Taiwan

Taiwan,[II][i] officially the Republic of China (ROC),[I][j] is a country[27] in East Asia.[m] The main island of Taiwan, also known as Formosa, lies between the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northeast, and the Philippines to the south. It has an area of 35,808 square kilometres (13,826 square miles), with mountain ranges dominating the eastern two-thirds and plains in the western third, where its highly urbanized population is concentrated. The combined territories under ROC control consist of 168 islands[n] in total covering 36,193 square kilometres (13,974 square miles).[17][39] The largest metropolitan area is formed by Taipei (the capital), New Taipei City, and Keelung. With around 23.9 million inhabitants, Taiwan is among the most densely populated countries.

Taiwan has been settled for at least 25,000 years. Ancestors of Taiwanese indigenous peoples settled the island around 6,000 years ago. In the 17th century, large-scale Han Chinese immigration began under a Dutch colony and continued under the Kingdom of Tungning, the first predominantly Han Chinese state in Taiwanese history. The island was annexed in 1683 by the Qing dynasty of China and ceded to the Empire of Japan in 1895. The Republic of China, which had overthrown the Qing in 1912 under the leadership of Sun Yat-sen, took control following the surrender of Japan in 1945. The immediate resumption of the Chinese Civil War resulted in the loss of the Chinese mainland to Communist forces, who established the People's Republic of China and the flight of the ROC central government to Taiwan in 1949. The effective jurisdiction of the ROC has since been limited to Taiwan, Penghu, and smaller islands.

The early 1960s saw rapid economic growth and industrialization called the "Taiwan Miracle".[40] In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the ROC transitioned from a one-party state under martial law to a multi-party democracy, with democratically elected presidents beginning in 1996. Taiwan's export-oriented economy is the 21st-largest in the world by nominal GDP and the 20th-largest by PPP measures, with a focus on steel, machinery, electronics, and chemicals manufacturing. Taiwan is a developed country.[41][42] It is ranked highly in terms of civil liberties,[43] healthcare,[44] and human development.[h][22]

The political status of Taiwan is contentious.[49] Despite being a founding member, the ROC no longer represents China as a member of the United Nations after UN members voted in 1971 to recognize the PRC instead.[50] The ROC maintained its claim of being the sole legitimate representative of China and its territory until 1991, when it ceased to regard the Chinese Communist Party as a rebellious group and acknowledged its control over mainland China.[51] Taiwan is claimed by the PRC, which refuses to establish diplomatic relations with countries that recognise the ROC. Taiwan maintains official diplomatic relations with 11 out of 193 UN member states and the Holy See.[52] Many others maintain unofficial diplomatic ties through representative offices and institutions that function as de facto embassies and consulates. International organizations in which the PRC participates either refuse to grant membership to Taiwan or allow it to participate on a non-state basis. Domestically, the major political contention is between parties favoring eventual Chinese unification and promoting a pan-Chinese identity, contrasted with those aspiring to formal international recognition and promoting a Taiwanese identity; in the 21st century, both sides have moderated their positions to broaden their appeal.[53][54]

Etymology

Names for the island

In his Daoyi Zhilüe (1349), Wang Dayuan used "Liuqiu" as a name for the island, or the part of it closest to Penghu.[55] Elsewhere, the name was used for the Ryukyu Islands in general or Okinawa specifically; the name Ryūkyū is the Japanese form of Liúqiú. The name also appears in the Book of Sui (636) and other early works, but scholars cannot agree on whether these references are to the Ryukyus, Taiwan or even Luzon.[56]

The name Formosa (福爾摩沙) dates from 1542, when Portuguese sailors noted it on their maps as Ilha Formosa (Portuguese for "beautiful island").[57][58] The name Formosa eventually "replaced all others in European literature"[59] and remained in common use among English speakers into the 20th century.[60]

In 1603, a Chinese expedition fleet anchored at a place in Taiwan called Dayuan, a variant of "Taiwan".[61][62][63] In the early 17th century, the Dutch East India Company established a commercial post at Fort Zeelandia (modern-day Anping) on a coastal sandbar called "Tayouan",[64] after their ethnonym for a nearby Taiwanese aboriginal tribe, possibly Taivoan people.[65] This name was also adopted into the Chinese vernacular as the name of the sandbar and nearby area (Tainan). The modern word "Taiwan" is derived from this usage, which is written in different transliterations (大員,大圓,大灣,臺員,臺圓 or 臺窩灣) in Chinese historical records. The area occupied by modern-day Tainan was the first permanent settlement by both European colonists and Chinese immigrants. The settlement grew to be the island's most important trading center and served as its capital until 1887.

Use of the current Chinese name (臺灣 / 台灣) became official as early as 1684 during the Qing dynasty with the establishment of Taiwan Prefecture centered in modern-day Tainan. Through its rapid development the entire Taiwanese mainland eventually became known as "Taiwan".[66][67][68][69]

Names of the country and jurisdiction

The official name of the country in English is the "Republic of China". Shortly after the ROC's establishment in 1912, while it was still located on the Chinese mainland, the government used the short form "China" (Zhōngguó, 中國) to refer to itself, derived from zhōng ("central" or "middle") and guó ("state, nation-state").[o] The term developed under the Zhou dynasty in reference to its royal demesne,[p] and was then applied to the area around Luoyi (present-day Luoyang) during the Eastern Zhou and later to China's Central Plain, before being used as an occasional synonym for the state during the Qing era.[71] The name of the republic had stemmed from the party manifesto of the Tongmenghui in 1905, which says the four goals of the Chinese revolution was "to expel the Manchu rulers, to revive Chunghwa, to establish a Republic, and to distribute land equally among the people."[III] Revolutionary leader Sun Yat-sen proposed the name Chunghwa Minkuo as the assumed name of the new country when the revolution succeeded.

During the 1950s and 1960s, after the ROC government had withdrawn to Taiwan, it was commonly referred to as "Nationalist China" (or "Free China") to differentiate it from "communist China" (or "Red China").[73] Over subsequent decades, the Republic of China has become commonly known as "Taiwan", after the main island. To avoid confusion, the ROC government in Taiwan began to put "Taiwan" next to its official name in 2005.[74] In ROC government publications, the name is written as "Republic of China (Taiwan)", "Republic of China/Taiwan", or sometimes "Taiwan (ROC)".[75][76][77]

"Taiwan Area" was defined to mean the island of Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen, Matsu, and other territory under ROC's effective control,[78] in contrast to "Mainland Area" which refers to ROC territory outside the Taiwan Area and under Chinese Communist control.[79]

The Republic of China participates in most international forums and organizations under the name "Chinese Taipei" as a compromise with the People's Republic of China (PRC). For instance, it is the name under which it has participated in the Olympic Games as well as the APEC.[80] "Taiwan authorities" is sometimes used by the PRC to refer to the government in Taiwan.[81]

History

Pre-colonial period

Taiwan was joined to the Asian mainland in the Late Pleistocene, until sea levels rose about 10,000 years ago.[82] Human remains and Paleolithic artifacts dated 20,000 to 30,000 years ago have been found.[83][84] Study of the human remains suggested they were Australo-Papuan people similar to Negrito populations in the Philippines.[85] Paleolithic Taiwanese likely settled the Ryukyu Islands 30,000 years ago.[86] Slash-and-burn agriculture practices started at least 11,000 years ago.[87]

Stone tools of the Changbin culture have been found in Taitung and Eluanbi. Archaeological remains suggest they were initially hunter-gatherers that slowly shifted to intensive fishing.[88][89] The distinct Wangxing culture, found in Miaoli County, were initially gatherers who shifted to hunting.[90]

Around 6,000 years ago, Taiwan was settled by farmers of the Dapenkeng culture, most likely from what is now southeast China.[91] These cultures are the ancestors of modern Taiwanese Indigenous peoples and the originators of the Austronesian language family.[92][93] Trade with the Philippines persisted from the early 2nd millennium BCE, including the use of Taiwanese jade in the Philippine jade culture.[94][95]

The Dapenkeng culture was succeeded by a variety of cultures throughout the island, including the Tahu and Yingpu; the Yuanshan were characterized by rice harvesting. Iron appeared in such cultures as the Niaosung culture, influenced by trade with China and Maritime Southeast Asia.[96][97] The Plains Indigenous peoples mainly lived in permanent walled villages, with a lifestyle based on agriculture, fishing, and hunting.[98] They had traditionally matriarchal societies.[98]

