Waterworld

| Waterworld | |

|---|---|

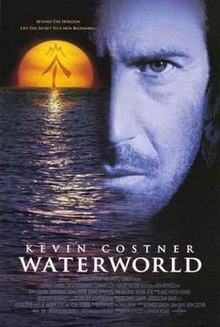

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Kevin Reynolds |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by | |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Dean Semler |

| Edited by | Peter Boyle |

| Music by | James Newton Howard |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 135 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $172–175 million[2][3] |

| Box office | $264.2 million[3] |

Waterworld is a 1995 American post-apocalyptic action film directed by Kevin Reynolds and co-written by Peter Rader and David Twohy. It was based on Rader's original 1986 screenplay and stars Kevin Costner, who also produced it with Charles Gordon and John Davis. It was distributed by Universal Pictures.

The setting of the film is in the distant future. The polar ice caps have completely melted, and the sea level has risen over 7,600 m (25,000 ft), covering nearly all of the land. The plot of the film centers on a nameless antihero, "The Mariner", a drifter who sails the Earth in his trimaran.

The most expensive film ever made at the time, Waterworld was released to mixed reviews from critics, who praised the futuristic setting and premise, but criticized the execution, including the characterization and acting performances. The film also was unable to recoup its massive budget at the box office despite being the ninth highest-grossing film of 1995; however, the film did later become profitable owing to video and other post-cinema sales. The film was nominated for an Academy Award in the category Best Sound at the 68th Academy Awards.

The film's release was accompanied by a novelization, video games, and four themed attractions at Universal Studios Hollywood, Universal Studios Singapore, Universal Studios Japan, and Universal Studios Beijing called WaterWorld, all of which are still running as of 2024[update].

Plot

[edit]In 2500,[4] sea level rises had swallowed every continent on Earth underwater. The remains of human civilization live on makeshift floating communities built out of scavenged materials known as atolls, having long forgotten about living on land. Rumors of a "Dryland" still float around, but most consider it a myth.

The Mariner, a lone drifter, arrives at an atoll on his trimaran to trade dirt - a rare commodity - for supplies. When the locals discover he is a mutant, with gills and webbed feet, several accost him and he kills one in self-defense. As a result, the Mariner is sentenced to be drowned in a tank of compost.

As the sentence proceeds, the atoll is raided by the Smokers, a formidable pirate gang that has been systematically raiding and destroying atolls. Helen, a strong-willed atoll resident, tries to escape with her young ward Enola on a gas balloon dirigible created by inventor Gregor. However, Gregor accidentally departs with only himself onboard, stranding the two. Helen frees the Mariner on the condition he takes them with him. The Mariner skillfully fights his way out, damaging the Smokers' forces and causing an explosion that blinds its leader, Deacon, in one eye. The Mariner, Helena and Enola board the trimaran and escape.

Despite his initial reluctance and gruff attitude, the Mariner slowly warms up to his companions and has a bonding moment with Enola teaching her to swim. As they flee the Smokers, the trio encounters an unstable drifter whom the Mariner kills after a trade-gone-wrong, a mutated shark the Mariner kills for food.

After evading a trap set by the Smokers, the Mariner confronts Helen about the Smokers' unusual persistence. She admits they are after Enola, for the supposed directions to Dryland tattooed on her back. The Mariner gets Helen in a diving bell and shows her the underwater remains of Denver, Colorado and the soil on the ocean's floor, crushing her belief in Dryland. When they surface, they find that the Smokers have caught up. The Smokers capture Enola and try to kill Helen and the Mariner before the two dive underwater. Before the Smokers leave, they destroy the trimaran by setting it on fire.

Sorting through the wreckage of his boat, the Mariner sees National Geographic magazines and compares their images to Enola's doodles, realizing she was drawing Dryland objects. Gregor, having spotted the smoke from his dirigible, finds Helen and the Mariner and takes them to a new makeshift atoll. The Mariner takes a captured Smoker's jet ski to chase down the Smokers' base of operations, the remains of the Exxon Valdez, where they manage to manufacture gasoline, ammunition and cigarettes.

