Capital (architecture)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2007) |

In architecture, the capital (from Latin caput 'head') or chapiter forms the topmost member of a column (or a pilaster). It mediates between the column and the load thrusting down upon it, broadening the area of the column's supporting surface. The capital, projecting on each side as it rises to support the abacus, joins the usually square abacus and the usually circular shaft of the column. The capital may be convex, as in the Doric order; concave, as in the inverted bell of the Corinthian order; or scrolling out, as in the Ionic order. These form the three principal types on which all capitals in the classical tradition are based.

The Composite order was formalized in the 16th century following Roman Imperial examples such as the Arch of Titus in Rome. It adds Ionic volutes to Corinthian acanthus leaves.

From the highly visible position it occupies in all colonnaded monumental buildings, the capital is often selected for ornamentation; and is often the clearest indicator of the architectural order. The treatment of its detail may be an indication of the building's date.

Capitals occur in many styles of architecture, before and after the classical architecture in which they are so prominent.

Pre-classical Antiquity

[edit]Egyptian

[edit]The two earliest Egyptian capitals of importance are those based on the lotus and papyrus plants respectively, and these, with the palm tree capital, were the chief types employed by the Egyptians, until under the Ptolemies in the 3rd to 1st centuries BC, various other river plants were also employed, and the conventional lotus capital went through various modifications.

Many motifs of Egyptian ornamentation are symbolic, such as the scarab, or sacred beetle, the solar disk, and the vulture. Other common motifs include palm leaves, the papyrus plant, and the buds and flowers of the lotus.[1]

Some of the most popular types of capitals were the Hathor, lotus, papyrus and Egyptian composite. Most of the types are based on vegetal motifs. Capitals of some columns were painted in bright colors.

-

Illustration of papyriform capitals, in The Grammar of Ornament, 1856

-

Nine types of capitals, from The Grammar of Ornament

-

Egyptian composite columns from Philae

-

Papyriform columns in the Luxor Temple

-

Composite papyrus capital; 380-343 BC; painted sandstone; height: 126 cm (495⁄8 in.); Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Fragments of a palm column; 2353-2323 BC; granite; diameter beneath the ropes of the neck 80.85 cm (3113⁄16 in.); Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Model of a quatrefoil palmette capital; 400-30 BC; limestone; height: 23.9 cm (97⁄16 in.); Metropolitan Museum of Art

Assyrian

[edit]Some kind of volute capital is shown in the Assyrian bas-reliefs, but no Assyrian capital has ever been found; the enriched bases exhibited in the British Museum were initially misinterpreted as capitals.

Persian

[edit]In the Achaemenid Persian capital, the brackets are carved with two heavily decorated back-to-back animals projecting right and left to support the architrave; on their backs they carry other brackets at right angles to support the cross timbers. The bull is the most common, but there are also lions and griffins. The capital extends below for further than in most other styles, with decoration drawn from the many cultures that the Persian Empire conquered including Egypt, Babylon, and Lydia. There are double volutes at the top and, inverted, bottom of a long plain fluted section which is square, although the shaft of the column is round, and also fluted.

Aegean

[edit]The earliest Aegean capital is that shown in the frescoes at Knossos in Crete (1600 BC); it was of the convex type, probably moulded in stucco. Capitals of the second, concave type, include the richly carved examples of the columns flanking the Tomb of Agamemnon in Mycenae (c. 1100 BC): they are carved with a chevron device, and with a concave apophyge on which the buds of some flowers are sculpted.

