TRIPS Agreement

| Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights | |

|---|---|

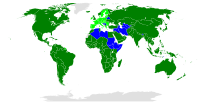

WTO members (where the TRIPS agreement applies) WTO and European Union members WTO observers | |

| Type | Annex to the Agreement establishing the World Trade Organization |

| Signed | 15 April 1994[1] |

| Location | Marrakesh, Morocco[1] |

| Effective | 1 January 1995[2] |

| Parties | 164 (All WTO members)[3] |

| Languages | English, French and Spanish |

| Full text | |

The Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) is an international legal agreement between all the member nations of the World Trade Organization (WTO). It establishes minimum standards for the regulation by national governments of different forms of intellectual property (IP) as applied to nationals of other WTO member nations.[4] TRIPS was negotiated at the end of the Uruguay Round of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) between 1989 and 1990[5] and is administered by the WTO.

The TRIPS agreement introduced intellectual property law into the multilateral trading system for the first time and remains the most comprehensive multilateral agreement on intellectual property to date. In 2001, developing countries, concerned that developed countries were insisting on an overly narrow reading of TRIPS, initiated a round of talks that resulted in the Doha Declaration. The Doha declaration is a WTO statement that clarifies the scope of TRIPS, stating for example that TRIPS can and should be interpreted in light of the goal "to promote access to medicines for all."

Specifically, TRIPS requires WTO members to provide copyright rights, covering authors and other copyright holders, as well as holders of related rights, namely performers, sound recording producers and broadcasting organisations; geographical indications; industrial designs; integrated circuit layout-designs; patents; new plant varieties; trademarks; trade names and undisclosed or confidential information, including trade secrets and test data. TRIPS also specifies enforcement procedures, remedies, and dispute resolution procedures. Protection and enforcement of all intellectual property rights shall meet the objectives to contribute to the promotion of technological innovation and to the transfer and dissemination of technology, to the mutual advantage of producers and users of technological knowledge and in a manner conducive to social and economic welfare, and to a balance of rights and obligations.

Background and history

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2012) |

TRIPS was negotiated during the Uruguay Round of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1986–1994. Its inclusion was the culmination of a program of intense lobbying by the United States by the International Intellectual Property Alliance, supported by the European Union, Japan and other developed nations.[6] Campaigns of unilateral economic encouragement under the Generalized System of Preferences and coercion under Section 301 of the Trade Act played an important role in defeating competing policy positions that were favored by developing countries like Brazil, but also including Thailand, India and Caribbean Basin states. In turn, the US strategy of linking trade policy to intellectual property standards can be traced back to the entrepreneurship of senior management at Pfizer in the early 1980s, who mobilized corporations in the United States and made maximizing intellectual property privileges the number one priority of trade policy in the United States (Braithwaite and Drahos, 2000, Chapter 7).[7]

Unlike other agreements on intellectual property, TRIPS has a powerful enforcement mechanism. States can be disciplined through the WTO's dispute settlement mechanism.

Requirements

[edit]TRIPS requires member states to provide strong protection for intellectual property rights. For example, under TRIPS:

- Copyright terms must extend at least 50 years, unless based on the life of the author. (Art. 12 and 14)[8]

- Copyright must be granted automatically, and not based upon any "formality", such as registrations, as specified in the Berne Convention. (Art. 9)

- Computer programs must be regarded as "literary works" under copyright law and receive the same terms of protection.

- National exceptions to copyright (such as "fair use" in the United States) are constrained by the Berne three-step test.

- Patents must be granted for "inventions" in all "fields of technology" provided they meet all other patentability requirements (although exceptions for certain public interests are allowed (Art. 27.2 and 27.3)[9] and must be enforceable for at least 20 years (Art 33).

- Exceptions to exclusive rights must be limited, provided that a normal exploitation of the work (Art. 13) and normal exploitation of the patent (Art 30) is not in conflict.

- No unreasonable prejudice to the legitimate interests of the right holders of computer programs and patents is allowed.

- Legitimate interests of third parties have to be taken into account by patent rights (Art 30).

- In each state, intellectual property laws may not offer any benefits to local citizens which are not available to citizens of other TRIPS signatories under the principle of national treatment (with certain limited exceptions, Art. 3 and 5).[10] TRIPS also has a most favored nation clause.

