Calligraphy

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Calligraphy (from Ancient Greek καλλιγραφία (kalligraphía) 'beautiful writing') is a visual art related to writing. It is the design and execution of lettering with a pen, ink brush, or other writing instrument.[1]: 17 Contemporary calligraphic practice can be defined as "the art of giving form to signs in an expressive, harmonious, and skillful manner".[1]: 18

In East Asia and the Islamic world, where more flexibility is allowed in written forms, calligraphy is regarded as a significant art form, and the form it takes may be affected by the meaning of the text or the individual words.

In the Western world, the aim of calligraphy is normally regarded as only to achieve attractive writing that is usually consistent within each piece of writing,[by whom?] with little or no interpretation of the text attempted.[citation needed]

Modern Western calligraphy ranges from functional inscriptions and designs to fine-art pieces where the letters may or may not be readable.[1][page needed] Classical calligraphy differs from type design and non-classical hand-lettering, though a calligrapher may practice both.[2][3][4][5]

Western calligraphy continues to flourish in the forms of wedding invitations and event invitations, font design and typography, original hand-lettered logo design, religious art, announcements, graphic design and commissioned calligraphic art, cut stone inscriptions, and memorial documents. It is also used for props, moving images for film and television, testimonials, birth and death certificates, maps, and other written works.[6][7]

Tools

[edit]Pens and brushes

[edit]The principal tools for a calligrapher are the pen and the brush. The pens used in calligraphy can have nibs that may be flat, round, or pointed.[8][9][10] For decorative purposes, multi-nibbed pens (steel brushes) can be used. However, works have also been created with felt-tip and ballpoint pens, although these works do not employ angled lines. There are certain styles of calligraphy, such as Gothic script, that require a stub nib pen.

The examples and perspective in this section deal primarily with Western World and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (October 2024) |

Common calligraphy pens and brushes include:

Inks, papers, and templates

[edit]The ink used for writing is usually water-based and is much less viscous than the oil-based ink used in printing. Certain specialty paper with high ink absorption and constant texture enables cleaner lines,[11] although parchment or vellum is often used, as a knife can be used to erase imperfections and a light-box is not needed to allow lines to be visible through it. Normally, light boxes and templates are used to achieve straight lines without pencil markings detracting from the work. Ruled paper, either for a light box or direct use, is most often ruled every quarter or half an inch, although inch spaces are occasionally used. This is the case with litterea unciales (hence the name)[further explanation needed], and college-ruled paper often acts as a guideline well.[12]

| Part of a series on |

| Calligraphy |

|---|

|

East Asia

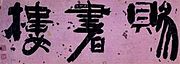

[edit]Chinese calligraphy is locally called shūfǎ or fǎshū (書法 or 法書 in traditional Chinese, literally "the method or law of writing"); Japanese calligraphy is shodō (書道, literally "the way or principle of writing");[13] and Korean calligraphy is called seoye (Korean: 서예; Hanja: 書藝; literally "the art of writing");[14] The calligraphy of East Asian characters continues to form an important and appreciated constituent of contemporary traditional East Asian culture.[examples needed][citation needed]

-

On Calligraphy by Mi Fu, Song dynasty (China)

-

Japanese calligraphy: Two Chinese characters "平和" meaning "peace" and the signature of Japanese calligrapher Ōura Kanetake (1910). Horizontal writing.

-

Calligraphy by one of Korea's most celebrated calligraphists, Kim Jeong-hui (1786–1856)

-

Modern Korean calligraphy in Hangul, meaning "Wiktionary"

History

[edit]In ancient China, the oldest known Chinese characters are oracle bone script (甲骨文), carved on ox scapulae and tortoise plastrons, as the rulers in the Shang dynasty carved pits on such animals' bones and then baked them to gain auspice of military affairs, agricultural harvest, or even procreation and weather. During the divination ceremony, after the cracks were made[further explanation needed], the characters were written with a brush on the shell or bone to be later carved.[15][full citation needed] With the development of the bronzeware script (jīn wén) and large seal script (dà zhuàn)[16] "cursive" signs continued[further explanation needed]. Mao Gong Ding is one of the most famous and typical bronzeware scripts in Chinese calligraphic history. It has 500 characters inscribed onto the bronze which is the largest number of bronze inscription we have discovered so far.[clarification needed][17] Moreover, each archaic kingdom of current China had its own set of characters.

In Imperial China, the graphs on old steles — some dating from 200 BCE, and in the small seal script (小篆 xiǎo zhuàn) style — have been preserved and can be viewed in museums even today.