Early colonial period (to 1683)

The Penghu Islands were inhabited by Han Chinese fishermen by 1171, and in 1225 Penghu was attached to Jinjiang.[99][100][101][102] The Yuan dynasty officially incorporated Penghu under the jurisdiction of Tong'an County in 1281.[102] Penghu was evacuated in the 15th century by the Ming dynasty as part of their maritime ban, which lasted until the late 16th century.[103] In 1349, Wang Dayuan provided the first written account of a visit to Taiwan.[104][105] By the 1590s, a small number of Chinese from Fujian had started cultivating land in southwestern Taiwan.[106] Some 1,500-2,000 Chinese lived or stayed temporarily on the southern coast of Taiwan, mostly for seasonal fishing but also subsistence farming and trading, by the early 17th century.[107][105] In 1603, Chen Di visited Taiwan on an anti-wokou expedition and recorded an account of the Taiwanese Indigenous people.[62]

In 1591, Japan sent envoys to deliver a letter requesting tribute relations with Taiwan. They found no leader to deliver the letter to and returned home. In 1609, a Japanese expedition was sent to survey Taiwan. After being attacked by the Indigenous people, they took some prisoners and returned home. In 1616, a Japanese fleet of 13 ships were sent to Taiwan. Due to a storm, only one ship made it there and is presumed to have returned to Japan.[108][109]

In 1624, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) established Fort Zeelandia on the coastal islet of Tayouan (in modern Tainan).[110][69] The lowland areas were occupied by 11 Indigenous chiefdoms, some of which fell under Dutch control, including the Kingdom of Middag.[69][111] When the Dutch arrived, southwestern Taiwan was already frequented by a mostly transient Chinese population numbering close to 1,500.[107] The VOC encouraged Chinese farmers to immigrate and work the lands under Dutch control and by the 1660s, some 30,000 to 50,000 Chinese were living on the island.[112][113] Most of the farmers cultivated rice for local consumption and sugar for export while some immigrants engaged in deer hunting for export.[114][115][116]

In 1626, the Spanish Empire occupied northern Taiwan as a trading base, first at Keelung and in 1628 building Fort Santo Domingo at Tamsui.[117][118] This colony lasted until 1642, when the last Spanish fortress fell to Dutch forces.[119] The Dutch then marched south, subduing hundreds of villages in the western plains.[119]

Following the fall of the Ming dynasty in Beijing in 1644, Koxinga (Zheng Chenggong) pledged allegiance to the Yongli Emperor and attacked the Qing dynasty along the southeastern coast of China.[120] In 1661, under increasing Qing pressure, he moved his forces from his base in Xiamen to Taiwan, expelling the Dutch the following year. The Dutch retook the northern fortress at Keelung in 1664, but left the island in 1668 in the face of indigenous resistance.[121][122]

The Zheng regime, known as the Kingdom of Tungning, proclaimed its loyalty to the overthrown Ming, but ruled independently.[123][124][125][126] However, Zheng Jing's return to China to participate in the Revolt of the Three Feudatories paved the way for the Qing invasion and occupation of Taiwan in 1683.[127][128]

Qing rule (1683–1895)

Following the defeat of Koxinga's grandson by an armada led by Admiral Shi Lang in 1683, the Qing dynasty formally annexed Taiwan in May 1684, making it a prefecture of Fujian province while retaining its administrative seat (now Tainan) under Koxinga as the capital.[129][130][131]

The Qing government generally tried to restrict migration to Taiwan throughout the duration of its administration because it believed that Taiwan could not sustain too large a population without leading to conflict. After the defeat of the Kingdom of Tungning, most of its population in Taiwan was sent back to the mainland, leaving the official population count at only 50,000, including 10,000 troops. Despite official restrictions, officials in Taiwan solicited settlers from the mainland, causing tens of thousands of annual arrivals by 1711. A permit system was officially recorded in 1712, but it likely existed as early as 1684; its restrictions included only allowing those to enter who had property on the mainland, family in Taiwan, and who were not accompanied by wives or children. Many of the male migrants married local Indigenous women. Over the 18th century, restrictions were relaxed. In 1732, families were allowed to move to Taiwan.[132][133] By 1811, there were more than two million Han settlers in Taiwan, and profitable sugar and rice production industries provided exports to the mainland.[134][135][136] In 1875, restrictions on entering Taiwan were repealed.[137]

Three counties nominally covered the entire western plains, but actual control was restricted to a smaller area. A government permit was required for settlers to go beyond the Dajia River. Qing administration expanded across the western plains area over the 18th century due to continued illegal crossings and settlement.[138] The Taiwanese Indigenous peoples were categorized by the Qing administration into acculturated aborigines who had adopted Han culture and non-acculturated aborigines who had not. The Qing did little to administer or subjugate them. When Taiwan was annexed, there were 46 aboriginal villages under its control, likely inherited from the Kingdom of Tungning. During the early Qianlong period there were 93 acculturated villages and 61 non-acculturated villages that paid taxes. In response to the Zhu Yigui settler rebellion in 1722, separation of aboriginals and settlers became official policy via 54 stelae used to mark the frontier boundary. The markings were changed four times over the latter half of the 18th century due to continued settler encroachment. Two aboriginal affairs sub-prefects, one for the north and one for the south, were appointed in 1766.[139]

During the 200 years of Qing rule in Taiwan, the Plains Indigenous peoples rarely rebelled against the government and the mountain Indigenous peoples were left to their own devices until the last 20 years of Qing rule. Most of the more than 100 rebellions during the Qing period, such as the Lin Shuangwen rebellion, were caused by Han settlers.[140][141] Their frequency was evoked by the common saying "every three years an uprising, every five years a rebellion" (三年一反、五年一亂), primarily in reference to the period between 1820 and 1850.[142][143][144]

Many officials stationed in Taiwan called for an active colonization policy over the 19th century. In 1788, Taiwan Prefect Yang Tingli supported the efforts of a settler named Wu Sha to claim land held by the Kavalan people. In 1797, Wu Sha was able to recruit settlers with financial support from the local government but was unable to officially register the land. In the early 1800s, local officials convinced the emperor to officially incorporate the area by playing up the issue of piracy if the land was left alone.[145] In 1814, some settlers attempted to colonize central Taiwan by fabricating rights to lease aboriginal land. They were evicted by government troops two years later. Local officials continued to advocate for the colonization of the area but were ignored.[146]

The Qing took on a more active colonization policy after 1874 when Japan invaded Indigenous territory in southern Taiwan and the Qing government was forced to pay an indemnity for them to leave.[147] The administration of Taiwan was expanded with new prefectures, sub-prefectures, and counties. Mountain roads were constructed to make inner Taiwan more accessible. Restrictions on entering Taiwan were ended in 1875 and agencies for recruiting settlers were established on the mainland, but efforts to promote settlement ended soon after.[148] In 1884, Keelung in northern Taiwan was occupied during the Sino-French War but the French forces failed to advance any further inland while their victory at Penghu in 1885 resulted in disease and retreat soon afterward as the war ended. Colonization efforts were renewed under Liu Mingchuan. In 1887, Taiwan's status was upgraded to a province. Taipei became the permanent capital in 1893. Liu's efforts to increase revenues on Taiwan's produce were hampered by foreign pressure not to increase levies. A land reform was implemented, increasing revenue which still fell short of expectation.[149][150][151] Modern technologies such as electric lighting, a railway, telegraph lines, steamship service, and industrial machinery were introduced under Liu's governance, but several of these projects had mixed results. A campaign to formally subjugate the Indigenous peoples ended with the loss of a third of the army after fierce resistance from the Mkgogan and Msbtunux peoples. Liu resigned in 1891 due to criticism of these costly projects.[152][153][129][154]

By the end of the Qing period, the western plains were fully developed as farmland with about 2.5 million Chinese settlers. The mountainous areas were still largely autonomous under the control of Indigenous peoples. Indigenous land loss under the Qing occurred at a relatively slow pace due to the absence of state-sponsored land deprivation for the majority of Qing rule.[155][156]

Japanese rule (1895–1945)

Following the Qing defeat in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), Taiwan, its associated islands, and the Penghu archipelago were ceded to Japan by the Treaty of Shimonoseki.[157] Inhabitants wishing to remain Qing subjects had to move to mainland China within a two-year grace period, which few saw as feasible.[158] Estimates say around 4,000 to 6,000 departed before the expiration of the grace period, and 200,000 to 300,000 followed during the subsequent disorder.[159][135][160] On 25 May 1895, a group of pro-Qing high officials proclaimed the Republic of Formosa to resist impending Japanese rule. Japanese forces entered the capital at Tainan and quelled this resistance on 21 October 1895.[161] About 6,000 inhabitants died in the initial fighting and some 14,000 died in the first year of Japanese rule. Another 12,000 "bandit-rebels" were killed from 1898 to 1902.[162][163][164] Subsequent rebellions against the Japanese (the Beipu uprising of 1907, the Tapani incident of 1915, and the Musha incident of 1930) were unsuccessful but demonstrated opposition to Japanese rule.