The TRIPS Agreement incorporates by reference the provisions on copyright from the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works (Art 9), with the exception of moral rights. It also incorporated by reference the substantive provisions of the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property (Art 2.1). The TRIPS Agreement specifically mentions that software and databases are protected by copyright, subject to originality requirement (Art 10).

Article 10 of the Agreement stipulates:

- Computer programs, whether in source or object code, shall be protected as literary works under the Berne Convention (1971).

- Compilations of data or other material, whether in machine readable or other form, which by reason of the selection or arrangement of their contents constitute intellectual creations shall be protected as such. Such protection, which shall not extend to the data or material itself, shall be without prejudice to any copyright subsisting in the data or material itself.

Implementation in developing countries

[edit]The obligations under TRIPS apply equally to all member states; however, developing countries were allowed extra time to implement the applicable changes to their national laws, in two tiers of transition according to their level of development. The transition period for developing countries expired in 2005. The transition period for least developed countries to implement TRIPS was extended to 2013, and until 1 January 2016 for pharmaceutical patents, with the possibility of further extension.[11]

It has therefore been argued that the TRIPS standard of requiring all countries to create strict intellectual property systems will be detrimental to poorer countries' development.[12][13] It has been argued that it is, prima facie, in the strategic interest of most if not all underdeveloped nations to use the flexibility available in TRIPS to legislate the weakest IP laws possible.[14]

This has not happened in most cases. A 2005 report by the WHO found that many developing countries have not incorporated TRIPS flexibilities (compulsory licensing, parallel importation, limits on data protection, use of broad research and other exceptions to patentability, etc.) into their legislation to the extent authorized under Doha.[15] This is likely caused by the lack of legal and technical expertise needed to draft legislation that implements flexibilities, which has often led to developing countries directly copying developed country IP legislation,[16][17] or relying on technical assistance from the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), which, according to critics such as Cory Doctorow, encourages them to implement stronger intellectual property monopolies.

Banerjee and Nayak[18] shows that TRIPS has a positive effect on R&D expenditure of Indian pharmaceutical firms.

Post-TRIPS expansion

[edit]In addition to the baseline intellectual property standards created by the TRIPS agreement, many nations have engaged in bilateral agreements to adopt a higher standard of protection. These collection of standards, known as TRIPS+ or TRIPS-Plus, can take many forms.[19] General objectives of these agreements include:

- The creation of anti-circumvention laws to protect digital rights management systems. This was achieved through the 1996 World Intellectual Property Organization Copyright Treaty (WIPO Treaty) and the WIPO Performances and Phonograms Treaty.

- More stringent restrictions on compulsory licenses for patents.

- More aggressive patent enforcement. This effort has been observed more broadly in proposals for WIPO and European Union rules on intellectual property enforcement. The 2001 EU Copyright Directive was to implement the 1996 WIPO Copyright Treaty.

- The campaign for the creation of a WIPO Broadcasting Treaty that would give broadcasters (and possibly webcasters) exclusive rights over the copies of works they have distributed.

Panel reports

[edit]According to WTO 10th Anniversary, Highlights of the first decade, Annual Report 2005 page 142,[20] in the first ten years, 25 complaints have been lodged leading to the panel reports and appellate body reports on TRIPS listed below.[21]

- 2005 Panel Report:[22]

- European Communities – Protection of Trademarks and Geographical Indications for Agricultural Products and Foodstuffs.

- 2000 Panel Report:[23] Part 2[24] and 2000 Appellate Body Report[25]

- Canada – Term of Patent Protection.

- 2000 Panel Report, Part 1:[26] and Part 2[27]

- United States – Section 110(5) of the US Copyright Act.

- 2000 Panel Report:[28]

- Canada – Patent Protection of Pharmaceutical Products.

- 2001 Panel Report:[29] and 2002 Appellate Body Report[30]

- United States – Section 211 Omnibus Appropriations Act of 1998.

- 1998 Panel Report:[31]

- India – Patent Protection for Pharmaceutical and Agricultural Chemical Products.

- 1998 Panel Report:[32]

- Indonesia – Certain Measures Affecting the Automobile Industry.

Criticism

[edit]TRIPs imposed on the entire world the dominant intellectual property regime in the United States and Europe, as it is today. I believe that the way that intellectual property regime has evolved is not good for the United States and the EU; but even more, I believe it is not in the interest of the developing countries.