About 220 BCE, the emperor Qin Shi Huang, the first to conquer the entire Chinese basin, imposed several reforms, among them Li Si's character unification, which created a set of 3300 standardized small seal characters.[18] Despite the fact that the main writing implement of the time was already the brush, few papers survive from this period, and the main examples of this style are on steles.

The clerical script (隸書/隸书) (lì shū) which was more regularized, and in some ways similar to modern text, was also authorised under Qin Shi Huang.[19]

Between clerical script and traditional regular script, there is another transitional type of calligraphic work called Wei Bei. It started during the North and South dynasties (420 to 589 CE) and ended before the Tang dynasty (618–907).[20]

The traditional regular script (kǎi shū), still in use today, and largely finalized by Zhong You (鐘繇, 151–230) and his followers, is even more regularized. Its spread was encouraged by Emperor Mingzong of Later Tang (926–933), who ordered the printing of the classics using new wooden blocks in kaishu[further explanation needed]. Printing technologies here allowed a shape stabilization. The kaishu shape of characters 1000 years ago was mostly similar to that at the end of Imperial China;[citation needed] However, small changes to the characters have been made. For example the shape of 广 has changed from the version in the Kangxi Dictionary of 1716 to the version found in modern books. The Kangxi and current shapes have tiny differences, while stroke order remains the same, according to the old style.[21]

Styles which did not survive include bāfēnshū, a mix of 80% small seal script and 20% clerical script[clarification needed]. Some variant Chinese characters were unorthodox or locally used for centuries. They were generally understood but always rejected in official texts. Some of these unorthodox variants, in addition to some newly created characters, compose the simplified Chinese character set.[citation needed]

Technique

[edit]Traditional East Asian writing uses the Four Treasures of the Study[22] — ink brushes known as máobǐ (毛筆/毛笔), Chinese ink, paper, and inkstones — to write Chinese characters. These instruments of writing are also known as the Four Friends of the Study (Korean: 문방사우/文房四友, romanized: Munbang sau) in Korea. Besides the traditional four tools, desk pads and paperweights are also used.

Many different parameters influence the final result of a calligrapher's work. Physical parameters include the shape, size, stretch, and hair type of the ink brush; the color, color density and water density of the ink; as well as the paper's water absorption speed and surface texture. The calligrapher's technique also influences the result, as the look of finished characters are influenced by the quantity of ink and water the calligrapher lets the brush absorb and by the pressure, inclination, and direction of the brush. Changing these variables produces thinner or bolder strokes, and smooth or toothed borders. Eventually, the speed, accelerations and decelerations of a skilled calligrapher's movements aim to give "spirit" to the characters, greatly influencing their final shapes.

Styles

[edit]Cursive styles such as xíngshū (行書/行书)(semi-cursive or running script) and cǎoshū (草書/草书)(cursive, rough script, or grass script) are less constrained and faster, where movements made by the writing implement are more visible. These styles' stroke orders vary more, sometimes creating radically different forms. They are descended from the clerical script, in the same time as the regular script (Han dynasty), but xíngshū and cǎoshū were used for personal notes only, and never used as a standard. The cǎoshū style was highly appreciated during Emperor Wu of Han's reign (140–187 CE).[citation needed]

Examples of modern printed styles are Song from the Song dynasty's printing press, and sans-serif. These are not considered traditional styles, and are normally not written.

Influences

[edit]Japanese and Korean calligraphy were each greatly influenced by Chinese calligraphy. Calligraphy has influenced most major art styles in East Asia, including ink and wash painting, a style of Chinese, Japanese, and Korean painting based entirely on calligraphy and which uses similar tools and techniques.

The Japanese and Koreans have also developed their own specific sensibilities and styles of calligraphy while incorporating Chinese influences.

Japan

[edit]Japanese calligraphy goes out of the set of CJK strokes to also include local alphabets such as hiragana and katakana, with specific problematics such as new curves and moves, and specific materials (Japanese paper, washi 和紙, and Japanese ink).[23]

Korea

[edit]The modern Korean alphabet and its use of the circle required the creation of a new technique not used in traditional Chinese calligraphy.