Proto-Aeolic

[edit]Volute capitals, also known as proto-Aeolic capitals, are encountered in Iron-Age Southern Levant and ancient Cyprus, many of them in royal architectural contexts in the kingdoms of Israel and Judah starting from the 9th century BCE, as well as in Moab, Ammon, and at Cypriot sites such as the city-state of Tamassos in the Archaic period.[2][3]

Classical Antiquity

[edit]

The orders, structural systems for organising component parts, played a crucial role in the Greeks' search for perfection of ratio and proportion. The Greeks and Romans distinguished three classical orders of architecture, the Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian orders; each had different types of capitals atop the columns of their hypostyle and trabeate monumental buildings. Throughout the Mediterranean Basin, the Near East, and the wider Hellenistic world including the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom and the Indo-Greek Kingdom, numerous variations on these and other designs of capitals co-existed with the regular classical orders. The only architectural treatise of classical antiquity to survive is De architectura by the 1st-century BC Roman architect Vitruvius, who discussed the different proportions of each of these orders and made recommendations for how the column capitals of each order were to be constructed and in what proportions. In the Roman world and within the Roman Empire, the Tuscan order was employed, originally from Italy and with a capital similar to Greek Doric capitals, while the Roman imperial period saw the emergence of the Composite order, with a hybrid capital developed from Ionic and Corinthian elements. The Tuscan and Corinthian columns were counted among the classical canon of orders by the architects of Renaissance architecture and Neoclassical architecture.

Greek

[edit]Doric

[edit]

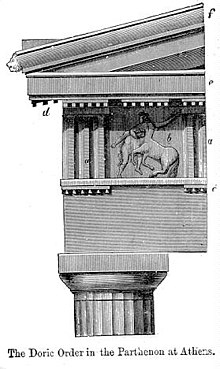

The Doric capital is the simplest of the five Classical orders: it consists of the abacus above an ovolo molding, with an astragal collar set below. It was developed in the lands occupied by the Dorians, one of the two principal divisions of the Greek race. It became the preferred style of the Greek mainland and the western colonies (southern Italy and Sicily). In the Temple of Apollo, Syracuse (c. 700 BC), the echinus moulding has become a more definite form: this in the Parthenon reaches its culmination, where the convexity is at the top and bottom with a delicate uniting curve. The sloping side of the echinus becomes flatter in the later examples, and in the Colosseum at Rome forms a quarter round (see Doric order). In versions where the frieze and other elements are simpler the same form of capital is described as being in the Tuscan order. Doric reached its peak in the mid-5th century BC, and was one of the orders accepted by the Romans. Its characteristics are masculinity, strength and solidity.

The Doric capital consists of a cushion-like convex moulding known as an echinus, and a square slab termed an abacus.

Ionic

[edit]

In the Ionic capital, spirally coiled volutes are inserted between the abacus and the ovolo. This order appears to have been developed contemporaneously with the Doric, though it did not come into common usage and take its final shape until the mid-5th century BC. The style prevailed in Ionian lands, centred on the coast of Asia Minor and Aegean islands. The order's form was far less set than the Doric, with local variations persisting for many decades. In the Ionic capitals of the archaic Temple of Artemis at Ephesus (560 BC) the width of the abacus is twice that of its depth, consequently the earliest Ionic capital known was virtually a bracket capital. A century later, in the temple on the Ilissus, the abacus has become square (See the more complete discussion at Ionic order). According to the Roman architect Vitruvius, the Ionic order's main characteristics were beauty, femininity, and slenderness, derived from its basis on the proportion of a woman.

The volutes of an Ionic capital rest on an echinus, almost invariably carved with egg-and-dart. Above the scrolls was an abacus, more shallow than that in Doric examples, and again ornamented with egg-and-dart.

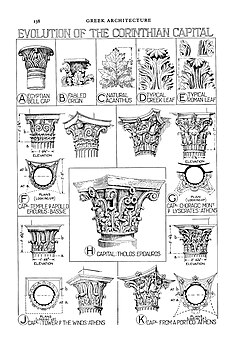

Corinthian

[edit]It has been suggested that the foliage of the Greek Corinthian capital was based on the Acanthus spinosus, that of the Roman on the Acanthus mollis. Not all architectural foliage is as realistic as Isaac Ware's (illustration, right) however. The leaves are generally carved in two "ranks" or bands, like one leafy cup set within another. The Corinthian capitals from the Tholos of Epidaurus (400 BC) illustrate the transition between the earlier Greek capital, as at Bassae, and the Roman version that Renaissance and modern architects inherited and refined (See the more complete discussion at Corinthian order).