Since TRIPS came into force, it has been subject to criticism from developing countries, academics, and non-governmental organizations. Though some of this criticism is against the WTO generally, many advocates of trade liberalisation also regard TRIPS as poor policy. TRIPS's wealth concentration effects (moving money from people in developing countries to copyright and patent owners in developed countries), and its imposition of artificial scarcity on the citizens of countries that would otherwise have had weaker intellectual property laws, are common bases for such criticisms. Other criticism has focused on the failure of TRIPS to accelerate investment and technology flows to low-income countries, a benefit advanced by WTO members in the lead-up to the agreement's formation. Statements by the World Bank indicate that TRIPS has not led to a demonstrable acceleration of investment to low-income countries, though it may have done so for middle-income countries.[33]

Daniele Archibugi and Andrea Filippetti have argued that the main motive for TRIPS was a decline in the competitiveness of the technology industry in the United States, Japan, and the European Union against emerging markets, which it largely failed to abate. They instead argue that the main supporters and beneficiaries of TRIPS were IP-intensive multinational corporations in these countries, and that TRIPS enabled them to outsource key operations to emerging markets.[6]

Archibugi and Filippetti also argue that the importance of TRIPS, and intellectual property in general, in the process of generation and diffusion of knowledge and innovation has been overestimated by its supporters.[6] This point has been supported by United Nations findings indicating many countries with weak protection routinely benefit from strong levels of foreign direct investment (FDI).[34] Analysis of OECD countries in the 1980s and 1990s (during which the patent life of drugs was extended by six years) showed that while total number of products registered increased slightly, the mean innovation index remained unchanged.[35] In contrast to that, Jörg Baten, Nicola Bianchi and Petra Moser (2017) find historical evidence that under certain circumstances compulsory licensing – a key mechanism to weaken intellectual property rights that is covered by Article 31 of the TRIPS – may indeed be effective in promoting invention by increasing the threat of competition in fields with low pre-existing levels of competition. They argue, however, that the benefits from weakening intellectual property rights strongly depend on whether the governments can credibly commit to using it only in exceptional cases of emergencies since firms may invest less in R&D if they expect repeated episodes of compulsory licensing.[36]

TRIPS-plus conditions mandating standards beyond TRIPS have also been the subject of scrutiny.[37] These FTA agreements contain conditions that limit the ability of governments to introduce competition for generic producers. In particular, the United States has been criticised for advancing protection well beyond the standards mandated by TRIPS. The United States Free Trade Agreements with Australia, Morocco and Bahrain have extended patentability by requiring patents be available for new uses of known products.[38] The TRIPS agreement allows the grant of compulsory licenses at a nation's discretion. TRIPS-plus conditions in the United States' FTAs with Australia, Jordan, Singapore and Vietnam have restricted the application of compulsory licenses to emergency situations, antitrust remedies, and cases of public non-commercial use.[38]

Access to essential medicines

[edit]The most visible conflict has been over AIDS drugs in Africa. Despite the role that patents have played in maintaining higher drug costs for public health programs across Africa, this controversy has not led to a revision of TRIPS. Instead, an interpretive statement, the Doha Declaration, was issued in November 2001, which indicated that TRIPS should not prevent states from dealing with public health crises and allowed for compulsory licenses. After Doha, PhRMA, the United States and to a lesser extent other developed nations began working to minimize the effect of the declaration.[39]

In 2001, at the Fourth Ministerial Conference in Doha, several World Trade Organization (WTO) members proposed changes to Articles 27 and 31 of the TRIPS Agreement, aiming to strike a balance between patent protection for pharmaceuticals and the impact of such protection on drug prices. This initiative led to the Doha Declaration, which reaffirmed the sovereign right of WTO members to grant compulsory licenses for pharmaceuticals. The Declaration also acknowledged the struggles faced by countries with limited pharmaceutical manufacturing capabilities in utilizing compulsory licensing under TRIPS, signaling perceived limitations within the original TRIPS framework. Following two years of intense negotiations, the TRIPS Council responded by implementing the Waiver Decision in 2003, which temporarily allowed WTO members to grant compulsory licenses free from the restrictions of TRIPS Articles 31(f) and 31(h). The principles of this decision were later codified into TRIPS through the Amendment Protocol of 2005, which introduced Article 31bis, effectively becoming law in 2017 post-ratification by two-thirds of WTO members.