Meanwhile, the Deacon's advisors struggle to decipher the tattoo. Regardless, the Deacon makes a grand speech, using Enola and hopes of Dryland to keep his followers' minds off their dwindling resources, then sends them back to their stations to mindlessly row the "'Dez".

The Mariner infiltrates the "'Dez," confronts the Deacon, and threatens to ignite the oil reserves in the hold. The Deacon calls the Mariner's bluff, but to his shock, the Mariner drops a flare into the oil reservoir. The ship is engulfed in flames, and begins to sink. The Mariner rescues Enola and escapes via a rope from Gregor's balloon. The Deacon fires at the balloon, shaking Enola into the ocean. As the Deacon and two of his men converge on her, the Mariner makes an impromptu bungee jump from the balloon to grab Enola. The Deacon and his men's jet-skis collide, causing an explosion which kills all three.

Gregor eventually manages to decipher Enola's tattoo. Following the map, the balloon party discover Dryland, covered with vegetation and wildlife. They also find a hut with the remains of Enola's parents. The Mariner, feeling he does not belong, takes an old wooden catamaran from the island and departs, as Helen and Enola bid him farewell.

Ulysses Cut

[edit]The extended cut, dubbed the "Ulysses Cut", has a runtime of 171 minutes and features scenes that flesh out the characters and settings. It identifies the Dryland as Mt. Everest, and ends with Helen gifting the Mariner with the name Ulysses.

Cast

[edit]- Kevin Costner as The Mariner

- Dennis Hopper as The Deacon

- Jeanne Tripplehorn as Helen

- Tina Majorino as Enola

- Michael Jeter as Old Gregor

- Gerard Murphy as The Nord

- R. D. Call as Atoll Enforcer

- Kim Coates as Drifter #2

- John Fleck as Smoker Doctor

- Robert Joy as Smoker Ledger Guy

- Jack Black as Smoker Plane Pilot

- John Toles-Bey as Smoker Plane Gunner (Ed)

- Robert LaSardo as Smitty

- Zakes Mokae as Priam

- Zitto Kazann, Sab Shimono, and Leonardo Cimino as Atoll Elders

- Rick Aviles as Atoll Gatesman #1

- Jack Kehler as Atoll Banker

- Chris Douridas as Atoller #7

- Robert A. Silverman as Hydroholic

- Neil Giuntoli as Hellfire Gunner (Chuck)

- William Preston as Smoker Depth Gauge Guy

- Sean Whalen as Bone

- Lee Arenberg as Djeng

Production

[edit]Writer Peter Rader came up with the idea for Waterworld during a conversation with Brad Krevoy where they discussed creating a Mad Max rip-off.[5][6] Rader wrote the initial script in 1986 but kept it shelved until 1989. Rader cited Mad Max as a direct inspiration for the film, while also citing various Old Testament stories and the story of Helen of Troy (with the main female character being named Helen in a direct reference). It is also widely believed that inspiration was taken from Freakwave by Peter Milligan and Brendan McCarthy, a "Mad Max goes surfing" comic strip first published by Pacific Comics in Vanguard Illustrated #1-3 (November 1983-March 1984), and continued by Eclipse Comics in Strange Days #1-3 (November 1984-April 1985). McCarthy himself had unsuccessfully tried to sell Freakwave as a movie in the early 1980s; he would go on to co-write Mad Max: Fury Road (2015).[7][6]

After several rewrites, Kevin Costner and Kevin Reynolds joined the Waterworld production team in 1992.[8] The film marked the fourth collaboration between Costner and Reynolds, who had previously worked together on Fandango (1985), Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991), and Rapa-Nui (1994), the latter of which Costner co-produced but did not star in.[9] Waterworld was co-written by David Twohy, who cited Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior as a major inspiration. Both films employed Dean Semler as director of photography.