In Roman architectural practice, capitals are briefly treated in their proper context among the detailing proper to each of the "Orders", in the only complete architectural textbook to have survived from classical times, the De architectura, by Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, better known as Vitruvius, dedicated to the emperor Augustus. The various orders are discussed in Vitruvius' books iii and iv. Vitruvius describes Roman practice in a practical fashion. He gives some tales about the invention of each of the orders, but he does not give a hard and fast set of canonical rules for the execution of capitals.

Two further, specifically Roman orders of architecture have their characteristic capitals, the sturdy and primitive Tuscan capitals, typically used in military buildings, similar to Greek Doric, but with fewer small moldings in its profile, and the invented Composite capitals not even mentioned by Vitruvius, which combined Ionic volutes and Corinthian acanthus capitals, in an order that was otherwise quite similar in proportions to the Corinthian, itself an order that Romans employed much more often than Greeks.

The increasing adoption of Composite capitals signalled a trend towards freer, more inventive (and often more coarsely carved) capitals in Late Antiquity.

Anta

[edit]The anta capital is not a capital which is set on top of column, but rather on top of an anta, a structural post integrated to the frontal end of a wall, such as the front of the side wall of a temple.

The top of an anta is often highly decorated, usually with bands of floral motifs. The designs often respond to an order of columns, but usually with a different set of design principles.[4] In order not to protrude excessively from the wall surface, these structures tend to have a rather flat surface, forming brick-shaped capitals, called "anta capitals". Anta capitals are known from the time of the Doric order.[5]

An anta capital can sometimes be qualified as a "sofa" capital or a "sofa anta capital" when the sides of the capital broaden upward, in a shape reminiscent of a couch or sofa.[6][7][8]

Anta capitals are sometimes hard to distinguish from pilaster capitals, which are rather decorative, and do not have the same structural role as anta capitals.

Roman

[edit]Tuscan

[edit]The origins of the Tuscan order lie with the Etruscans and are found on their tombs. Although the Romans perceived it as especially Italianate, the Tuscan capital found on Roman monuments is in fact closer to the Greek Doric order than to Etruscan examples, its capital being nearby identical with the Doric.

Composite

[edit]The Romans invented the Composite order by uniting the Corinthian order with the Ionic capital, possibly as early as Augustus's reign. In many versions the Composite order volutes are larger, however, and there is generally some ornament placed centrally between the volutes. Despite this origin, very many Composite capitals in fact treat the two volutes as different elements, each springing from one side of their leafy base. In this, and in having a separate ornament between them, they resemble the Archaic Greek Aeolic order, though this seems not to have been the route of their development in early Imperial Rome. Equally, where the Greek Ionic volute is usually shown from the side as a single unit of unchanged width between the front and back of the column, the Composite volutes are normally treated as four different thinner units, one at each corner of the capital, projecting at some 45° to the façade.

Indian

[edit]The Lion Capital of Ashoka

[edit]

The Lion Capital of Ashoka is an iconic capital which consists of four Asiatic lions standing back to back, on an elaborate base that includes other animals. A graphic representation of it was adopted as the official Emblem of India in 1950.[9] This powerfully carved lion capital from Sarnath stood a top a pillar bearing the edicts of the emperor Ashoka. Like most of Ashoka's capitals, it is brilliantly polished. Located at the site of Buddha's first sermon and the formation of the Buddhist order, it carried imperial and Buddhist symbols, reflecting the universal authority of both the emperor's and the Buddha's words. The capital today serves as the emblem of the Republic of India. Minus the inverted bell-shaped lotus flower, this has been adopted as the National Emblem of India, seen from another angle, showing the horse on the left and the bull on the right of the Ashoka Chakra in the circular base on which the four Indian lions are standing back to back. On the side shown here there are the bull and elephant; a lion occupies the other place. The wheel "Ashoka Chakra" from its base has been placed onto the centre of the National Flag of India