Article 31bis allows a WTO member with insufficient or no manufacturing capacities in the pharmaceutical sector (the "Importing State") to import patented pharmaceutical products produced under a special export compulsory license granted by another WTO member (the "Exporting State"). It is structured as a dialogical interaction between an Importing State and an Exporting State and has specific procedural requirements. The Exporting State can issue an export compulsory license exempt from Article 31(f) restrictions, but the license must comply with several specific terms. Developed WTO members can opt-out from being Importing States, but the COVID-19 pandemic revealed the potential shortfalls of this decision as several developed countries struggled with inadequate vaccine production capabilities.[40]

In 2003, the US Bush administration changed its position, concluding that generic treatments might in fact be a component of an effective strategy to combat HIV.[41] Bush created the PEPFAR program, which received $15 billion from 2003 to 2007, and was reauthorized in 2008 for $48 billion over the next five years. Despite wavering on the issue of compulsory licensing, PEPFAR began to distribute generic drugs in 2004–05.

In 2020, conflicts re-emerged over patents, copyrights and trade secrets related to COVID-19 vaccines, diagnostics and treatments. South Africa and India proposed that WTO grant a temporary waiver to enable more widespread production of the vaccines, since suppressing the virus as quickly as possible benefits the entire world.[42][43] The waivers would be in addition to the existing, but cumbersome, flexibilities in TRIPS allowing countries to impose compulsory licenses.[44][45] Over 100 developing nations supported the waiver but it was blocked by the G7 members.[46] This blocking was condemned by 400 organizations including Doctors Without Borders and 115 members of the European Parliament.[47] In June 2022, after extensive involvement of the European Union, the WTO instead adopted a watered-down agreement that focuses only on vaccine patents, excludes high-income countries and China, and contains few provisions that are not covered by existing flexibilities.[48][49]

Software and business method patents

[edit]Another controversy has been over the TRIPS Article 27 requirements for patentability "in all fields of technology", and whether or not this necessitates the granting of software and business method patents.

See also

[edit]Related treaties and laws

[edit]- Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement (ACTA)

- EU Directive on the enforcement of intellectual property rights (IPRED)

- Patent Law Treaty (PLT)

- Substantive Patent Law Treaty (SPLT)

- Uruguay Round Agreement Act of the United States (URAA)

Related organizations

[edit]Other

[edit]- Confusing similarity

- Geographical indication

- Intellectual property in the People's Republic of China

- Japanese Sound Recording Trade Disputes

- List of international trade topics

- List of parties to international copyright agreements

- World Trade Organization Dispute 160

References

[edit]- ^ a b "TRIPS Agreement (as amended on 23 January 2017)". World Trade Organization. Archived from the original on 18 October 2020. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ "WTO – intellectual property – overview of TRIPS Agreement". World Trade Organization. Archived from the original on 25 February 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ "WTO TRIPS implementation". International Intellectual Property Alliance. Archived from the original on 1 June 2012. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ^ See TRIPS Art. 1(3).

- ^ Gervais, Daniel (2012). The TRIPS Agreement: Negotiating History. London: Sweet & Maxwell. pp. Part I.

- ^ a b c Archibugi, D.; Filippetti, A. (2010). "The globalization of intellectual property rights: Four learned lessons and four thesis" (PDF). Journal of Global Policy. 1 (2): 137–149. doi:10.1111/j.1758-5899.2010.00019.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 July 2011.

- ^ Sell, Susan K. (2003). Private Power, Public Law: The Globalization of Intellectual Property Rights. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511491665. ISBN 978-0-521-81914-5.

- ^ "intellectual property (TRIPS) – agreement text – standards". WTO. 15 April 1994. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ World Trade Organization, "Part II — Standards concerning the availability, scope and use of Intellectual Property Rights; Sections 5 and 6", Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, archived from the original on 22 June 2017, retrieved 21 December 2005

- ^ World Trade Organization, "Part I — General Provisions and Basic Principles", Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, archived from the original on 12 November 2020, retrieved 28 February 2006

- ^ "WTO – intellectual property (TRIPS) – frequently-asked questions". World Trade Organization. Archived from the original on 28 May 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ IP Justice policy paper for the WIPO development agenda, IP Justice, archived from the original on 8 January 2013

- ^ J.-F. Morin; R. Gold (2014). "An Integrated Model of Legal Transplantation: The Diffusion of Intellectual Property Law in Developing Countries" (PDF). International Studies Quarterly. 58 (4): 781–792. doi:10.1111/isqu.12176. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 September 2018. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

- ^ Blouin, Chantal; Heymann, Jody; Drager, Nick (2007). Trade and Health. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 33. ISBN 9780773532816. JSTOR j.ctt812g5.