Mongolia

[edit]Mongolian calligraphy is also influenced by Chinese calligraphy, from tools to style.[citation needed][further explanation needed]

Tibet

[edit]Tibetan calligraphy is central to Tibetan culture. The script is derived from Indic scripts. The nobles of Tibet, such as the High Lamas and inhabitants of the Potala Palace, were often capable calligraphers. Tibet has been a center of Buddhism for several centuries, with said religion placing a high significance on the written word. This does not provide for a large body of secular pieces, although they do exist (but are usually related in some way to Tibetan Buddhism). Almost all high religious writing involved calligraphy, including letters sent by the Dalai Lama and other religious and secular authorities. Calligraphy is particularly evident on their prayer wheels, although this calligraphy was forged rather than scribed, much like Arab and Roman calligraphy is often found on buildings. Although originally done with a reed, Tibetan calligraphers now use chisel tipped pens and markers as well.[citation needed]

Southeast Asia

[edit]Philippines

[edit]The Philippines has numerous ancient and indigenous scripts collectively called as Suyat scripts. Various ethno-linguistic groups in the Philippines prior to Spanish colonization in the 16th century up to the independence era in the 21st century have used the scripts with various mediums. By the end of colonialism, only four of the suyat scripts had survived and continued to be used by certain communities in everyday life. These four scripts are Hanunó'o/Hanunoo of the Hanuno'o Mangyan people, Buhid/Build of the Buhid Mangyan people, Tagbanwa script of the Tagbanwa people, and Palaw'an/Pala'wan of the Palaw'an people. All four scripts were inscribed in the UNESCO Memory of the World Programme, under the name Philippine Paleographs (Hanunoo, Build, Tagbanua and Pala’wan), in 1999.[24]

Due to dissent from colonialism, many artists and cultural experts have revived the usage of suyat scripts that went extinct due their replacement by the Spanish-introduced Latin alphabet. These scripts being revived include the Kulitan script of the Kapampangan people, the badlit script of various Visayan ethnic groups, the Iniskaya script of the Eskaya people, the Baybayin script of the Tagalog people, and the Kur-itan script of the Ilocano people, among many others.[25][26][27] Due to the diversity of suyat scripts, all calligraphy written in suyat scripts are collectively called as Filipino suyat calligraphy, although each are distinct from each other.[28][29] Calligraphy using the Western alphabet and the Arabic alphabet are also prevalent in the Philippines due to its colonial past, but the Western alphabet and the Arabic alphabet are not considered as suyat, and therefore Western-alphabet and Arabic calligraphy are not considered as suyat calligraphy.[30][31]

Vietnam

[edit]Vietnamese calligraphy is called thư pháp (書法, literally "the way of letters or words") and is based on Chữ Nôm and Chữ Hán, the historical Vietnamese writing system rooted in the impact of Chinese characters and replaced with the Latin alphabet as a result of French colonial influence. However, the calligraphic traditions maintaining the historical employment of Han characters continue to be preserved in modern Vietnamese calligraphy.[32]

South Asia

[edit]

Religious texts preservation is the most common purpose for Indian calligraphy. Monastic Buddhist communities had members trained in calligraphy and shared responsibility for duplicating sacred scriptures.[33] Jaina traders incorporated illustrated manuscripts celebrating Jaina saints. These manuscripts were produced using inexpensive material, like palm leave and birch, with fine calligraphy.[34]

Nepal

[edit]Nepalese calligraphy is primarily created using the Ranjana script. The script itself, along with its derivatives (like Lantsa, Phagpa, Kutila) are used in Nepal, Tibet, Bhutan, Leh, Mongolia, coastal Japan, and Korea to write "Om mani padme hum" and other sacred Buddhist texts, mainly those derived from Sanskrit and Pali.[citation needed]

Africa

[edit]Egypt

[edit]Egyptian hieroglyphs were the formal writing system used in Ancient Egypt. Hieroglyphs combined logographic, syllabic and alphabetic elements, with a total of some 1,000 distinct characters.

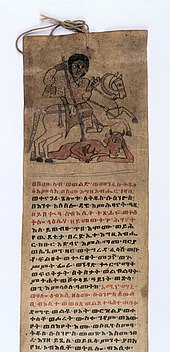

Ethiopia

[edit]

Ethiopian (Abyssinian) calligraphy began with the Ge'ez script, which replaced Epigraphic South Arabian in the Kingdom of Aksum, which was developed specifically for Ethiopian Semitic languages. In those languages that use it, such as Amharic and Tigrinya, the script is called Fidäl, which means script or alphabet. The Epigraphic South Arabian letters were used for a few inscriptions into the 8th century, though not in any South Arabian language since Dʿmt.

Early inscriptions in Ge'ez and Ge'ez script are dated to as early as the 5th century BCE, with a sort of proto-Ge'ez written in ESA since the 9th century BCE. Ge'ez literature begins with the Christianization of Ethiopia (and the civilization of Axum) in the 4th century, during the reign of Ezana of Axum.