The colonial period was instrumental to the industrialization of the island, with its expansion of railways and other transport networks, the building of an extensive sanitation system, the establishment of a formal education system, and an end to the practice of headhunting.[165][166] The resources of Taiwan were used to aid the development of Japan. The production of cash crops such as sugar greatly increased, and large areas were therefore diverted from the production of rice.[167] By 1939, Taiwan was the seventh-greatest sugar producer in the world.[168]

The Han and Indigenous populations were classified as second- and third-class citizens, and many prestigious government and business positions were closed to them.[169] After suppressing Han guerrillas in the first decade of their rule, Japanese authorities engaged in bloody campaigns against the Indigenous people residing in mountainous regions, culminating in the Musha Incident of 1930.[170] Intellectuals and laborers who participated in left-wing movements were also arrested and massacred (e.g. Chiang Wei-shui and Masanosuke Watanabe).[171] Around 1935, the Japanese began an island-wide assimilation project.[172] Chinese-language newspapers and curriculums were abolished. Taiwanese music and theater were outlawed. A national Shinto religion was promoted in parallel with the suppression of traditional Taiwanese beliefs. Starting from 1940, families were also required to adopt Japanese surnames, although only 2% had done so by 1943.[172] By 1938, 309,000 Japanese were residing in Taiwan.[173]

During the Second World War, the island was developed into a naval and air base while its agriculture, industry, and commerce suffered.[174][175] Air attacks and the subsequent invasion of the Philippines were launched from Taiwan. The Imperial Japanese Navy operated heavily from Taiwanese ports, and its think tank "South Strike Group" was based at Taihoku Imperial University. Military bases and industrial centers, such as Kaohsiung and Keelung, became targets of heavy Allied bombings, which destroyed many of the factories, dams, and transport facilities built by the Japanese.[176][175] In October 1944, the Formosa Air Battle was fought between American carriers and Japanese forces in Taiwan. Over 200,000 of Taiwanese served in the Japanese military, with over 30,000 casualties.[177] Over 2,000 women, euphemistically called "comfort women", were forced into sexual slavery for Imperial Japanese troops.[178]

After Japan's surrender, most Japanese residents were expelled.[179]

Republic of China (1945–present)

While Taiwan was under Japanese rule, the Republic of China was founded on mainland China on 1 January 1912 following the Xinhai Revolution of 1911.[180] Central authority waxed and waned in response to warlordism (1915–28), Japanese invasion (1937–45), and the Chinese Civil War (1927–49), with central authority strongest during the Nanjing decade (1927–37), when most of China came under the control of the Kuomintang (KMT).[181] During World War II, the 1943 Cairo Declaration specified that Formosa and the Pescadores be returned by Japan to the ROC;[182][183] the terms were later repeated in the 1945 Potsdam Declaration[184] that Japan agreed to carry out in its instrument of surrender.[185][186] On 25 October 1945, Japan surrendered Taiwan to the ROC, and in the Treaty of San Francisco, Japan formally renounced their claims to the islands, though without specifying to whom they were surrendered.[187][188][189][190][q] In the same year, Japan and the ROC signed a peace treaty.[191]

While initially enthusiastic about the return of Chinese administration and the Three Principles of the People, Formosans grew increasingly dissatisfied about being excluded from higher positions, the postponement of local elections even after the enactment of a constitution on the mainland, the smuggling of valuables off the island, the expropriation of businesses into government-operated monopolies, and the hyperinflation of 1945–1949.[192][193][194][195] The shooting of a civilian on 28 February 1947 triggered island-wide unrest, which was suppressed with military force in what is now called the February 28 Incident.[196][197] Mainstream estimates of the number killed range from 18,000 to 30,000.[198][199][200] Chen was later replaced by Wei Tao-ming, who made an effort to undo previous mismanagement by re-appointing a good proportion of islanders and re-privatizing businesses.[201]

After the end of World War II, the Chinese Civil War resumed. A series of Chinese Communist offensives in 1949 led to the capture of its capital Nanjing on 23 April and the subsequent defeat of the Nationalists on the mainland. The Communists founded the People's Republic of China on 1 October.[202] On 7 December 1949, Chiang Kai-Shek evacuated his Nationalist government to Taiwan and made Taipei the temporary capital of the ROC.[203] Some 2 million people, mainly soldiers, members of the ruling Kuomintang and intellectual and business elites, were evacuated to Taiwan, adding to the earlier population of approximately six million. These people and their descendants became known in Taiwan as "waisheng ren" (外省人). The ROC government took to Taipei many national treasures and much of China's gold and foreign currency reserves.[204][205][206] Most of the gold was used to pay soldiers' salaries,[207] with some used to issue the New Taiwan dollar, part of a price stabilization program to slow inflation in Taiwan.[208][209]

After losing control of mainland China in 1949, the ROC retained control of Taiwan and Penghu (Taiwan, ROC), parts of Fujian (Fujian, ROC)—specifically Kinmen, Wuqiu (now part of Kinmen) and the Matsu Islands and two major islands in the South China Sea. The ROC also briefly retained control of the entirety of Hainan, parts of Zhejiang (Chekiang)—specifically the Dachen Islands and Yijiangshan Islands—and portions of Tibet, Qinghai, Xinjiang and Yunnan. The Communists captured Hainan in 1950, captured the Dachen Islands and Yijiangshan Islands during the First Taiwan Strait Crisis in 1955 and defeated the ROC revolts in Northwest China in 1958. ROC forces entered Burma and Thailand in the 1950s and were defeated by Communists in 1961. Since losing control of mainland China, the Kuomintang continued to claim sovereignty over 'all of China', which it defined to include mainland China (including Tibet), Taiwan (including Penghu), Outer Mongolia, and other minor territories.

Martial law era (1949–1987)

Martial law, declared on Taiwan in May 1949,[210] continued to be in effect until 1987,[210][211] and was used to suppress political opposition. During the White Terror, as the period is known, 140,000 people were imprisoned or executed for being perceived as anti-KMT or pro-Communist.[212] Many citizens were arrested, tortured, imprisoned or executed for their real or perceived link to the Chinese Communist Party. Since these people were mainly from the intellectual and social elite, an entire generation of political and social leaders was destroyed.

Following the eruption of the Korean War, US President Harry S. Truman dispatched the United States Seventh Fleet into the Taiwan Strait to prevent hostilities between the ROC and the PRC.[213] The United States also passed the Sino-American Mutual Defense Treaty and the Formosa Resolution of 1955, granting substantial foreign aid to the KMT regime between 1951 and 1965.[214] The US foreign aid stabilized prices in Taiwan by 1952.[215] The KMT government instituted many laws and land reforms that it had never effectively enacted on mainland China.[216] Economic development was encouraged by American aid and programs such as the Joint Commission on Rural Reconstruction, which turned the agricultural sector into the basis for later growth. Under the combined stimulus of the land reform and the agricultural development programs, agricultural production increased at an average annual rate of 4 percent from 1952 to 1959.[217] The government also implemented a policy of import substitution industrialization, attempting to produce imported goods domestically.[218] The policy promoted the development of textile, food, and other labor-intensive industries.[219]

As the Chinese Civil War continued, the government built up military fortifications throughout Taiwan. Veterans built the Central Cross-Island Highway through the Taroko Gorge in the 1950s. During the Second Taiwan Strait Crisis in 1958, Nike Hercules missiles were added to the formation of missile batteries throughout the island.[220][221]

During the 1960s and 1970s, the ROC maintained an authoritarian, single-party government under the Kuomintang's Dang Guo system while its economy became industrialized and technology-oriented.[222] This rapid economic growth, known as the Taiwan Miracle, occurred following a strategy of prioritizing agriculture, light industries, and heavy industries, in that order.[223] Export-oriented industrialization was achieved by tax rebate for exports, removal of import restriction, moving from multiple exchange rate to single exchange rate system, and depreciation of the New Taiwan dollar.[224] Infrastructure projects such as the Sun Yat-sen Freeway, Taoyuan International Airport, Taichung Harbor, and Jinshan Nuclear Power Plant were launched, while the rise of steel, petrochemical, and shipbuilding industries in southern Taiwan saw the transformation of Kaohsiung into a special municipality on par with Taipei.[225] In the 1970s, Taiwan became the second fastest growing economy in Asia.[226] Real growth in GDP averaged over 10 percent.[227] In 1978, the combination of tax incentives and a cheap, well-trained labor force attracted investments of over $1.9 billion from overseas Chinese, the United States, and Japan.[228] By 1980, foreign trade reached $39 billion per year and generated a surplus of $46.5 million.[223] Along with Hong Kong, Singapore, and South Korea, Taiwan became known as one of the Four Asian Tigers.