- ^ Musungu, Sisule F.; Oh, Cecilia (August 2005), The use of flexibilities in TRIPS by developing countries: can they promote access to medicines?, Commission on Intellectual Property Rights, Innovation and Public Health (CIPIH), archived from the original on 31 October 2013, retrieved 5 October 2020

- ^ Finger, J. Michael (2000). "The WTO's special burden on less developed countries" (PDF). Cato Journal. 19 (3). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 July 2006.

- ^ J.-F. Morin; M. Bourassa. "Pharmaceutical patent policy in developing countries: learning from the Canadian experience". Intellectual Property, Pharmaceuticals and Public Health.

- ^ Banerjee, Tannista; Nayak, Arnab (14 March 2014). "Effects of Trade Related Intellectual Property Rights on the research and development expenditure of Indian pharmaceutical industry". Journal of Pharmaceutical Health Services Research. 5 (2): 89–94. doi:10.1111/jphs.12050. S2CID 70896207.

- ^ Jean-Frederic Morin and Dimitri Theriault, How Trade Deals Extend the Frontiers of International Patent Law Archived 6 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine, CIGI Paper 199, 2018; Overview of "TRIPS-Plus" Standards – Oxford Scholarship. Oxford University Press. 2011. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195390124.003.0009. ISBN 978-0-19-989453-6. Archived from the original on 4 July 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- ^ World Trade Organization (2005). "Annual Report 2005" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 July 2005. Retrieved 20 July 2005.

- ^ "Index of disputes issues". World Trade Organisation. Archived from the original on 13 February 2015. Retrieved 14 August 2021.

- ^ "2005 News items – Panel reports out on geographical indications disputes". WTO. 15 March 2005. Archived from the original on 10 June 2005. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ^ "CANADA – TERM OF PATENT PROTECTION : Report of the Panel" (PDF). World Trade Organization. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 September 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ "ATTACHMENT 1.1 : FIRST SUBMISSION OF THE UNITED STATES" (PDF). World Trade Organization. 18 November 1999. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 September 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ "CANADA – TERM OF PATENT PROTECTION" (PDF). World Trade Organization. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 September 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ "UNITED STATES – SECTION 110(5) OF THE US COPYRIGHT ACT" (PDF). World Trade Organization. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 September 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ "UNITED STATES – SECTION 110(5) OF US COPYRIGHT ACT : Request for the Establishment of a Panel by the European Communities and their Member States" (PDF). World Trade Organization. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 September 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ "WorldTradeLaw.net" (PDF). Worldtradelaw.net. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 May 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ "United States – Section 211 Omnibus Appropriations Act of 1998" (PDF). World Trade Organization. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 September 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ "UNITED STATES – SECTION 211 OMNIBUS APPROPRIATIONS ACT OF 1998" (PDF). World Trade Organization. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 September 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ "WorldTradeLaw.net" (PDF). Worldtradelaw.net. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 May 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ "WorldTradeLaw.net" (PDF). Worldtradelaw.net. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 May 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ Xiong, Ping (2012b). "Patents in TRIPS-Plus Provisions and the Approaches to Interpretation of Free Trade Agreements and TRIPS: Do They Affect Public Health?". Journal of World Trade. 46 (1): 155. doi:10.54648/TRAD2012006.

- ^ Collins-Chase, Charles (Spring 2008). "The Case against TRIPS-Plus Protection in Developing Countries Facing AIDs Epidemics". University of Pennsylvania Journal of International Law. 29 (3). Archived from the original on 7 June 2015. Retrieved 23 June 2015.

- ^ Troullier, Patrice; et al. (22 June 2002). "Drug development for neglected diseases: a deficient market and a public-health policy failure". The Lancet. 359 (9324): 2188–2194. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09096-7. hdl:10144/28441. PMID 12090998. S2CID 1616485.