Indo-Ionic capitals

[edit]The Pataliputra capital is a monumental rectangular capital with volutes designs, that was discovered in the palace ruins of the ancient Mauryan Empire capital city of Pataliputra (modern Patna, northeastern India). It is dated to the 3rd century BC. The top is made of a band of rosettes, eleven in total for the fronts and four for the sides. Below that is a band of bead and reel pattern, then under it a band of waves, generally right-to-left, except for the back where they are left-to-right. Further below is a band of egg-and-dart pattern, with eleven "tongues" or "eggs" on the front, and only seven on the back. Below appears the main motif, a flame palmette, growing among pebbles.

The Sarnath capital is a pillar capital, sometimes also described as a "stone bracket", discovered in the archaeological excavations at the ancient Buddhist site of Sarnath. The pillar displays Ionic volutes and palmettes.[10][11] It has been variously dated from the 3rd century BCE during the Mauryan Empire period,[12] to the 1st century BCE, during the Sunga Empire period.[10]

Indo-Corinthian capitals

[edit]

Some capitals with strong Greek and Persian influence have been found in northeastern India in the Maurya Empire palace of Pataliputra, dating to the 4th–3rd century BC. Examples such as the Pataliputra capital belong to the Ionic order rather than the later Corinthian order. They are witness to relations between India and the West from that early time.

Indo-Corinthian capitals correspond to the much more abundant Corinthian-style capitals crowning columns or pilasters, which can be found in the northwestern Indian subcontinent, particularly in Gandhara, and usually combine Hellenistic and Indian elements. These capitals are typically dated to the first century BC, and constitute important elements of Greco-Buddhist art.

The Classical design was often adapted, usually taking a more elongated form, and sometimes being combined with scrolls, generally within the context of Buddhist stupas and temples. Indo-Corinthian capitals also incorporated figures of the Buddha or Bodhisattvas, usually as central figures surrounded by, and often under the shade of, the luxurious foliage of Corinthian designs.

Late Antiquity

[edit]Byzantine

[edit]

Byzantine capitals vary widely, mostly developing from the classical Corinthian, but tending to have an even surface level, with the ornamentation undercut with drills. The block of stone was left rough as it came from the quarry, and the sculptor evolved new designs to his own fancy, so that one rarely meets with many repetitions of the same design. One of the most remarkable designs features leaves carved as if blown by the wind; the finest example being at the 8th-century Hagia Sophia (Thessaloniki). Those in the Cathedral of Saint Mark, Venice (1071) specially attracted John Ruskin's fancy. Others appear in Sant'Apollinare in Classe, Ravenna (549).

The capital in San Vitale, Ravenna (547) shows above it the dosseret required to carry the arch, the springing of which was much wider than the abacus of the capital. On eastern capitals the eagle, the lion and the lamb are occasionally carved, but treated conventionally.

There are two types of capitals used at Hagia Sophia: Composite and Ionic. The composite capital that emerged during the Late Byzantine Empire, mainly in Rome, combines the Corinthian with the Ionic. Composite capitals line the principal space of the nave. Ionic capitals are used behind them in the side spaces, in a mirror position relative to the Corinthian or composite orders (as was their fate well into the 19th century, when buildings were designed for the first time with a monumental Ionic order). At Hagia Sophia, though, these are not the standard imperial statements. The capitals are filled with foliage in all sorts of variations. In some, the small, lush leaves appear to be caught up in the spinning of the scrolls – clearly, a different, nonclassical sensibility has taken over the design.

The capitals at Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna (Italy) show wavy and delicate floral patterns similar to decorations found on belt buckles and dagger blades. Their inverted pyramidal form has the look of a basket.

Capitals in early Islamic architecture are derived from Graeco-Roman and Byzantine forms, reflecting the training of most of the masons producing them.

