren (2023). Deliver Me From Nowhere: The Making of Bruce Springsteen's Nebraska. New York City: Crown. ISBN 978-0-59323-741-0. Archived from the original on May 10, 2024. Retrieved April 11, 2024.

External links

[edit]- Nebraska at Discogs (list of releases)

- Album lyrics and audio samples