- ^ Baten, Jörg; Bianchi, Nicola; Moser, Petra (2017). "Compulsory licensing and innovation–Historical evidence from German patents after WWI". Journal of Development Economics. 126: 231–242. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2017.01.002.

- ^ Morin, Jean-Frederic (2006). "Tripping up TRIPs Debate: IP and Health" (PDF). International Journal of Intellectual Property Management. 1 (1/2): 37–53. doi:10.1504/IJIPM.2006.011021. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 December 2017.

- ^ a b Newfarmer, Richard (2006). Trade, Doha, and Development (1st ed.). The World Bank. p. 292.

- ^ Timmermann, Cristian; Henk van den Belt (2013). "Intellectual property and global health: from corporate social responsibility to the access to knowledge movement". Liverpool Law Review. 34 (1): 47–73. doi:10.1007/s10991-013-9129-9. S2CID 145492036. Archived from the original on 23 June 2020. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ Tosato, Andrea; Igbokwe, Ezinne (January 2023). "Access to Medicines and Pharmaceutical Patents: Fulfilling the Promise of TRIPS Article 31bis". Fordham Law Review. 91 (5): 1791. Retrieved 23 July 2023.

- ^ Morin, Jean-Frederic (2011). "The Life-Cycle of Transnational Issues: Lessons from the Access to Medicines Controversy" (PDF). Global Society. 25 (2): 227–247. doi:10.1080/13600826.2011.553914. S2CID 216592972. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 December 2018.

- ^ Nebehay, Emma Farge, Stephanie (10 December 2020). "WTO delays decision on waiver on COVID-19 drug, vaccine rights". Reuters. Archived from the original on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Members to continue discussion on proposal for temporary IP waiver in response to COVID-19". World Trade Organisation. Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ Baker, Brook K.; Labonte, Ronald (9 January 2021). "Dummy's guide to how trade rules affect access to COVID-19 vaccines". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 23 February 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ "An Unnecessary Proposal: A WTO Waiver of Intellectual Property Rights for COVID-19 Vaccines". Cato Institute. 16 December 2020. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ "G7 leaders are shooting themselves in the foot by failing to tackle global vaccine access". Amnesty International. 19 February 2021. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- ^ Pietromarchi, Virginia (1 March 2021). "Patently unfair: Can waivers help solve COVID vaccine inequality?". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 26 April 2021.

- ^ "TRIPS Waiver | Covid-19 Response". covid19response.org.

- ^ "WTO finally agrees on a TRIPS deal. But not everyone is happy". Devex. 17 June 2022.

Sources

[edit]- Braithwaite and Drahos, Global Business Regulation, Cambridge University Press, 2000

- Westkamp, 'TRIPS Principles, Reciprocity and the Creation of Sui-Generis-Type Intellectual Property Rights for New Forms of Technology' [2003] 6(6) The Journal of World Intellectual Property 827–859, ISSN 1422-2213

- Banerjee and Nayak, 'Effects of trade related intellectual property rights on the research and development expenditure of Indian pharmaceutical industry' [2014] 5 Journal of Pharmaceutical Health Services Research 89–94.

- Azam, M. (2016). Intellectual Property and Public Health in the Developing World. Open Book Publishers. doi:10.11647/OBP.0093. ISBN 978-1-78374-228-8. A free textbook for download.

External links

[edit]- TRIPS agreement (PDF version)

- Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (html version)

- World Trade Organization links

- Audio presentation by Professor Susan Sell, George Washington University, on intellectual property rights in the global context. Archived 26 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- WTO TRIPS Agreement profile on database of Market Governance Mechanisms

- Intellectual property law of the European Union

- Intellectual property treaties

- World Trade Organization agreements

- Copyright treaties

- Patent law treaties

- Treaties concluded in 1994

- Treaties entered into force in 1996

- Treaties of Albania

- Treaties of Angola

- Treaties of Antigua and Barbuda

- Treaties of Argentina

- Treaties of Armenia

- Treaties of Australia

- Treaties of Austria

- Treaties of Bahrain

- Treaties of Bangladesh

- Treaties of Barbados

- Treaties of Belgium

- Treaties of Belize

- Treaties of Benin

- Treaties of Bolivia

- Treaties of Botswana

- Treaties of Brazil

- Treaties of Brunei

- Treaties of Bulgaria

- Treaties of Burkina Faso

- Treaties of Burundi

- Treaties of Cambodia

- Treaties of Cameroon

- Treaties of Canada

- Treaties of Cape Verde

- Treaties of the Central African Republic

- Treaties of Chad

- Treaties of Chile

- Treaties of the People's Republic of China

- Treaties of Colombia

- Treaties of the Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Treaties of the Republic of the Congo