-

Illustration of the Corinthian capital of the mid-5th-century Column of Marcian, with a pulvino above it.

-

Corinthian capital from the late 5th-century "Basilica A" at Philippi

-

Capital from the late 5th-century "Basilica A" at Philippi

-

Corinthian capital from the early 6th-century Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo (Ravenna, Italy)

-

Capital in the mid-6th century Basilica of San Vitale (Ravenna, Italy)

-

Basket capital in the atrium of the 6th-century Euphrasian Basilica, Poreč

-

Capital with protomes of pegasi, probably 6th-century, possibly from the Hippodrome of Constantinople

-

One of the "Pilastri Acritani", Venice, from the 6th-century Church of St Polyeuctus in Constantinople

-

Byzantine Ionic capital from Dyrrachium (Durrës) in the National Museum of Medieval Art (Korçë, Albania)

-

10th-century Islamic Composite capital with Arabic-inscribed abacus, probably from Medina Azahara, in the Umayyad Caliphate of Córdoba (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

-

10th-century capitals from the Umayyad Caliphate of Córdoba (Louvre)

Middle Ages

[edit]

In both periods small columns are often used close together in groups, often around a pier that is in effect a single larger column, or running along a wall surface. The structural importance of the individual column is thereby greatly reduced. In both periods, though there are common types, the sense of a strict order with rules was not maintained, and when the budget allowed, carvers were able to indulge their inventiveness. Capitals were sometimes used to hold depictions of figures and narrative scenes, especially in the Romanesque.

In Romanesque architecture and Gothic architecture capitals throughout western Europe present as much variety as in the East, and for the same reason, that the sculptor evolved his design in accordance with the block he was carving, but in the west variety goes further, because of the clustering of columns and piers.

The earliest type of capital in Lombardy and Germany is known as the cushion-cap, in which the lower portion of the cube block has been cut away to meet the circular shaft. These types were generally painted at first with geometrical designs, afterwards carved.

The finest carving comes from France, especially from the area around Paris. The most varied were carved in 1130–1170.[13]

In Britain and France the figures introduced into the capitals are sometimes full of character, these are referred to as historiated (or figured capital). These capitals, however, are not equal to those of the Early English Gothic, in which foliage is treated as if copied from metalwork, and is of infinite variety, being found in small village churches as well as in cathedrals.

-

Simple, Romanesque cushion capital in the crypt of Lund Cathedral (Sweden)

-

Romanesque capital at the abbey of Saint-Michel-de-Cuxa (France)

-

Gothic capitals at a portal of Marienkirche Gelnhausen (Gelnhausen, Germany)

Armenian

[edit]

Armenian capitals are often versions of Byzantine forms. In the 4th-7th centuries the capitals of Armenian architectural facades and masonry facades are tall rectangular stones with a total volume, which are converted into a slab by means of a bell. In the structures of the early period (Ereruyk, Tekor, Tsopk, etc.) they were sculpted with plant and animal images, palm trees. In the 10th century and in the following centuries, capitals are mainly formed by a combination of a cylinder and a slab. The structures of Armenian palaces, churches, courtyards (Dvin, Aruch, Zvartnots, Ishkhan, Banak, Haghpat, Sanahin, Ani structures) are diverse and unique.

Renaissance and post-Renaissance

[edit]

In the Renaissance period the feature became of the greatest importance and its variety almost as great as in the Romanesque and Gothic styles. The flat pilaster, which was employed extensively in this period, called for a planar rendition of the capital, executed in high relief. This affected the designs of capitals. A traditional 15th-century variant of the Composite capital turns the volutes inwards above stiffened leaf carving. In new Renaissance combinations in capital designs most of the ornament can be traced to Classical Roman sources.