The Ge'ez script is read from left to right and has been adapted to write other languages, usually ones that are also Semitic. The most widespread use is for Amharic in Ethiopia and Tigrinya in Eritrea and Ethiopia.[citation needed]

Americas

[edit]Maya

[edit]Maya calligraphy was expressed via Maya glyphs; modern Maya calligraphy is mainly used on seals and monuments in the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico. Maya glyphs are rarely used in government offices; however, in Campeche, Yucatán and Quintana Roo, calligraphy in Maya languages is written in Latin script rather than Maya glyphs. Some commercial companies in southern Mexico use Maya glyphs as symbols of their business. Some community associations and modern Maya brotherhoods use Maya glyphs as symbols of their groups.[citation needed]

Most of the archaeological sites in Mexico such as Chichen Itza, Labna, Uxmal, Edzna, Calakmul, etc. have glyphs in their structures. Carved stone monuments known as stele are common sources of ancient Maya calligraphy.[citation needed]

Europe

[edit]-

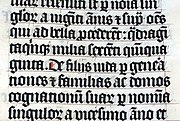

Calligraphy in a Latin Bible of 1407 on display in Malmesbury Abbey, England. This Bible was hand-written in Belgium, by Gerard Brils, for reading aloud in a monastery.

-

Georgian calligraphy is a centuries-old tradition of an artistic writing of the Georgian language with its three scripts.

-

Modern Western calligraphy

Calligraphy in Europe is recognizable in the use of the Latin script in Western Europe, and in the use of the Greek, Armenian, and Georgian, and Cyrillic scripts in Eastern Europe.

Ancient Rome

[edit]The Latin alphabet appeared about 600 BCE in ancient Rome, and by the first century CE it had developed into Roman imperial capitals carved on stones, rustic capitals painted on walls, and Roman cursive for daily use. In the second and third centuries the uncial lettering style developed. As writing withdrew to monasteries, uncial script was found more suitable for copying the Bible and other religious texts. It was the monasteries which preserved calligraphic traditions during the fourth and fifth centuries, when the Roman Empire fell and Europe entered the early Middle Ages.[35]

At the height of the Roman Empire, its power reached as far as Great Britain; when the empire fell, its literary influence remained. The Semi-uncial generated the Irish Semi-uncial, the small Anglo-Saxon.[36] Each region developed its own standards following the main monastery of the region (i.e. Merovingian script, Laon script, Luxeuil script, Visigothic script, Beneventan script), which are mostly cursive and hardly readable[opinion][clarification needed].

Western Christendom

[edit]Christian churches promoted the development of writing through the prolific copying of the Bible, the Breviary, and other sacred texts.[37] Two distinct styles of writing known as uncial and half-uncial (from the Latin uncia, or "inch") developed from a variety of Roman bookhands.[38] The 7th–9th centuries in northern Europe were the heyday of Celtic illuminated manuscripts, such as the Book of Durrow, Lindisfarne Gospels and the Book of Kells.[39]

Charlemagne's devotion to improved scholarship resulted in the recruiting of "a crowd of scribes", according to Alcuin, the Abbot of York.[40] Alcuin developed the style known as the Caroline or Carolingian minuscule. The first manuscript in this hand was the Godescalc Evangelistary (finished 783) — a Gospel book written by the scribe Godescalc.[41] Carolingian remains the one progenitor hand from which modern booktype descends.[42]

In the eleventh century, the Caroline evolved into the blackletter ("Gothic") script, which was more compact and made it possible to fit more text on a page.[43]: 72 The Gothic calligraphy styles became dominant throughout Europe and, in 1454, when Johannes Gutenberg developed the first printing press in Mainz, Germany, the Gothic style was adopted for its use, making it the first typeface.[43]: 141

In the 15th century, the rediscovery of old Carolingian texts encouraged the creation of the humanist minuscule or littera antiqua. The 17th century saw the Batarde script from France, and the 18th century saw the English script spread across Europe and world through their books.

In the mid-1600s French officials, flooded with documents written in various hands and varied levels of skill, complained that many such documents were beyond their ability to decipher. The Office of the Financier thereupon restricted all legal documents to three hands, namely the Coulee, the Rhonde, (known as Round hand in English) and a Speed Hand sometimes called the Bastarda.[44]

While there were many great French masters at the time, the most influential in proposing these hands was Louis Barbedor, who published Les Ecritures Financière Et Italienne Bastarde Dans Leur Naturel c. 1650.[44]

With the destruction of the Camera Apostolica during the sack of Rome (1527), the capitol for writing masters moved to Southern France. By 1600, the Italic Cursiva began to be replaced by a technological refinement, the Italic Chancery Circumflessa, which in turn fathered the Rhonde and later English Roundhand.[44]

In England, Ayres and Banson popularized the Round Hand while Snell is noted for his reaction to them, and warnings of restraint and proportionality. Still Edward Crocker began publishing his copybooks 40 years before the aforementioned.[44][clarification needed]

Eastern Europe

[edit]Other European styles use the same tools and practices, but differ by character set and stylistic preferences. For Slavonic lettering, the history of the Slavonic and consequently Russian writing systems differs fundamentally from the one of the Latin language, having evolved from the 10th century to today.

