Maria Theresa Reef

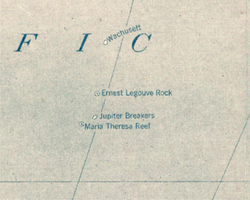

Maria Theresa Reef on 1921 Pacific map | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Pacific Ocean |

| Coordinates | 36°50′S 136°39′W / 36.833°S 136.650°W |

| Type | Phantom island |

The Maria Theresa Reef is a supposed reef in the South Pacific (south of the French Tuamotu islands and east of New Zealand); it appears to be a phantom reef. It is also known as Tabor Island or Tabor Reef on French maps.

Reports

[edit]Bernhard Krauth explains that Tabor/Maria Theresa's existence was reported in three contemporary newspapers as a dangerous reef seen on 16 November 1843 by a Captain Asaph P. Taber (not "Tabor") of the Maria-Theresa, a New Bedford, Massachusetts, whaler, to be situated at 37°00′S 151°00′W / 37.000°S 151.000°W, later adjusted to 37°00′S 151°13′W / 37.000°S 151.217°W.[1][2]

According to Krauth, who makes, however, several mistakes, the logbook of the Maria Theresa may read "Saw breakers." This means that the Captain recorded simply that he saw "breakers," which are sections of reef against which waves break, thus signaling that an island or system of reefs is near. Krauth further claims that Tabor would be in French waters if it existed.[2]

Jean-Paul Faivre reports that map no. 5356 of the (French) Naval Hydrographic Office and the folding map in "Malte-Brun revised by E. Cortambert, vol. 4" (without further reference) both mark "Maria-Theresa," apparently 153 degrees W of Greenwich, and that no. 5356 also marks Ernest Legouve Reef.[3]

Hugh Cassidy, discussing his escapades, claims that "A nautical chart... issued by the W. Faden Company, Oceanographers to the King [George III], in 1817 lists Maria Theresa." The shoal also apparently appears in US Hydrographic Office chart no. 2683 (1978), together with others in the vicinity.[4]

Tabor was unsuccessfully searched for in 1957. New Zealand's HMNZS Tui made an extensive search of the area in the 1970s and found no shallows or islands. The depths in the region were shown to be 2,734 fathoms (5,000 m). In 1983, the position of the reef was recalculated at 36°50′S 136°39′W / 36.833°S 136.650°W, more than 1,000 km further east, and searched for, but not found. Its existence is doubtful.

In 1966 amateur radio journal "CQ" published a photo and description of Don Miller transmitting from what he claimed was Maria Teresa Reef.[5] This has been since proven to be a hoax.

Other nearby historically reported reefs which also may not exist are: Jupiter Reef, Wachusett Reef, and Ernest Legouve Reef (the supposed site of the fictional "Lincoln Island" of Jules Verne's The Mysterious Island). The historical sightings of these reefs were probably inspired by the supposed existence of Maria Theresa Reef. Even in the 21st century, some map and atlas publishers still show this fictitious group of reefs in the South Pacific.

In fiction

[edit]The island appears in Jules Verne's novels In Search of the Castaways and The Mysterious Island.[2] It is also present in Verne's play, Captain Grant's Children, but under a different name. Tabor is replaced by the imaginary "Balker Isle of the southern seas, situated not far from Adelie Coast" : like Tabor, at 37 degrees South, but with the longitude moved to 165 degrees West.[6][7]

In In Search of the Castaways (The Children of Captain Grant), the island shelters Captain Grant and two of his crew. Its coordinates being half-erased in the help message found by the children, it takes them months to find the castaways, with the help of Lord Glenarvan on board of his yacht "Duncan". Its coordinates are eventually given as 37°11′S 153°00′W / 37.183°S 153.000°W using the Paris meridian. At the end of the book, Ayrton, the renegade, is left in Grant's place to live among the beasts and regain his humanity.

In The Mysterious Island, after they have settled on Lincoln Island, the heroes travel to Tabor island using a small ship, meet Ayrton, and bring him back to civilisation and rehabilitation. The same coordinates for Tabor Island are given here as in Castaways, except this time using the Greenwich meridian.

The island is described, in the Sidney Kravitz translation, as having a low coast "barely emerging from the waves" ; as being "much smaller than Lincoln Island" ; having a "twisting channel of reefs" ; and being unmistakable since "according to the most recent maps, no other island existed in this portion of the Pacific between New Zealand and the American coast."[8] If Verne is referring to real maps or current sightings, these would be as of 1873-1874.

Verne goes on to explain that "It was really an islet, measuring no more than six miles in circumference, an elongated oval hardly fringed by any capes or promontories, coves, or creeks."[9]

Returning to the story, after Lincoln Island is destroyed by explosion of its volcano, they are saved by "Duncan" whose crew was looking for Ayrton on Tabor island, but instead found there a note, indicating the existence of Lincoln island sheltering the heroes and Ayrton. The note turns out to have been specifically left on Tabor island by the benevolent Captain Nemo.

The Vernian scholar, William Butcher, to sum up a complex situation of locating Tabor Island in real life, explains that Verne positions Tabor 153 degrees W of both Paris (as in Castaways) and Greenwich (as in Mysterious Island), whereas in real life it would be about 151 or 153 degrees W of only Greenwich (according to Krauth and Faivre, respectively). Furthermore, the character Cyrus Smith of The Mysterious Island seems to go wrong in his calculation of Tabor's position, possibly by as much as four degrees. Since Lincoln Island is positioned with reference to Tabor, this in turn means that the position of the Island can not reliably be determined. They could in fact be one and the same island due to a misreading of a meridian.[4]

References

[edit]- ^ Great Britain Hydrographic Dept (1900). Pacific Islands, v. 3 (3 ed.). London: J. D. Potter. p. 27. Retrieved 2011-09-26.

- ^ a b c Krauth, Bernhard (1987). "Le Récif Maria-Theresa". Bulletin de la société Jules Verne. 84 (32): 22.

- ^ "Jules Verne (1828-1905) et le Pacifique". Journal de la société des océanistes. 11: 135–147. 1965.

- ^ a b William Butcher (2001). "Introduction". In Jules Verne (ed.). The Mysterious Island. Translated by Sidney Kravitz. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press. p. xxiv.

- ^ "Don Miller, W9WNV, DXpeditioner". CQ; the Radio Amateur's Journal. 22 (7–12). Cowan: 69. 1966. Retrieved 2011-09-26.

- ^ William Butcher (2001). "Appendix B: Verne's Other Writing on the Desert-Island Theme". In Jules Verne (ed.). The Mysterious Island. Translated by Sidney Kravitz. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press. p. 675.

- ^ Information can be found in Pierre Terrasse, "Un Centenaire: Les Enfants du capitaine Grant au theater," BSJV 49 (1979): 21-31.

- ^ Verne, Jules (2001). Evans, Arthur B. (ed.). The Mysterious Island. Translated by Kravitz, Sidney. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press. pp. 350–351.

- ^ Verne, Jules (2001). Evans, Arthur B. (ed.). The Mysterious Island. Translated by Kravitz, Sidney. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press. p. 352.

Further reading and external links

[edit]- Eade, J. V. (1976). Geological notes on the Southwest Pacific Basin in the area of Wachusett Reef and Maria Theresa Reef. Wellington: New Zealand Oceanographic Institute.

- German article with map: Die Kinder des Kapitän Grant – Detail 4: Wo liegt Grant's Insel?