During production, the film was plagued by a series of cost overruns and production setbacks.[9] Universal initially authorized a budget of $100 million,[note 1] which by mid-1994 had swollen to $135 million, with final costs reaching an estimated $175 million, a record sum for a film production at the time.[9] Filming took place in a large artificial seawater enclosure similar to that used in the film Titanic two years later; it was located in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of Hawaii. The final scene was filmed in Waipio Valley on the Big Island, also referred to as The Valley of Kings. Additional filming took place in Los Angeles, Huntington Beach, and Santa Catalina Island, and the Channel Islands of California. Before filming began, Steven Spielberg had warned Costner and Reynolds not to film on open water owing to his own production difficulties with Jaws.[11] The production was hampered by difficulties in obtaining otherwise simple shots due to poor weather, safety concerns, and the camera crew being pushed out of position by waves.[12] One of the floating sets sank in heavy seas, and had to be repaired. [note 2] Eventually the production had to be extended by nearly three months, from 96 days to over 150. The state of Hawaii had more than $35 million added to its economy as a result of the colossal film production.[14]

The production featured different types of personal watercraft, especially Kawasaki jet skis. Kevin Costner was on the set for 157 days, working six days a week.[15] At one point, he nearly died when he got caught in a squall while tied to the mast of his trimaran.[16] Professional surfer Laird Hamilton was Kevin Costner's stunt double for many water scenes. Hamilton commuted to the set via jet ski.

Mark Isham's score, which was not recorded for approximately 25 percent of the film and had only demos completed, was reportedly rejected by Costner because it was "too ethnic and bleak", contrasting with the film's futuristic and adventurous tone; Isham offered to try again but was not given the chance.[17] James Newton Howard was brought in to write the new score. Joss Whedon flew out to the set to do last minute script rewrites and later described it as "seven weeks of hell"; the work boiled down to editing in Costner's ideas without alteration.[18][19]

Inspired by racing trimarans built by Jeanneau Advanced Technologies' multi-hull division, Lagoon, a custom 60 foot (18 m) yacht was designed by Marc Van Peteghem and Vincent Lauriot-Prevost and built in France by Lagoon. Two versions were built, a relatively standard racing trimaran for distance shots, and an effects-laden transforming trimaran for closeup shots. The first trimaran was launched on 2 April 1994, and surpassed 30 knots (56 km/h; 35 mph) in September of that year.[20] The transforming version was first seen in the film as a sort of raft with a three-bladed egg-beater windmill. When needed, levers could be triggered that would flatten the windmill blades while raising a hidden mast to full racing height. A boom emerged, previously hidden in the hull, and the two sails were automatically unfurled. Once the transformation was complete, this version could actually sail, although not as well as the dedicated racer.[20] The transforming version is in private hands in San Diego, California.[20] For many years, the racing version was kept on a lake at Universal Studios Florida,[20] before being restored for use as a racing trimaran named Loe Real, which was (as of 2012) being offered for sale in San Diego.[21]

Kevin Reynolds quit the film before its release, owing to heated battles with Costner over his creative decisions.[5][22] Reynolds still received full credit as director.[23] Despite their reported clashes, the director and star reunited almost two decades later for the History Channel miniseries Hatfields & McCoys.

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]Because of the runaway costs of the production and its expensive price tag, some critics dubbed it "Fishtar"[24] and "Kevin's Gate",[25] alluding to the flops Ishtar and Heaven's Gate, although the film debuted at the box office at No. 1.[26][27] For its first weekend, Waterworld collected a total of $21.6 million.[28] With a budget of $172 million (and a total outlay of $235 million once marketing and distribution costs are factored in),[2] the film grossed $88 million at the North American box office. The film did better overseas, with $176 million at the foreign box office, for a worldwide total of $264 million.[3] However, even though this figure surpasses the total costs spent by the studio, it does not take into account the percentage of box office gross that theaters retain, which is generally up to half;[2] but after factoring in home video sales and TV broadcast rights among other revenue streams, Waterworld eventually became profitable.[29][30]