Because of the Cold War, most Western nations and the United Nations regarded the ROC as the sole legitimate government of China until the 1970s. Eventually, especially after Taiwan's expulsion from the United Nations, most nations switched diplomatic recognition to the PRC. Until the 1970s, the ROC government was regarded by Western critics as undemocratic for upholding martial law, severely repressing any political opposition, and controlling the media. The KMT did not allow the creation of new parties and competitive democratic elections did not exist.[229][230][231][232][233]

From the late 1970s to the 1990s, Taiwan underwent political and social reforms that transformed it into a democracy.[234][235] Chiang Ching-kuo, Chiang Kai-shek's son, served as premier from 1972 and rose to the presidency in 1978. He sought to move more authority to "bensheng ren" (residents of Taiwan before Japan's surrender and their descendants).[236] Pro-democracy activists Tangwai emerged as the opposition. In 1979, the Kaohsiung Incident took place in Kaohsiung on Human Rights Day. Although the protest was rapidly crushed by the authorities, it is considered as the main event that united Taiwan's opposition.[237]

In 1984, Chiang Ching-kuo selected Lee Teng-hui as his vice-president. After the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was (illegally) founded as the first opposition party in Taiwan to counter the KMT in 1986, Chiang announced that he would allow the formation of new parties.[238] On 15 July 1987, Chiang lifted martial law on the main island of Taiwan.[239][240]

Transition to democracy

After Chiang Ching-kuo's death in 1988, Lee Teng-hui became the first president of the ROC born in Taiwan.[241] Lee's administration oversaw a period of democratization in which the Temporary Provisions against the Communist Rebellion were abolished and the Additional Articles of the Constitution were introduced.[242][243] Congressional representation was allocated to only the Taiwan Area,[244] and Taiwan underwent a process of localization in which Taiwanese culture and history were promoted over a pan-China viewpoint[245] while assimilationist policies were replaced with support for multiculturalism.[246] In 1996, Lee was re-elected in the first direct presidential election.[247] During Lee's administration, both he and his party were involved in corruption controversies that came to be known as "black gold" politics.[248][249][250]

Chen Shui-bian of the DPP was elected as the first non-KMT president in 2000.[251] However, Chen lacked legislative majority. The opposition KMT developed the Pan-Blue Coalition with other parties, mustering a slim majority over the DPP-led Pan-Green Coalition.[252] Polarized politics emerged in Taiwan with the Pan-Blue preference for eventual Chinese unification, while the Pan-Green prefers Taiwanese independence.

Chen's reference to "One Country on Each Side" of the Taiwan Strait undercut cross-Strait relations in 2002.[253] He pushed for the first national referendum on cross-Strait relations,[254][255] and called for an end to the National Unification Council.[256] State-run companies began dropping "China" references in their names and including "Taiwan".[257] In 2008, referendums asked whether Taiwan should join the UN.[258] This act alienated moderate constituents who supported the status quo, as well as those with cross-strait economic ties. It also created tension with the mainland and disagreements with the United States.[259] Chen's administration was also dogged by public concerns over reduced economic growth, legislative gridlock, and corruption investigations.[260][261][259]

The KMT's nominee Ma Ying-jeou won the 2008 presidential election on a platform of increased economic growth and better ties with the PRC under a policy of "mutual non-denial".[258] Under Ma, Taiwan and China opened up direct flights and cargo shipments.[262] The PRC government even made the atypical decision to not demand that Taiwan be barred from the annual World Health Assembly.[263] Ma also made an official apology for the White Terror.[264][265] However, closer economic ties with China raised concerns about its political consequences.[266][267] In 2014, university students occupied the Legislative Yuan and prevented the ratification of the Cross-Strait Service Trade Agreement in what became known as the Sunflower Student Movement. The movement gave rise to youth-based third parties such as the New Power Party, and is viewed to have contributed to the DPP's victories in the 2016 presidential and legislative elections,[268] the latter of which resulted in the first DPP legislative majority in Taiwanese history.[269] In January 2024, William Lai Ching-te of the ruling Democratic Progressive Party won Taiwan's presidential elections.[270] However, no party won a majority in the simultaneous Taiwan's legislative election for the first time since 2004, meaning 51 seats for the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), 52 seats for the Kuomintang (KMT), and the Taiwan People's Party (TPP) secured eight seats.[271]

Geography

The land controlled by the ROC consists of 168 islands[n] with a combined area of 36,193 square kilometres (13,974 sq mi).[17][39][i] The main island, known historically as Formosa, makes up 99 percent of this area, measuring 35,808 square kilometres (13,826 sq mi) and lying some 180 kilometres (112 mi) across the Taiwan Strait from the southeastern coast of mainland China. The East China Sea lies to its north, the Philippine Sea to its east, the Luzon Strait directly to its south and the South China Sea to its southwest. Smaller islands include the Penghu Islands in the Taiwan Strait, the Kinmen, Matsu and Wuqiu islands near the Chinese coast, and some of the South China Sea islands.

The main island is a tilted fault block, characterized by the contrast between the eastern two-thirds, consisting mostly of five rugged mountain ranges parallel to the east coast, and the flat to gently rolling plains of the western third, where the majority of Taiwan's population reside. There are several peaks over 3,500 metres, the highest being Yu Shan at 3,952 m (12,966 ft), making Taiwan the world's fourth-highest island. The tectonic boundary that formed these ranges is still active, and the island experiences many earthquakes. There are also many active submarine volcanoes in the Taiwan Strait.

Taiwan contains four terrestrial ecoregions: Jian Nan subtropical evergreen forests, South China Sea Islands, South Taiwan monsoon rain forests, and Taiwan subtropical evergreen forests.[272] The eastern mountains are heavily forested and home to a diverse range of wildlife, while land use in the western and northern lowlands is intensive. The country had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 6.38/10, ranking it 76th globally out of 172 countries.[273]

Climate

Taiwan lies on the Tropic of Cancer, and its general climate is marine tropical.[14] The northern and central regions are subtropical, whereas the south is tropical and the mountainous regions are temperate.[274] The average rainfall is 2,600 millimetres (100 inches) per year for the island proper; the rainy season is concurrent with the onset of the summer East Asian Monsoon in May and June.[275] The entire island experiences hot, humid weather from June through September. Typhoons are most common in July, August and September.[275] During the winter (November to March), the northeast experiences steady rain, while the central and southern parts of the island are mostly sunny.