- Treaties of Costa Rica

- Treaties of Ivory Coast

- Treaties of Croatia

- Treaties of Cuba

- Treaties of Cyprus

- Treaties of the Czech Republic

- Treaties of Denmark

- Treaties of Djibouti

- Treaties of Dominica

- Treaties of the Dominican Republic

- Treaties of Ecuador

- Treaties of Egypt

- Treaties of El Salvador

- Treaties of Estonia

- Treaties entered into by the European Union

- Treaties of Fiji

- Treaties of Finland

- Treaties of France

- Treaties of Gabon

- Treaties of the Gambia

- Treaties of Georgia (country)

- Treaties of Germany

- Treaties of Ghana

- Treaties of Greece

- Treaties of Grenada

- Treaties of Guatemala

- Treaties of Guinea

- Treaties of Guinea-Bissau

- Treaties of Haiti

- Treaties of Honduras

- Treaties of Hong Kong

- Treaties of Hungary

- Treaties of Iceland

- Treaties of India

- Treaties of Indonesia

- Treaties of Israel

- Treaties of Italy

- Treaties of Jamaica

- Treaties of Japan

- Treaties of Jordan

- Treaties of Kazakhstan

- Treaties of Kenya

- Treaties of South Korea

- Treaties of Kuwait

- Treaties of Kyrgyzstan

- Treaties of Laos

- Treaties of Latvia

- Treaties of Lesotho

- Treaties of Liechtenstein

- Treaties of Lithuania

- Treaties of Luxembourg

- Treaties of Macau

- Treaties of North Macedonia

- Treaties of Madagascar

- Treaties of Malaysia

- Treaties of Malawi

- Treaties of the Maldives

- Treaties of Mali

- Treaties of Malta

- Treaties of Mauritania

- Treaties of Mauritius

- Treaties of Mexico

- Treaties of Moldova

- Treaties of Mongolia

- Treaties of Montenegro

- Treaties of Morocco

- Treaties of Mozambique

- Treaties of Myanmar

- Treaties of Namibia

- Treaties of Nepal

- Treaties of the Netherlands

- Treaties of New Zealand

- Treaties of Nicaragua

- Treaties of Niger

- Treaties of Nigeria

- Treaties of Norway

- Treaties of Oman

- Treaties of Pakistan

- Treaties of Panama

- Treaties of Papua New Guinea

- Treaties of Paraguay

- Treaties of Peru

- Treaties of the Philippines

- Treaties of Poland

- Treaties of Portugal

- Treaties of Qatar

- Treaties of Romania

- Treaties of Russia

- Treaties of Rwanda

- Treaties of Saint Kitts and Nevis

- Treaties of Saint Lucia

- Treaties of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

- Treaties of Samoa

- Treaties of Saudi Arabia

- Treaties of Senegal

- Treaties of Seychelles

- Treaties of Sierra Leone

- Treaties of Singapore

- Treaties of Slovakia

- Treaties of Slovenia

- Treaties of the Solomon Islands

- Treaties of South Africa

- Treaties of Spain

- Treaties of Sri Lanka

- Treaties of Suriname

- Treaties of Eswatini

- Treaties of Sweden

- Treaties of Switzerland

- Treaties of Taiwan

- Treaties of Tajikistan

- Treaties of Tanzania

- Treaties of Thailand

- Treaties of Togo

- Treaties of Tonga

- Treaties of Trinidad and Tobago

- Treaties of Tunisia

- Treaties of Turkey

- Treaties of Uganda

- Treaties of Ukraine

- Treaties of the United Arab Emirates

- Treaties of the United Kingdom

- Treaties of the United States

- Treaties of Uruguay

- Treaties of Vanuatu

- Treaties of Venezuela

- Treaties of Vietnam

- Treaties of Yemen

- Treaties of Zambia

- Treaties of Zimbabwe

- Treaties of Liberia

- Treaties of Azerbaijan