Critical response

[edit]Contemporary reviews for the film were mixed. Roger Ebert gave Waterworld 2.5 stars out of 4 and said: "The cost controversy aside, Waterworld is a decent futuristic action picture with some great sets, some intriguing ideas, and a few images that will stay with me. It could have been more, it could have been better, and it could have made me care about the characters. It's one of those marginal pictures you're not unhappy to have seen, but can't quite recommend."[31] Owen Gleiberman gave it a B in Entertainment Weekly. He commented that while its massive budget had paid off by genuinely creating the sensation of a world built on water, the film generally came off as a second-rate rip-off of The Road Warrior, with weaker, slower-paced action sequences and less startling villains. He praised Costner's performance, but found the film's environmental message pretentious.[32] James Berardinelli of Reelviews Movie Reviews was one of the film's few supporters, calling it "one of Hollywood's most lavish features to date". He wrote: "Although the storyline isn't all that invigorating, the action is, and that's what saves Waterworld. In the tradition of the old Westerns and Mel Gibson's Mad Max flicks, this film provides good escapist fun. Everyone behind the scenes did their part with aplomb, and the result is a feast for the eyes and ears."[33] Mick LaSalle, reviewing the film the week of its release on home video, argued that it did not deserve some of its more negative reviews, since "despite its confused impulses and occasional slow spots, Waterworld... has an elusive, appealing spirit that holds up for more than two hours. It's a genuine vault at greatness that misses the mark -- but survives." He commented that while the film succeeds at its high ambitions for isolated moments, the clash between its earnest ambition and intrusive flashiness makes it generally fall short of its reach.[34]

On Rotten Tomatoes the film holds an approval rating of 47% based on 66 reviews, with an average rating of 5.5/10. The site's critics consensus reads: "Though it suffered from toxic buzz at the time of its release, Waterworld is ultimately an ambitious misfire: an extravagant sci-fi flick with some decent moments and a lot of silly ones."[35] Metacritic assigned the film a weighted average score of 56 out of 100, based on 17 critics, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[36] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "B" on an A+ to F scale.[37]

In a 2020 retrospective, Ben Child of The Guardian described it as "a perfectly watchable sci-fi cult classic" that deserves reappraisal. He acknowledged that much of the plot was illogical and absurd and some of the action set-pieces "preposterously ambitious", but argued that both of them offer excitement and B-movie charm.[38]

Cast and director's reception

[edit]Kevin Costner said he's very fond of the film: "It stands up as a really exotic, cool movie. I mean, it was flawed — for sure. But, overall, it's a very inventive, cool movie. It's pretty robust."[39] Dennis Hopper also enjoyed it, saying "I thought Waterworld got a bad name for itself in the United States, but it did really well in Europe and Asia. I think the studio sort of shot themselves in the foot by announcing it was so over budget, blah blah blah, it's going to be a failure... All this came out before we released it in the States. But I enjoyed it."[40] In retrospect, Director Kevin Reynolds said: "My own personal take on the picture is that I don't think it's any better, any worse than most summer blockbusters, it's somewhere in the middle. I think yeah, it's certainly got its faults, but I think, you know, on another level I think it works quite well compared to some of the other big films. But by the end, people…they wanted it to be a disaster."[41]

Accolades

[edit]| Award | Subject | Nominee | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards[42] | Best Sound | Steve Maslow, Gregg Landaker and Keith A. Wester | Nominated |

| British Academy Film Awards[43] | Best Special Visual Effects | Michael J. McAlister, Brad Kuehn, Robert Spurlock and Martin Bresin | Nominated |

| Golden Raspberry Awards[44] | Worst Picture | Charles Gordon, John Davis, and Kevin Costner | Nominated |

| Worst Director | Kevin Reynolds | Nominated | |

| Worst Actor | Kevin Costner | Nominated | |

| Worst Supporting Actor | Dennis Hopper | Won | |

| Saturn Awards[45][46] | Best Science Fiction Film | Nominated | |

| Best Costume | John Bloomfield | Nominated | |

| Best DVD or Blu-ray Special Edition Release | Won |

Other media

[edit]Home media

[edit]Waterworld was released on VHS and LaserDisc on January 23, 1996.[47] On September 9, 1997, it debuted on a THX certified widescreen VHS release.[48] The film was then released on DVD on November 1, 1998, on Blu-ray on October 20, 2009,[49] and on 4K Blu-ray on July 9, 2019.[50]

Novelization

[edit]A novelization was written by Max Allan Collins and published by Arrow Books. It goes into greater detail regarding the world of the film.