Due to climate change, the average temperature in Taiwan has risen 1.4 °C (2.5 °F) in the last 100 years, twice the worldwide temperature rise.[276] The goal of the Taiwanese government is to cut carbon emissions by 20 percent in 2030 and by 50 percent in 2050, compared to 2005 levels. Carbon emissions increased by 0.92 percent between 2005 and 2016.[277]

Geology

The island of Taiwan lies in a complex tectonic area between the Yangtze Plate to the west and north, the Okinawa Plate on the north-east, and the Philippine Mobile Belt on the east and south. The upper part of the crust on the island is primarily made up of a series of terranes, mostly old island arcs which have been forced together by the collision of the forerunners of the Eurasian Plate and the Philippine Sea Plate. These have been further uplifted as a result of the detachment of a portion of the Eurasian Plate as it was subducted beneath remnants of the Philippine Sea Plate, a process which left the crust under Taiwan more buoyant.[278]

The east and south of Taiwan are a complex system of belts formed by, and part of the zone of, active collision between the North Luzon Trough portion of the Luzon Volcanic Arc and South China, where accreted portions of the Luzon Arc and Luzon forearc form the eastern Coastal Range and parallel inland Longitudinal Valley of Taiwan, respectively.[279]

The major seismic faults in Taiwan correspond to the various suture zones between the various terranes. These have produced major quakes. On 21 September 1999, a 7.3 quake known as the "921 earthquake" killed more than 2,400 people. The seismic hazard map for Taiwan by the USGS shows 9/10 of the island at the most hazardous rating.[280]

Government and politics

Government

The government of the Republic of China was founded on the 1947 Constitution of the ROC and its Three Principles of the People, which states that the ROC "shall be a democratic republic of the people, to be governed by the people and for the people".[281] It underwent significant revisions in the 1990s, known collectively as the Additional Articles. The government is divided into five branches (Yuan): the Executive Yuan (cabinet), the Legislative Yuan (Congress or Parliament), the Judicial Yuan, the Control Yuan (audit agency), and the Examination Yuan (civil service examination agency).

The head of state and commander-in-chief of the armed forces is the president, who is elected by popular vote for a maximum of 2 four-year terms on the same ticket as the vice-president. The president appoints the members of the Executive Yuan as their cabinet, including a premier, who is officially the President of the Executive Yuan; members are responsible for policy and administration.[281]

The main legislative body is the unicameral Legislative Yuan with 113 seats. Seventy-three are elected by popular vote from single-member constituencies; thirty-four are elected based on the proportion of nationwide votes received by participating political parties in a separate party list ballot; and six are elected from two three-member aboriginal constituencies. Members serve four-year terms. Originally the unicameral National Assembly, as a standing constitutional convention and electoral college, held some parliamentary functions, but the National Assembly was abolished in 2005 with the power of constitutional amendments handed over to the Legislative Yuan and all eligible voters of the Republic via referendums.[281][282]

The premier is selected by the president without the need for approval from the legislature, and neither the president nor the premier wields veto power.[281] Historically, the ROC has been dominated by strongman single party politics. This legacy has resulted in executive powers currently being concentrated in the office of the president rather than the premier.[283]

The Judicial Yuan is the highest judicial organ. It interprets the constitution and other laws and decrees, judges administrative suits, and disciplines public functionaries. The president and vice-president of the Judicial Yuan and additional thirteen justices form the Council of Grand Justices.[284] They are nominated and appointed by the president, with the consent of the Legislative Yuan. The highest court, the Supreme Court, consists of a number of civil and criminal divisions, each of which is formed by a presiding judge and four associate judges, all appointed for life. In 1993, a separate constitutional court was established to resolve constitutional disputes, regulate the activities of political parties and accelerate the democratization process. There is no trial by jury but the right to a fair public trial is protected by law and respected in practice; many cases are presided over by multiple judges.[281]

The Control Yuan is a watchdog agency that monitors the actions of the executive. It can be considered a standing commission for administrative inquiry, like the Court of Auditors of the European Union or the Government Accountability Office of the United States.[281] It is also responsible for the National Human Rights Commission.

The Examination Yuan is in charge of validating the qualification of civil servants. It is based on the imperial examination system used in dynastic China. It can be compared to the European Personnel Selection Office of the European Union or the Office of Personnel Management of the United States.[281] It was downsized in 2019, and there have been calls for its abolition.[285][286]

Constitution

The constitution was drafted by the KMT while the ROC still governed the Chinese mainland.[287] Political reforms beginning in the late 1970s resulted in the end of martial law in 1987, and Taiwan transformed into a multiparty democracy in the early 1990s. The constitutional basis for this transition to democracy was gradually laid in the Additional Articles of the Constitution. These articles suspended portions of the Constitution designed for the governance of mainland China and replacing them with articles adapted for the governance of and guaranteeing the political rights of residents of the Taiwan Area, as defined in the Act Governing Relations between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area.[288]

National boundaries were not explicitly prescribed by the 1947 Constitution, and the Constitutional Court declined to define these boundaries in a 1993 interpretation, viewing the question as a political question to be resolved by the Executive and Legislative Yuans.[289] The 1947 Constitution included articles regarding representatives from former Qing dynasty territories including Tibet and Mongol banners.[290][291][292] The ROC recognized Mongolia as an independent country in 1946 after signing the 1945 Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship and Alliance, but after retreating to Taiwan in 1949 it reneged to preserve its claim over mainland China.[293] The Additional Articles of the 1990s did not alter national boundaries, but suspended articles regarding Mongolian and Tibetan representatives. The ROC began to accept the Mongolian passport and removed clauses referring to Outer Mongolia from the Act Governing Relations between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area in 2002.[294] In 2012 the Mainland Affairs Council issued a statement clarifying that Outer Mongolia was not part of the ROC's national territory in 1947.[295] The Mongolian and Tibetan Affairs Commission in the Executive Yuan was abolished in 2017.

Major camps

Taiwan's political scene is divided into two major camps in terms of cross-Strait relations, i.e. how Taiwan should relate to China or the PRC. The Pan-Green Coalition (e.g. the Democratic Progressive Party) leans pro-independence, and the Pan-Blue Coalition (e.g. the Kuomintang) leans pro-unification.[296] Moderates in both camps regard the Republic of China as a sovereign independent state, but the Pan-Green Coalition regard the ROC as synonymous with Taiwan,[297] while moderates in the Pan-Blue Coalition view it as synonymous with China.[298] These positions formed against the backdrop of the PRC's Anti-Secession Law, which threatens the use of "non-peaceful means" to respond to formal Taiwanese independence.[299] The ROC government has understood this to mean a military invasion of Taiwan.[300]

The Pan-Green Coalition is mainly led by the pro-independence Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), Taiwan Statebuilding Party (TSP) and Green Party (GPT). They oppose the idea that Taiwan is part of China, and seek wide diplomatic recognition and an eventual declaration of formal Taiwan independence.[301] In September 2007, the then ruling DPP approved a resolution asserting separate identity from China and called for the enactment of a new constitution for a "normal country". It called also for general use of "Taiwan" as the country's name, without abolishing its formal name, the "Republic of China".[302] The name "Taiwan" has been used increasingly often after the emergence of the Taiwanese independence movement.[259] Some members of the coalition, such as former President Chen Shui-bian, argue that it is unnecessary to proclaim independence because "Taiwan is already an independent, sovereign country" and the Republic of China is the same as Taiwan.[303] Despite being a member of KMT prior to and during his presidency, Lee Teng-hui also held a similar view and was a supporter of the Taiwanization movement.[304] TSP and GPT[305] have adopted a line that aggressive route more than the DPP, in order to win over pro-independence voters who are dissatisfied with the DPP's conservative stance.

The Pan-Blue Coalition, composed of the pro-unification Kuomintang (KMT), People First Party (PFP) and New Party generally support the spirit of the 1992 Consensus, where the KMT claimed that there is one China, but that the ROC and PRC have different interpretations of what "China" means. They favor eventual unification with China.[306] Regarding independence, the mainstream Pan-Blue position is to maintain the status quo, while refusing immediate unification.[307][308] President Ma Ying-jeou stated that there will be no unification nor declaration of independence during his presidency.[309][310] Some Pan-Blue members seek to improve relationships with PRC, with a focus on improving economic ties.[311]

National identity

Roughly 84 percent of Taiwan's population are descendants of Han Chinese immigrants between 1683 and 1895. Another significant fraction descends from Han Chinese who immigrated from mainland China in the late 1940s and early 1950s. The shared cultural origin as well as hostility between the rival ROC and PRC have resulted in national identity being a contentious issue with political overtones.

