Colorado National Monument

| Colorado National Monument | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Mesa County, Colorado, United States |

| Nearest city | Grand Junction, CO |

| Coordinates | 39°02′33″N 108°41′10″W / 39.04250°N 108.68611°W |

| Area | 20,533 acres (83.09 km2)[1] |

| Established | May 24, 1911 |

| Visitors | 375,035 (in 2017)[2] |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Colorado National Monument |

Colorado National Monument is a National Park Service unit near the city of Grand Junction, Colorado. Sheer-walled canyons cut deep into sandstone and granite–gneiss–schist rock formations. This is an area of desert land high on the Colorado Plateau, with pinyon and juniper forests on the plateau. The park hosts a wide range of wildlife, including red-tailed hawks, golden eagles, ravens, jays, desert bighorn sheep, and coyotes.[3] Activities include hiking, horseback riding, road bicycling, and scenic drives; a visitor center on the west side contains a natural history museum and gift shop. There are scenic views from trails, Rim Rock Drive, which winds along the plateau, and the campground.[4] Nearby are the Book Cliffs and the largest flat-topped mountain in the world, the Grand Mesa.

The monument's feature attraction is Monument Canyon, which runs the width of the park and includes rock formations such as Independence Monument, the Kissing Couple, and Coke Ovens. The monument includes 20,500 acres (32.0 sq mi; 83 km2), much of which has been recommended to Congress for designation as wilderness.

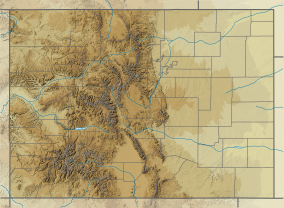

Interactive map of the Colorado National Monument

Park history

[edit]The area was first explored by John Otto, who settled in Grand Junction in the early 20th century. Prior to Otto's arrival, many area residents believed the canyons to be inaccessible to humans. Otto began building trails on the plateau and into the canyons.[5] As word spread about his work, the Chamber of Commerce of Grand Junction sent a delegation to investigate. The delegation returned praising both Otto's work and the scenic beauty of the wilderness area, and the local newspaper began lobbying to make it a National Park. A bill was introduced and carried by the local Representatives to the U.S. Congress and Senate but a Congressional slowdown in the final months threatened the process. To ensure protection of the canyons President William Howard Taft (who had visited the area) stepped in and used the highest powers available to him via the Antiquities Act and presidential proclamation to declare the canyons as a national monument.

The area was established as Colorado National Monument on May 24, 1911. Otto was hired as the first park ranger, drawing a salary of $1 per month. For the next 16 years, he continued building and maintaining trails while living in a tent in the park.

A herd of bison was introduced and maintained from 1925 to 1983.[6] After a failed effort to introduce elk, Otto obtained two cows and one bull. The herd grew to as many as 45 animals, but generally the herd was kept at about 20-25 animals.[7]

The park became more well known in the 1980s partly due to its inclusion as a stage of the major international bicycle race, the Coors Classic. The race through the park became known as "The Tour of the Moon", due to the spectacular landscapes the race passed through on Rim Rock Drive.

The issue of national park status has arisen time and again, usually during bust cycles brought on by the uranium industry and later oil and gas. As of June, 2014 Congressman Scott Tipton and Senator Mark Udall have carried the process closer to fruition than any other representatives since the initial effort in 1907. The two Representatives appointed an 18-member committee of locals to study the issue and learn the facts in 2011. After a groundswell of support from local residents and business owners, the Representatives then appointed a committee of five local residents to write draft legislation. The draft legislation was announced and released in early 2014. A public comment period on the draft legislation began soon after with an end date of June 29. Documentary producer Ken Burns (National Parks: America's Best Idea) weighed in of the effort, endorsing national park status for the Colorado National Monument. Burns compared the area to Seward, Alaska, which overcame opposition to create Kenai Fjords National Park. Burns said Seward locals came to refer to Kenai Fjords National Park as a "permanent pipeline".