Comic books

[edit]A sequel comic book four-issue mini-series entitled Waterworld: Children of Leviathan, drawn by Kevin Kobasic,[51] was released by Acclaim Comics in 1997. Kevin Costner did not permit his likeness to be used for the comics, so the Mariner looks different. The story reveals some of the Mariner's back-story as he gathers clues about where he came from and why he is different. The comic expands on the possible cause of the melting of the polar ice caps and worldwide flood, and introduces a new villain, "Leviathan", who supplied the Deacon's Smoker organization. The comic hints at the possibility that the Mariner's mutation may not be caused by evolution but by genetic engineering and that his origins may be linked to those of the "Sea Eater", the sea monster seen during the fishing scene in the film.

Video games

[edit]Video games based on the film were released for the Super NES, Game Boy, Virtual Boy, and PC. There was to be a release for the Genesis, but it was canceled and was only available on the Sega Channel. A Sega Saturn version of the game was also planned, and development was completed, but like its Genesis counterpart it was cancelled prior to release. The Super NES and Game Boy releases were only available in the United Kingdom and Australia. While the Super NES and Virtual Boy versions were released by Ocean Software, the PC version was released by Interplay. The Virtual Boy version of the game was the only movie licensed game for the system.

Pinball

[edit]The film was released as a pinball machine[52] in 1995 by Gottlieb Amusements (later Premier, both now defunct).

Theme park attraction

[edit]There are attractions at Universal Studios Hollywood, Universal Studios Japan, and Universal Studios Singapore based on the film. The show's plot takes place after the film, as Helen returns to the Atoll with proof of Dryland, only to find herself followed by the Deacon, who survived the events of the film. The Mariner arrives after him, defeats the Deacon and takes Helen back to Dryland.

TV series

[edit]In July 2021, it was announced Universal Cable Productions was in early development on a follow-up TV series to be directed by Dan Trachtenberg.[53]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ In an interview with Starlog, Costner stated that the original budget was approximately $135 million, but Universal, which was wary of greenlighting a film with a budget over $100 million, greenlit the film with a $65 million budget.[10]

- ^ Contrary to rumors, this was not the multimillion dollar atoll set, but rather the smaller slave colony one, and the event occurred after the bulk of shooting had already finished.[13]

References

[edit]- ^ "WATERWORLD (12)". British Board of Film Classification. July 26, 1995. Archived from the original on October 16, 2012. Retrieved May 24, 2012.

- ^ a b c Weinraub, Bernard (July 31, 2010). "'Waterworld' Disappointment As Box Office Receipts Lag". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 24, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Waterworld (1995)". Box Office Mojo. September 26, 1995. Archived from the original on July 7, 2019. Retrieved January 3, 2010.

- ^ Although no exact date was given in the film itself, it has been suggested that it takes place in 2500. [The Making of Waterworld by Janine Pourroy (August 1995). Production designer Dennis Gassner states: "The date was 2500."]

- ^ a b Parish, James (2007). Fiasco: A History of Hollywood's Iconic Flops. United States: Trade Paper Press. p. 252. ISBN 978-0470098295.

- ^ a b Lambie, Ryan (July 24, 2017). "How Waterworld Became a $175 Million Epic". Den of Geek.