The 'Renaissance' was as much a reinterpretation as a revival of Classical norms. For example, the volutes of ancient Greek and Roman Ionic capitals had lain in the same plane as the architrave above them. This had created an awkward transition at the corner – where, for example, the designer of the temple of Athena Nike on the Acropolis in Athens had brought the outside volute of the end capitals forward at a 45-degree angle. This problem was more satisfactorily solved by the 16th-century architect Sebastiano Serlio, who angled outwards all volutes of his Ionic capitals. Since then use of antique Ionic capitals, instead of Serlio's version, has lent an archaic air to the entire context, as in Greek Revival.

There are numerous newly invented orders, sometimes called nonce orders, where a different ornamentation of the capital is typically a key feature. Within the bounds of decorum, a certain amount of inventive play has always been acceptable within the classical tradition. These became increasingly common after the Renaissance. When Benjamin Latrobe redesigned the Senate Vestibule in the United States Capitol in 1807, he introduced six columns that he "Americanized" with ears of corn (maize) substituting for the European acanthus leaves. As Latrobe reported to Thomas Jefferson in August 1809,

- These capitals during the summer session obtained me more applause from members of Congress than all the works of magnitude or difficulty that surround them. They christened them the 'corncob capitals'.

Another example is the Delhi Order invented by the British architect Edwin Lutyens for New Delhi's central palace, Viceroy's House, now the Presidential residence Rashtrapati Bhavan, using elements of Indian architecture.[14] Here the capital had a band of vertical ridges, with bells hanging at each corner as a replacement for volutes.[15] The Delhi Order reappears in some later Lutyens buildings including Campion Hall, Oxford.[16]

-

Illustrations of Baroque capitals from France, in the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum (New York City)

-

Illustrations of Baroque pilaster capitals from France, in the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

-

The capitals of a Rococo pilaster, on the Mausoleum Althan (Austria)

-

Composite capital of Réverbère de la place de la Concorde, in Paris

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Arnold, 2005, pp.204ff

- ^ Mumcuoglu, Madeleine; Garfinkel, Yosef (2021). "Royal Architecture in the Iron Age Levant". Jerusalem Journal of Archaeology. 1 (1). Hebrew University of Jerusalem: 450–481 [464–472]. doi:10.52486/01.00001.15 (inactive 1 November 2024). S2CID 236257877. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ "Can royal architecture prove biblical Judah was a kingdom?". Rossella Tercatin for The Jerusalem Post. 21 November 2021. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- ^ "The Classical Orders of Architecture" Robert Chitham, Routledge, 2007 p.212 [1]

- ^ "The Classical Orders of Architecture" Robert Chitham, Routledge, 2007 p.31 [2]

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 02 (11th ed.). 1911.

- ^ Architectural Elements, Emory University [3] Archived 2016-03-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Architectural Elements | Samothrace". Archived from the original on 2016-03-16. Retrieved 2016-11-02.

- ^ State Emblem, Know India india.gov.in

- ^ a b Mani, B. R. (2012). Sarnath : Archaeology, Art and Architecture. Archaeological Survey of India. p. 60.

- ^ Majumdar, B. (1937). Guide to Sarnath. p. 41.

- ^ Presented as a "Mauryan capital, 250 BC" with the addition of recumbant lions at the base, in the page "Types of early capitals" in Brown, Percy (1959). Indian Architecture (Buddhist And Hindu). p. x.

- ^ John James, The Creation of Gothic Architecture – an Illustrated Thesaurus: The Ark of God, vols. 5, London and Hartley Vale, 2002/2008.

- ^ Gradidge, Roderick (1981). Edwin Lutyens: Architect Laureate. London: George Allen and Unwin. p. 69. ISBN 0-04-720023-5.

- ^ Gradidge, Roderick (1981). Edwin Lutyens: Architect Laureate. London: George Allen and Unwin. p. 151. ISBN 0-04-720023-5.

- ^ Gradidge, Roderick (1981). Edwin Lutyens: Architect Laureate. London: George Allen and Unwin. p. 161. ISBN 0-04-720023-5.

- Lewis, Philippa & Gillian Darley (1986) Dictionary of Ornament, NY: Pantheon

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Capital (architecture)". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.