Since democratic reforms and the lifting of martial law, a distinct Taiwanese identity is often at the heart of political debates. Its acceptance makes the island distinct from mainland China, and therefore may be seen as a step towards forming a consensus for de jure Taiwan independence.[313] The Pan-Green camp supports a predominantly Taiwanese identity (although "Chinese" may be viewed as cultural heritage), while the Pan-Blue camp supports a predominantly Chinese identity (with "Taiwanese" as a regional/diasporic Chinese identity).[306] The KMT has downplayed this stance in the recent years and now supports a Taiwanese identity as part of a Chinese identity.[314][315]

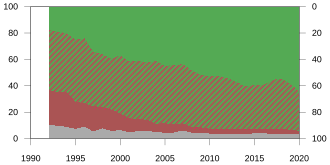

Taiwanese identification has increased substantially since the early 1990s, while Chinese identification has fallen to a low level, and identification as both has also seen a reduction. In 1992, 17.6 percent of respondents identified as Taiwanese, 25.5 percent as Chinese, 46.4 percent as both, and 10.5 percent non-response. In June 2021, 63.3 percent identified as Taiwanese, 2.6 percent as Chinese, 31.4 percent as both, and 2.7 percent non-response.[312] A survey conducted in Taiwan by Global Views Survey Research Center in July 2009 showed that 82.8 percent of respondents consider the ROC and the PRC two separate countries with each developing on its own but 80.2 percent think they are members of the Chinese.[316]

Public opinion

Domestic public opinion has preferred maintaining the status quo, though pro-independence sentiment has steadily risen since 1994. In June 2021, an annual poll found that 28.2 percent supported the status quo and postponing a decision, 27.5 percent supported maintaining the status quo indefinitely, 25.8 percent supported the status quo with a move toward independence, 5.9 percent supported the status quo with a move toward unification, 5.7 percent gave no response, 5.6 percent supported independence as soon as possible, and 1.5 percent supported unification as soon as possible.[317] A referendum question in 2018 asked if Taiwan's athletes should compete under "Taiwan" in the 2020 Summer Olympics but did not pass; the New York Times attributed the failure to a campaign cautioning that a name change might lead to Taiwan being banned "under Chinese pressure".[318]

The KMT, the largest Pan-Blue party, supports the status quo for the indefinite future with a stated ultimate goal of unification. However, it does not support unification in the short term with the PRC as such a prospect would be unacceptable to most of its members and the public.[319] Ma Ying-jeou, chairman of the KMT and former president of the ROC, has set out democracy, economic development to a level near that of Taiwan, and equitable wealth distribution as the conditions that the PRC must fulfill for unification to occur.[320] Ma stated that the cross-Strait relations are neither between two Chinas nor two states. It is a special relationship. Further, he stated that the sovereignty issues between the two cannot be resolved at present.[321]

The Democratic Progressive Party, the largest Pan-Green party, officially seeks independence, but in practice also supports the status quo because neither independence nor unification seems likely in the short or even medium term.[322] In 2017, Taiwanese premier William Lai said that he was a "political worker who advocates Taiwan independence", but that as Taiwan was already an independent country called the Republic of China,[323][324][325][326][327] it had no need to declare independence.[328]

Foreign relations and international status

The political and legal statuses of Taiwan are contentious issues. The People's Republic of China (PRC) claims that Taiwan is Chinese territory and that the PRC replaced the ROC government in 1949, becoming the sole legal government of China.[81] The ROC, however, has its own currency, widely accepted passport, postage stamps, internet TLD, armed forces and constitution with an independently elected president.[329] It has not formally renounced its claim to the mainland, but ROC government publications have increasingly downplayed this historical claim.[330]

Until 1928, the foreign policy of Republican China was complicated by a lack of internal unity—competing centers of power all claimed legitimacy. This situation changed after the defeat of the Peiyang Government by the Kuomintang (KMT), which led to widespread diplomatic recognition of the Republic of China.[331] After the KMT retreated to Taiwan, most countries, especially those of the Western Bloc – save the United Kingdom, which recognized the PRC in 1950[332] – continued to maintain formal relations with the ROC; but recognition gradually eroded and many countries switched recognition to the People's Republic of China in the 1970s. On 25 October 1971, UN Resolution 2758 was adopted by 76 votes to 35 with 17 abstentions, recognizing the PRC as China's sole representative in the United Nations.[333][334]

The PRC refuses to have diplomatic relations with any nation that has diplomatic relations with the ROC, and requires all nations with which it has diplomatic relations to make a statement on its claims to Taiwan.[335][336] As a result, only 11 UN member states and the Holy See maintain official diplomatic relations with the Republic of China.[52] The ROC maintains unofficial relations with other countries via de facto embassies and consulates mostly called Taipei Economic and Cultural Representative Offices (TECRO), with branch offices called "Taipei Economic and Cultural Offices" (TECO). Both TECRO and TECO are "unofficial commercial entities" of the ROC in charge of maintaining diplomatic relations, providing consular services, and serving the national interests of the ROC.[337]

From 1954 to 1979, the United States was a partner with Taiwan in a mutual defense treaty. The United States remains one of the main supporters of Taiwan and, through the Taiwan Relations Act passed in 1979, has continued selling arms and providing military training to the Republic of China Armed Forces.[338] The PRC considers US involvement disruptive to the stability of the region.[339][340] The official position of the United States is that the PRC is expected to "use no force or threat[en] to use force against Taiwan" and the ROC is to "exercise prudence in managing all aspects of Cross-Strait relations." Both are to refrain from performing actions or espousing statements "that would unilaterally alter Taiwan's status".[341] While not officially classified as a major non-NATO ally, it has been de facto treated this way by the United States since at least 2003.[342]

Taiwan, since 2016 under the Tsai administration's New Southbound Policy, has pursued closer economic relations with South and Southeast Asian countries, increasing cooperation on investments and people-to-people exchanges despite the region's general lack of official diplomatic ties with Taipei.[343][344] The policy has led to Taiwan receiving an increased number of migrants and students from the region.[345] However, a few scandals of Southeast Asians, particularly Indonesians, experiencing exploitation in scholarship programs[346] and in some labor industries have emerged as setbacks for the policy[347][348] as well as for Indonesia-Taiwan relations.[349][350]

Relations with the PRC

The Mainland Affairs Council (MAC) of Taiwan is responsible for relations with the PRC, while the Taiwan Affairs Office (TAO) of the PRC is responsible for relations with Taiwan. Exchanges are conducted through private organizations both founded in 1991: the Straits Exchange Foundation (SEF) of Taiwan and the Association for Relations Across the Taiwan Straits (ARATS) of the PRC.

The PRC's One China principle states that Taiwan and mainland China are both part of China, and that the PRC is the only legitimate government of China.[50] It seeks to prevent or reduce any formal recognition of the ROC as an independent sovereign state,[351][352] meaning that Taiwan participates in many international forums as a non-state member under names such as "Chinese Taipei". The PRC suggested the "one country, two systems" employed in Hong Kong as a model for peaceful unification with Taiwan.[353][354] While it aims for peaceful reunification, the PRC does not rule out the use of force.[355][324] The political environment is complicated by the potential for military conflict[356][357][358] should events outlined in the PRC's Anti-Secession Law occur, such as Taiwan declaring de jure independence. There is a substantial military presence on the Fujian coast as well as PRC sorties into Taiwan's air defense identification zone (ADIZ).[359][360][325]

In November 1992, the ARATS and SEF held a meeting which would later become known as the 1992 Consensus. The SEF announced that both sides agreed that there was only one China, but disagreed on the definition of China (i.e. the ROC vs. PRC), while the ARATS announced that the two agreed on the One China principle, but did not mention differences regarding its definition made in the SEF statement.[361] In 2019, Tsai Ing-wen rejected the 1992 Consensus.[362] She stated that there is no need to talk about the 1992 Consensus anymore, because this term has already been defined by Beijing as "one country, two systems."[363]

Participation in international events and organizations

The ROC was a founding member of United Nations, and held the seat of China on the Security Council and other UN bodies until 1971, when it was expelled by Resolution 2758 and replaced with the PRC as the ROC now has neither official membership nor observer status in the organization. Since 1993, the ROC has petitioned the UN for entry, but its applications have not made it past committee stage.[364][365] Due to the One China policy, most UN member states, including the United States, do not wish to discuss the issue of the ROC's political status for fear of souring diplomatic ties with the PRC.[366]

The ROC government shifted its focus to organizations affiliated with the UN, as well as organizations outside the UN system.[367] The government sought to participate in the World Health Organization (WHO) since 1997,[368][369] their efforts were rejected until 2009, when they participated as an observer under the name "Chinese Taipei" after reaching an agreement with Beijing.[370][371] In 2017, Taiwan again began to be excluded from the WHO even in an observer capacity.[372] This exclusion caused a number of scandals during the COVID-19 outbreak.[373][374]

The Nagoya Resolution in 1979 approved by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) provided a compromise for the ROC to use the name "Chinese Taipei" in international events where the PRC is also a party, such as the Olympic Games.[375][376][377] Under the IOC charter, ROC flags cannot be flown at any official Olympic venue or gathering.[378] The ROC also participates in the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum (since 1991) and the World Trade Organization (since 2002) under the names "Chinese Taipei" and "Separate Customs Territory of Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen and Matsu", respectively.[379][380] It was a founding member of the Asian Development Bank, but since China's ascension in 1986 has participated under the name "Taipei, China". The ROC is able to participate as "China" in organizations in which the PRC does not participate, such as the World Organization of the Scout Movement.