- ^ "Cult Classic Comics: FREAKWAVE Pt. 1". Off the Beaten Panel. August 2012. Archived from the original on April 18, 2021. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ Johnson, Kim Howard (September 1995). "Rime of the Future Mariner". Starlog. No. 218. pp. 40–44 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b c Eller, Claudia; Welkos, Robert W. (September 16, 1994). "Plenty of Riptides on 'Waterworld' Set: With key crew people quitting and reported turmoil, logistical and organizational problems, the big-budget film, scheduled for release in summer of '95, could end up costing more than any movie ever made". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 21, 2014. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- ^ Shapiro, Marc (October 1995). "Storm Gathering". Starlog. No. 219. pp. 50–53 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "'Waterworld' at 25: How Kevin Costner's choice to ignore Steven Spielberg resulted in one of the most expensive movies ever". Yahoo Entertainment. 2020. Archived from the original on July 28, 2020. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- ^ "'Fishtar'? Why 'Waterworld,' With Costner in Fins, Is Costliest Film Ever". Wall Street Journal. January 31, 1995. Retrieved May 11, 2023.

- ^ "Waterworld -- The Big Guys Go On Record About All Those Rumors". The Seattle Times. July 28, 1995. Retrieved May 12, 2023.

Report: The movie's most expensive set, the $4 million, 126-ton atoll, sank during production - Actually it was the smaller "slave colony" set and, Gordon says, the bulk of the shooting already had been completed, and most of the crew had returned to L.A.

- ^ "The Most Expensive Movies Ever Made". Forbes. Archived from the original on August 27, 2016. Retrieved January 3, 2010.

- ^ "Stashed Chats: Kevin Costner talks "Draft Day"". thestashed.com. April 10, 2014. Archived from the original on April 12, 2014. Retrieved August 5, 2014.

- ^ "Kevin Costner's Hawaii Uh-Oh". people.com. Meredith Corporation. May 29, 1995. Archived from the original on May 21, 2016. Retrieved August 5, 2014.

- ^ "Waterworld (James Newton Howard)". Filmtracks. August 1, 1995. Archived from the original on May 15, 2009. Retrieved January 3, 2010.

- ^ Sinott, John (December 10, 2006). "Waterworld and troubles for Blu-ray?". Mania.com. Archived from the original on May 4, 2010. Retrieved January 3, 2010.

- ^ Robinson, Tasha (September 5, 2001). "Joss Whedon". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on February 24, 2009. Retrieved August 19, 2012.

- ^ a b c d "The Mariner's Trimaran". October 27, 2009. Archived from the original on October 27, 2009.

- ^ ""Loe Real" - 60' Jeanneau Custom Trimaran". Morrelli & Melvin. 2012. Archived from the original on April 19, 2014. Retrieved April 17, 2014.

- ^ Goldstein, Patrick (September 15, 1999). "Costner's Feeling a Little Less 'Love". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ Reynolds, Kevin (1995). Waterworld (Film). Universal City Studios. Event occurs at 02:15:11.

Directed by Kevin Reynolds

- ^ "Waterworld (PG-13)". The Washington Post. July 28, 1995. Archived from the original on December 2, 2017. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ^ "Married with Movies: Waterworld - Two-Disc Extended Edition". Archived from the original on March 10, 2011. Retrieved July 16, 2013.

- ^ Natale, Richard (July 31, 1995). "Waterworld Sails to No. 1 : Movies: The $175-million production takes in $21.6 million in its first weekend. But unless it enlarges its appeal, it will probably gross about half its cost". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 30, 2010.

- ^ Eyerly, Alan (July 31, 1995). "Strong Opening Weekend for 'Waterworld': Fans: Why do people endure epic waits in line to see big movies? It's, like, a party". The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved December 30, 2010.

- ^ "Costner film debuts at No. 1". The Atlanta Constitution. July 31, 1995. p. 16. Archived from the original on February 27, 2023. Retrieved February 27, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (August 7, 2013). "Isn't It Time To Take 'Waterworld' Off The All-Time Flop List?". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on January 8, 2015.

- ^ Stewart, Andrew (August 11, 2012). "B.O. reality gets lost in perception". Variety. Archived from the original on July 12, 2018. Retrieved July 18, 2016.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (July 28, 1995). "Waterworld". The Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on February 13, 2013. Retrieved March 28, 2011.