Climate

[edit]Ecologically, Colorado National Monument sits on a large area of high desert in Western Colorado, though under the Köppen climate classification, it, like neighbouring Grand Junction, is temperate semi-arid. Summers are hot and dry while winters cold with some snow. Temperatures reach 100 °F (38 °C) on 6.0 days, 90 °F (32 °C) on 62.3 days, and remain at or below freezing on 12.9 days annually.[8]

| Climate data for Colorado National Monument, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1940–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 60 (16) |

66 (19) |

80 (27) |

88 (31) |

98 (37) |

104 (40) |

107 (42) |

103 (39) |

100 (38) |

88 (31) |

72 (22) |

62 (17) |

107 (42) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 50.2 (10.1) |

57.5 (14.2) |

70.5 (21.4) |

79.5 (26.4) |

88.8 (31.6) |

97.9 (36.6) |

101.4 (38.6) |

98.2 (36.8) |

92.3 (33.5) |

80.7 (27.1) |

64.5 (18.1) |

51.5 (10.8) |

102.0 (38.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 38.6 (3.7) |

44.5 (6.9) |

55.6 (13.1) |

63.1 (17.3) |

73.8 (23.2) |

86.6 (30.3) |

92.9 (33.8) |

89.6 (32.0) |

80.3 (26.8) |

65.6 (18.7) |

50.5 (10.3) |

39.0 (3.9) |

65.0 (18.3) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 29.7 (−1.3) |

34.9 (1.6) |

44.6 (7.0) |

51.0 (10.6) |

61.1 (16.2) |

72.6 (22.6) |

78.7 (25.9) |

75.7 (24.3) |

66.9 (19.4) |

53.4 (11.9) |

40.7 (4.8) |

30.4 (−0.9) |

53.3 (11.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 20.8 (−6.2) |

25.3 (−3.7) |

33.5 (0.8) |

39.0 (3.9) |

48.5 (9.2) |

58.5 (14.7) |

64.5 (18.1) |

61.7 (16.5) |

53.5 (11.9) |

41.2 (5.1) |

30.9 (−0.6) |

21.7 (−5.7) |

41.6 (5.3) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 7.9 (−13.4) |

11.8 (−11.2) |

19.6 (−6.9) |

25.6 (−3.6) |

33.3 (0.7) |

44.0 (6.7) |

54.2 (12.3) |

51.8 (11.0) |

37.9 (3.3) |

25.5 (−3.6) |

14.9 (−9.5) |

7.7 (−13.5) |

3.8 (−15.7) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −18 (−28) |

−12 (−24) |

3 (−16) |

11 (−12) |

21 (−6) |

30 (−1) |

41 (5) |

38 (3) |

27 (−3) |

2 (−17) |

−5 (−21) |

−11 (−24) |

−18 (−28) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.83 (21) |

0.64 (16) |

0.94 (24) |

1.11 (28) |

1.17 (30) |

0.65 (17) |

0.79 (20) |

1.01 (26) |

1.29 (33) |

1.26 (32) |

0.80 (20) |

0.75 (19) |

11.24 (286) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 6.2 (16) |

3.9 (9.9) |

2.1 (5.3) |

0.7 (1.8) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.6 (1.5) |

2.8 (7.1) |

5.4 (14) |

21.8 (55.85) |

| Average extreme snow depth inches (cm) | 4.4 (11) |

3.5 (8.9) |

1.2 (3.0) |

0.4 (1.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

1.8 (4.6) |

3.4 (8.6) |

5.3 (13) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 6.0 | 5.2 | 5.8 | 6.5 | 6.2 | 3.5 | 5.9 | 7.2 | 6.7 | 6.7 | 5.3 | 5.9 | 70.9 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 4.0 | 3.0 | 1.7 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 1.6 | 4.7 | 15.8 |

| Source 1: NOAA[8] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: National Weather Service[9] | |||||||||||||

Trails

[edit]

The Monument contains many hiking trails, with lengths and difficulties to suit all tastes. Summer storms can cause flash floods as well as dangerous trail conditions. Rattlesnakes are found on the Monument, and rough terrain exists everywhere, but most trails are well-maintained. Winter cross-country skiing is occasionally possible on trails such as the Liberty Cap Trail.

Serpents Trail, perhaps the most popular, follows the route of the original road to the top of the Monument. This trail is accessible by parking lots at both ends, both located off Rim Rock Drive. Serpents Trail provides views of both the Monument itself and the Grand Valley below. One of the shortest trails, also popular, is Devil's Kitchen. The trailhead is located near the eastern entrance of the park on Rim Rock Drive. This trail is about 1 mile long, and ends in a sandstone grotto.