Due to its limited international recognition, the Republic of China has been a member of the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization (UNPO) since the foundation of the organization in 1991, represented by a government-funded organization, the Taiwan Foundation for Democracy (TFD), under the name "Taiwan".[381][382]

Military

The Republic of China Armed Forces takes its roots in the National Revolutionary Army, which was established by Sun Yat-sen in 1924 in Guangdong with a goal of reunifying China under the Kuomintang. When the People's Liberation Army won the Chinese Civil War, much of the National Revolutionary Army retreated to Taiwan along with the government. The 1947 Constitution of the ROC reformed it into the Republic of China Armed Forces, making it the national army rather than the army of a political party. Units which surrendered and remained in mainland China were either disbanded or incorporated into the People's Liberation Army.

From 1949 to the 1970s, the primary mission of the Taiwanese military was to "retake mainland China" through Project National Glory. As this mission has transitioned away from attack because the relative strength of the PRC has massively increased, the ROC military has begun to shift emphasis from the traditionally dominant Army to the air force and navy. Control of the armed forces has also passed into the hands of the civilian government.[383][384]

The ROC began a series of force reduction plans since the 1990s to scale down its military from a level of 450,000 in 1997 to 380,000 in 2001.[385] As of 2021[update], the total strength of the Armed Forces is capped at 215,000 with 90 percent manning ratio for volunteer military.[386] Conscription remains universal for qualified males reaching age eighteen, but as a part of the reduction effort many are given the opportunity to fulfill their draft requirement through alternative service.[387] Taiwan cut compulsory military service to four months in 2013 but will extend military service to one year in 2024.[388][389] The military's reservists is around 2.5 million including first-wave reservists numbered at 300,000 as of 2022[update].[390] Taiwan's defense spending as a percentage of its GDP fell below three percent in 1999 and had been trending downwards over the first two decades of the twenty-first century.[391][392] The ROC government spent approximately two percent of GDP on defense and failed to raise the spending as high as proposed three percent of GDP.[393][394][395] In 2022, Taiwan proposed 2.4 percent of projected GDP in defense spending for the following year, continued to remain below three percent.[396]

The ROC and the United States signed the Sino-American Mutual Defense Treaty in 1954, and established the United States Taiwan Defense Command. About 30,000 US troops were stationed in Taiwan, until the United States established diplomatic relations with the PRC in 1979.[397] A significant amount of military hardware has been bought from the United States, and continues to be legally guaranteed by the Taiwan Relations Act.[338] France and the Netherlands have also sold military weapons and hardware to the ROC, but they almost entirely stopped in the 1990s under pressure of the PRC.[398][399]

There is no guarantee in the Taiwan Relations Act or any other treaty that the United States will defend Taiwan, even in the event of invasion.[400] On several occasions in 2021 and 2022, U.S. President Joe Biden stated that the United States will intervene if the PRC attempts to invade Taiwan.[401][402][403][404] However, White House officials insisted that US policy on Taiwan has not changed.[405][406] The joint declaration on security between the US and Japan signed in 1996 may imply that Japan would be involved in any response. However, Japan has refused to stipulate whether the "area surrounding Japan" mentioned in the pact includes Taiwan.[407] The Australia, New Zealand, United States Security Treaty (ANZUS Treaty) may mean that other US allies, such as Australia, could be involved.[408][409] While this would risk damaging economic ties with China,[410] a conflict over Taiwan could lead to an economic blockade of China by a greater coalition.[411][412][413][414][415]

LGBT rights

On 24 May 2017, the Constitutional Court ruled that then-current marriage laws had been violating the Constitution by denying same-sex couples the right to marry. The Court ruled that if the Legislative Yuan did not pass adequate amendments to Taiwanese marriage laws within two years, same-sex marriages would automatically become lawful in Taiwan.[416] In a referendum question in 2018, however, voters expressed overwhelming opposition to same-sex marriage and supported the removal of content about homosexuality from primary school textbooks. According to the New York Times, the referendum questions were subject to a "well-funded and highly organized campaign led by conservative Christians and other groups" involving the use of misinformation.[318] Nevertheless, the vote against same-sex marriage does not affect the court ruling, and on 17 May 2019, Taiwan's parliament approved a bill legalizing same-sex marriage, making it the first country in Asia to do so.[417][418][419]

Taiwan has an annual pride event, Taiwan Pride. It currently holds the record for the largest LGBT gathering in East Asia, rivaling Tel Aviv Pride in Israel.[420] The event draws more than 200,000 people.[421]

Administrative divisions

According to the 1947 constitution, the territory of the ROC is according to its "existing national boundaries".[422] The ROC is, de jure constitutionally, divided into provinces, special municipalities (which are further divided into districts for local administration), and the province-level Tibet Area. Each province is subdivided into cities and counties, which are further divided into townships and county-administered cities, each having elected mayors and city councilors who share duties with the county. Some divisions are indigenous divisions which have different degrees of autonomy to standard ones. In addition, districts, cities and townships are further divided into villages and neighborhoods. The provinces have been "streamlined" and are no longer functional.[423] Similarly, Mongol banners for China's Inner Mongolia also existed,[292] but they were abolished in 2006 and the ROC reaffirmed its recognition of Mongolia (formerly known as Outer Mongolia in Taiwan) in 2002, as stipulated in the 1946 constitution.[424][425][426]

With provinces non-functional, Taiwan is in practice divided into 22 subnational divisions, each with a self-governing body led by an elected leader and a legislative body with elected members. Duties of local governments include social services, education, urban planning, public construction, water management, environmental protection, transport, public safety, and more.

When the ROC retreated to Taiwan in 1949, its claimed territory consisted of 35 provinces, 12 special municipalities, 1 special administrative region and 2 autonomous regions. However, since its retreat, the ROC has controlled only Taiwan Province and some islands of Fujian Province. The ROC also controls the Pratas Islands and Taiping Island in the Spratly Islands, which are part of the disputed South China Sea Islands. They were placed under Kaohsiung administration after the retreat to Taiwan.[427]

- Notes

- ^ a b c d e f Has an elected executive and an elected legislative council.

- ^ a b c Has an appointed district administrator for managing local affairs and carrying out tasks commissioned by superior agency.

- ^ Has an elected village administrator for managing local affairs and carrying out tasks commissioned by superior agency.

Economy

The quick industrialization and rapid growth of Taiwan during the latter half of the 20th century has been called the "Taiwan Miracle". Taiwan is one of the "Four Asian Tigers" alongside Hong Kong, South Korea and Singapore. As of October 2022, Taiwan is the 21st largest economy in the world by nominal GDP.[428]

Since 2001, agriculture constituted less than 2 percent of GDP, down from 32 percent in 1951.[429] Unlike its neighbors, South Korea and Japan, the Taiwanese economy is dominated by small and medium-sized enterprises, rather than the large business groups.[430] Traditional labor-intensive industries are steadily being moved offshore and with more capital and technology-intensive industries replacing them. High-technology science parks have sprung up in Taiwan.