- ^ Gleiberman, Owen (August 4, 1995). "Waterworld". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on July 5, 2020. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ Berardinelli, James (1995). "Waterworld". Reelviews. Archived from the original on June 5, 2020. Retrieved December 2, 2010.

- ^ LaSalle, Mick (January 26, 1996). "Film Review -- 'Waterworld' Isn't All Wet / Pricey Costner Epic has Appealing Spirit". SFGate. Archived from the original on August 11, 2020. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ "Waterworld (1995)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on March 11, 2021. Retrieved March 28, 2024.

- ^ "Waterworld Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on December 14, 2016. Retrieved June 10, 2013.

- ^ "'Waterworld' hits theaters". Entertainment Weekly. August 11, 1995. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

- ^ Child, Ben (July 30, 2020). "Waterworld: is Kevin Costner's damp squib a cult classic in the making?". the Guardian. Archived from the original on July 30, 2020. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- ^ "Kevin Costner Defends 'Waterworld' and 'The Postman'". June 5, 2013. Archived from the original on July 1, 2021. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- ^ "Random Roles: Dennis Hopper". The A.V. Club. December 2, 2008. Archived from the original on July 1, 2021. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- ^ "Kevin Reynolds: The den of Geek interview". July 27, 2008.

- ^ "The 68th Academy Awards (1996) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Archived from the original on September 29, 2012. Retrieved October 23, 2011.

- ^ "Film in 1996 | BAFTA". bafta.org. British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Retrieved September 24, 2021.

- ^ "Razzie Awards". Internet Movie Database. 1996. Archived from the original on February 23, 2009. Retrieved June 29, 2018.

- ^ "1995 – 22nd Saturn Awards". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 17, 2006. Retrieved September 24, 2021.

- ^ Mancuso, Vinnie (July 15, 2019). "'Avengers: Endgame', 'Game of Thrones' Lead the 2019 Saturn Awards Nominations". Collider. Archived from the original on July 16, 2019. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- ^ Cornell, Christopher (January 26, 1996). "'Waterworld' flooding shelves". Knight Ridder Newspapers. The Gazette. p. 48. Archived from the original on August 30, 2022. Retrieved August 30, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ McKay, John (September 6, 1997). "More videos present movies in original widescreen images". The Canadian Press. Brantford Expositor. p. 36. Archived from the original on March 11, 2023. Retrieved March 11, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Waterworld DVD Release Date". DVDs Release Dates. Archived from the original on June 17, 2019. Retrieved June 17, 2019.

- ^ Waterworld 4K Blu-ray, archived from the original on June 17, 2019, retrieved September 30, 2019

- ^ "Kevin Kobasic". Archived from the original on May 6, 2012. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- ^ "Internet Pinball Machine Database: Premier 'Waterworld'". Archived from the original on February 22, 2012. Retrieved June 26, 2009.

- ^ Petski, Denise (October 13, 2020). "'Waterworld' Follow-Up TV Series In The Works With Dan Trachtenberg To Direct". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved July 29, 2021.

Further reading

[edit]- Parish, James Robert (2006). Fiasco - A History of Hollywood's Iconic Flops. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-69159-4. 359 pages

External links

[edit]- 1995 films

- 1990s action adventure films

- 1990s science fiction action films

- American action adventure films

- American science fiction action films

- 1990s English-language films

- Fictional-language films

- 1990s dystopian films

- Films set in the 25th century

- American post-apocalyptic films

- American dystopian films

- Climate change films

- Flood films

- Seafaring films

- Films shot in Hawaii

- Davis Entertainment films

- Universal Pictures films

- Films directed by Kevin Reynolds

- Films produced by John Davis

- Films scored by James Newton Howard

- Films set on boats

- Films set on ships

- Films with screenplays by David Twohy

- Films with screenplays by Joss Whedon

- Czech Lion Awards winners (films)

- Fiction set on ocean planets

- Saturn Award–winning films

- Sea adventure films

- Films adapted into comics

- 1990s American films

- 1995 science fiction films

- English-language science fiction action films

- English-language action adventure films