Liberty Cap trail starts from the valley floor and climbs to the rim of the Monument. Liberty Cap itself is an ancient sand dune, and provides a beautiful view of the Grand Valley. Corkscrew Trail, closed for many years but reopened in mid-2006, branches off the Liberty Cap and skirts a small canyon and cliffs that cannot be seen from the valley floor. This trail, the only loop trail on the Monument, is about 3 miles long and features a less rigorous climb than Liberty Cap.

Monument Canyon trail follows Monument Canyon for about 5 miles. This trail is often hiked up-and-back, and provides close-up views of Independence Monument, the Colorado National Monument's most distinct feature, as well as a formation named Kissing Couple.[10] The lower trailhead is accessible from CO 340 (Broadway).

No Thoroughfare Trail starts at the bottom of No Thoroughfare Canyon, near the east entrance. As the name implies, there is no official trail to the top of this canyon. The dead-end trail goes a few miles into the canyon, and up-and-back hiking is required. Some hikers have found a way to get through the entire canyon, but after a certain point the trail becomes difficult and unmarked. No Thoroughfare Canyon does have small waterfalls during the spring runoff, but is dry for most of the year.

Colorado National Monument was rated in 2017 as the best campsite in Colorado in a 50-state survey conducted by Msn.com.[11]

Historic preservation

[edit]Many of the early visitor facilities at Colorado National Monument were designed by the National Park Service and constructed by the Public Works Administration and the Civilian Conservation Corps. Several of these areas have been placed on the National Register of Historic Places in recognition of this and in consequence of their adherence to the National Park Service Rustic design standards of the time. The entire Rim Rock Drive is a National Historic District, as well as the Serpents Trail, the Devils Kitchen Picnic Shelter, and three places in the Saddlehorn area: the Saddlehorn Caretaker's House and Garage, Saddlehorn Comfort Station, and the Saddlehorn Utility Area Historic District. The Visitor Center complex is also included as an example of the Mission 66 program.

Geology

[edit]The park's geologic record preserves three different groups of rock and sediment. The oldest rocks are Early to Middle Proterozoic gneiss and schist, including the Ute Canyon Stock. Overlying these, and separated by an angular unconformity, are mostly horizontally bedded Mesozoic sedimentary rocks, including the cliff-forming Wingate Sandstone. Overlying these are various types of Quaternary unconsolidated deposits such as alluvium, colluvium, and dunes. The sedimentary rocks are folded into monoclines by several faults, including the Redlands Thrust Fault.[12]

Gallery

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Listing of acreage – December 31, 2011" (XLSX). Land Resource Division, National Park Service. Retrieved May 13, 2012. (National Park Service Acreage Reports)

- ^ "NPS Annual Recreation Visits Report". National Park Service. Retrieved April 9, 2018.

- ^ Colorado Division of Wildlife. http://wildlife.state.co.us/Education/TeacherResources/ColoradoWildlifeCompany/ColoradoNatlMonument.htm Archived 2011-07-18 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 8-03-09

- ^ Brachfeld, Aaron (September 2015). "Sunset for Colorado National Monument?". the Meadowlark Herald. No. September. the Meadowlark Herald. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ^ Museum of Western Colorado. Grand Valley History, History Timeline. "History Timeline". Archived from the original on May 1, 2009. Retrieved August 3, 2009.. Accessed 8-03-09

- ^

This article incorporates public domain material from Biophysical Description of Colorado National Monument. U.S. National Park Service. June 5, 2018. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

This article incorporates public domain material from Biophysical Description of Colorado National Monument. U.S. National Park Service. June 5, 2018. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

- ^ Lohman, S. W. (1981). "USGS: Geological Survey Bulletin 1508 (History of the Monument)". National Park Service. Archived from the original on September 10, 2020. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

- ^ a b "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Colorado NM, CO". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ^ "NOAA Online Weather Data – NWS Grand Junction". National Weather Service. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ^ "Monument Canyon Trail to Independence Monument in Colorado National Monument". hikespeak.com. Hikespeak Colorado. Retrieved May 11, 2017.

- ^ "The best campsite in every state". Msn.com. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved June 8, 2017.

- ^ Scott, R.B., Harding, A.E., Hood, W.C., Cole, R.D., Livaccari, R.F., Johnson, J.B., Shroba, R.R. and Dickerson, R.P., 2001, Geologic map of the Colorado National Monument and adjacent areas, Mesa County, Colorado: U.S. Geological Survey, Geologic Investigations Series Map I-2740, scale 1:24000. [1]