Today Taiwan has a dynamic, capitalist, export-driven economy with gradually decreasing state involvement in investment and foreign trade. In keeping with this trend, some large government-owned banks and industrial firms are being privatized.[431] Exports have provided the primary impetus for industrialization. The trade surplus is substantial, and Taiwan remained one of the world's largest forex reserve holders.[432] Taiwan's total trade in 2022 reached US$907 billion. Both exports and imports for the year reached record levels, totaling US$479.52 billion and US$427.60 billion, respectively.[433] China, United States and Japan are Taiwan's three largest trading partners, accounting for over 40 percent of total trade.[434]

Since the beginning of the 1990s, economic ties between Taiwan and China have been extensive. In 2002, China surpassed the United States to become Taiwan's largest export market for the first time.[435] China is also the most important target of outward foreign direct investment.[436] From 1991 to 2022, more than US$200 billion have been invested in China by Taiwanese companies.[437] China hosts around 4,200 Taiwanese enterprises and over 240,000 Taiwanese work in China.[438][439] Although the economy of Taiwan benefits from this situation, some have expressed the view that the island has become increasingly dependent on the mainland Chinese economy.[440] Others argue that close economic ties between Taiwan and mainland China would make any military intervention by the PLA against Taiwan very costly, and therefore less probable.[441]

Since the 1980s, a number of Taiwan-based technology firms have expanded their reach around the world.[442] Taiwan is a key player in the supply chain for advanced chips. Taiwan's rise in the key semiconductor industry was largely attributed to Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. (TSMC) and United Microelectronic Corporation (UMC).[443] TSMC was founded 21 February 1987 and as of December 2021 its market capitalization equated to roughly 90% of Taiwan's GDP.[444] The company is the 9th largest in the world by market capitalization[445] as well as the world's biggest semiconductor manufacturing company, surpassing Intel and Samsung.[446] UMC, another major company in Taiwan's high-tech exports and global semiconductors, competes with the American GlobalFoundries, and others, for less advanced semiconductor processes and for silicon wafers.[447] Other well-known international technology companies headquartered in Taiwan include personal computer manufacturers Acer Inc. and Asus, as well as electronics manufacturing giant Foxconn.[448]

Transport

The Ministry of Transportation and Communications of Taiwan is the cabinet-level governing body of the transport network in Taiwan. Civilian transport in Taiwan is characterized by extensive use of scooters. In March 2019, 13.86 million were registered, twice that of cars.[449] Both highways and railways are concentrated near the coasts, where the majority of the population resides, with 1,619 km (1,006 mi) of motorway. Railways in Taiwan are primarily used for passenger services, with Taiwan Railways Administration (TRA) operating a circular route around the island and Taiwan High Speed Rail (THSR) running high speed services on the west coast. Urban transit systems include Taipei Metro, Kaohsiung Metro, Taoyuan Metro, New Taipei Metro, and Taichung Metro.

Major airports include Taiwan Taoyuan, Kaohsiung, Taipei Songshan and Taichung. There are currently seven Taiwanese passenger airlines, with the largest two being China Airlines and EVA Air. There are seven international seaports: Keelung, Taipei, Suao, Taichung, Kaohsiung, Anping, and Hualien.[450] The Port of Kaohsiung handled the largest volume of cargo in Taiwan, with about 440 million shipping tonnes, which accounted for 58.6% of Taiwan's total throughput in 2021.[451] The shipping tonnage followed by Taichung (18.6%), Taipei (12%) and Keelung (8.7%).

Demographics

Taiwan has a population of about 23.4 million,[452] most of whom are on the island of Taiwan. The remainder live on the outlying islands of Penghu (101,758), Kinmen (127,723), and Matsu (12,506).[453]

Largest cities and counties

The figures below are the March 2019 estimates for the twenty most populous administrative divisions; a different ranking exists when considering the total metropolitan area populations (in such rankings the Taipei-Keelung metro area is by far the largest agglomeration). The figures reflect the number of household registrations in each city, which may differ from the number of actual residents.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ethnic groups

The ROC government reports that 95 percent of the population is ethnically Han Chinese.[454] There are also 2.4 percent indigenous Austronesian peoples and 2.6 percent new immigrants primarily from China and Southeast Asia.[455]

Most Han Taiwanese are descended from the Hoklo people, native to the coastal regions of southern Fujian, and the Hakka people, native to eastern Guangdong. Hoklo and Hakka migrants arrived in large numbers during the 17th and 18th century. Descendants of Hoklo now compose approximately 70 percent of Taiwan's population.[14] Descendants of Hakka make up about 15 percent of the population. Another minority group, called waishengren, comprises those who arrived from China during the 1940s or are descended from them.[456] Genetic studies indicate that the Hoklo and Hakka people are a mixture between Austronesians and Han people.[457]

Taiwanese Indigenous peoples number about 584,000, and the government recognises 16 groups.[458] The Ami, Atayal, Bunun, Kanakanavu, Kavalan, Paiwan, Puyuma, Rukai, Saisiyat, Saaroa, Sakizaya, Sediq, Thao, Truku and Tsou live mostly in the eastern half of the island, while the Yami inhabit Orchid Island.[459][460]

Languages

The Republic of China does not have any legally designated official language. Mandarin is the primary language used in business and education, and is spoken by the vast majority of the population. Traditional Chinese is used as the writing system.[461]

Around 70% of Taiwan's population belong to the Hoklo ethnic group and are native speakers of Taiwanese Hokkien.[462] The Hakka group, comprising some 14–18 percent of the population, speak Hakka. Although Mandarin is the language of instruction in schools and dominates television and radio, non-Mandarin Chinese varieties have undergone a revival in public life in Taiwan, particularly since restrictions on their use were lifted in the 1990s.[461]

Formosan languages are spoken primarily by the indigenous peoples of Taiwan. They do not belong to the Chinese or Sino-Tibetan language family, but to the Austronesian language family, and are written in the Latin alphabet.[463] Their use among aboriginal minority groups has been in decline as usage of Mandarin has risen.[461] Of the 14 extant languages, five are considered moribund.[464]

Since the May Fourth Movement, written vernacular Chinese had replaced Classical Chinese and emerged as the mainstream written Chinese in the Republic of China. Classical Chinese continued to be widely used in government documents until reforms in the 1970s to shift the written style to a more integrated vernacular Chinese and Classical Chinese style (文白合一行文).[465][466] On 1 January 2005, the Executive Yuan also changed its long-standing convention on the direction of writing in official documents from vertical to horizontal. Standalone Classical Chinese is occasionally used in formal or ceremonial occasions, such as religious or cultural rites. The National Anthem of the Republic of China (中華民國國歌), for example, is in Classical Chinese. Most official government, legal, and judiciary documents, as well as courts rulings use a combined vernacular Chinese and Classical Chinese style.[467] As many legal documents are still written in Classical Chinese, which is not easily understood by the general public, a group of Taiwanese have launched the Legal Vernacular Movement, hoping to bring more vernacular Chinese into the legal writings of the Republic of China.[468]

Taiwan is officially multilingual. A national language in Taiwan is legally defined as "a natural language used by an original people group of Taiwan and the Taiwan Sign Language".[9]

Religion

The Constitution of the Republic of China protects people's freedom of religion and the practices of belief.[469][470] The government respects freedom of religion, and Taiwan scores highly on the International IDEA's Global State of Democracy Indices for religious freedom.[471]

In 2005, the census reported that the five largest religions were: Buddhism, Taoism, Yiguandao, Protestantism, and Roman Catholicism.[472] According to Pew Research, the religious composition of Taiwan in 2020[473] is estimated to be 43.8 percent Folk religions, 21.2 percent Buddhist, 15.5 Others (including Taoism), 13.7 percent Unaffiliated, 5.8 percent Christian and 1% Muslim. Taiwanese aborigines comprise a notable subgroup among professing Christians.[474] There has been a small Muslim community of Hui people in Taiwan since the 17th century.[475]

Confucianism serves as the foundation of both Chinese and Taiwanese culture. The majority of Taiwanese people usually combine the secular moral teachings of Confucianism with whatever religions they are affiliated with.

As of 2019[update], there were 15,175 religious buildings in Taiwan, approximately one place of worship per 1,572 residents. 12,279 temples were dedicated to Taoism and Buddhism. There were 9,684 Taoist Temples and 2,317 Buddhist Temples.[476] For Christianity, there are 2,845 Churches.[476] On average, there is one temple or church (church) or religious building for every square kilometer. The density of religions and religious buildings in Taiwan is among the highest in the world.[477][478]

A significant percentage of the population is non-religious. Taiwan's lack of state-sanctioned discrimination, and generally high regard for freedom of religion or belief earned it a joint #1 ranking in the 2018 Freedom of Thought Report.[479][480] On the other hand, the Indonesian migrant worker community in Taiwan (estimated to total 258,084 people) has experienced religious restrictions by local employers or the government.[481][482]

Education