Style

[edit]Unlike a typeface, handwritten calligraphy is characterised by irregularity in the characters which vary in size, shape, style, and color, producing a distinct aesthetic value, although it may also make the content more difficult to decode for some readers. As with Chinese or Islamic calligraphy, Western calligraphic script employed the use of strict rules and shapes. Quality writing had a rhythm and regularity to the letters, with a "geometrical" order of the lines on the page. Each character had, and often still has, a precise stroke order.

Sacred Western calligraphy has some unique features, such as the illumination of the first letter of each book or chapter in medieval times. A decorative "carpet page" may precede the literature, filled with ornate, geometrical depictions of bold-hued animals. The Lindisfarne Gospels (715–720 CE) are an early example.[45] Many of the themes and variations of today's contemporary Western calligraphy are found in the pages of The Saint John's Bible. A particularly modern example is Timothy Botts' illustrated edition of the Bible, with 360 calligraphic images as well as a calligraphy typeface.[46]

Islamic world

[edit]-

Bowl with Kufic Calligraphy, (Persia) 10th century

-

Sample showing Nastaliq proportional rules (Persian and Urdu languages)[citation needed]

Islamic calligraphy[a] has evolved alongside Islam and the Arabic language. As it is based on Arabic letters, some call it "Arabic calligraphy". However the term "Islamic calligraphy" is a more appropriate term as it comprises all works of calligraphy by Muslim calligraphers of different national cultures, such as Persian or Ottoman calligraphy, from Al-Andalus in medieval Spain to China.

Islamic calligraphy is associated with geometric Islamic art (Arabesque) on the walls and ceilings of mosques as well as on the page or other materials. Contemporary artists in the Islamic world may draw on the heritage of calligraphy to create modern calligraphic inscriptions, like corporate logos, or abstractions.

Instead of recalling something related to the spoken word, calligraphy for Muslims is a visible expression of the highest art of all, the art of the spiritual world. Calligraphy has arguably become the most venerated form of Islamic art because it provides a link between the languages of the Muslims with the religion of Islam. The Qur'an has played an important role in the development and evolution of the Arabic language, and by extension, calligraphy in the Arabic alphabet. Proverbs and passages from the Qur'an continue to be sources for Islamic calligraphy.

During the Ottoman civilization, Islamic calligraphy attained special prominence. The city of Istanbul is an open exhibition hall for all kinds and varieties of calligraphy, from inscriptions in mosques to fountains, schools, houses, etc.[47]

Antiquity

[edit]It is believed[by whom?] that ancient Persian script was invented by about 600–500 BCE to provide monument inscriptions for the Achaemenid kings.[citation needed] These scripts consisted of horizontal, vertical, and diagonal nail-shape letters, which is why it is called cuneiform script (lit. "script of nails") (khat-e-mikhi) in Persian.[relevant?] Centuries later, other scripts such as "Pahlavi" and "Avestan" scripts were used in ancient Persia. Pahlavi was a middle Persian script developed from the Aramaic script and became the official script of the Sassanian empire (224–651 CE).[citation needed]

Contemporary scripts

[edit]The Nasta'liq style is the most popular contemporary style among classical Persian calligraphy scripts;[citation needed] Persian calligraphers call it the "bride of calligraphy scripts." This calligraphy style has been based on such a rigid structure that it has changed very little since Mir Ali Tabrizi had found the optimum composition of the letters and graphical rules.[citation needed][opinion] It has just been fine-tuned during the past seven centuries.[clarification needed] It has very strict rules for graphical shape of the letters and for combination of the letters, words, and composition of the whole calligraphy piece.[citation needed]

Modern calligraphy

[edit]Revival

[edit]After printing became ubiquitous from the 15th century onward, the production of illuminated manuscripts began to decline.[37][48][full citation needed] However, the rise of printing did not mean the end of calligraphy.[37][4][49] A clear distinction between handwriting and more elaborate forms of lettering and script began to make its way into manuscripts and books at the beginning of the 16th century.

The modern revival of calligraphy began at the end of the 19th century, influenced by the aesthetics and philosophy of William Morris and the Arts and Crafts movement. Edward Johnston is regarded as being the father of modern calligraphy.[50][51][52] After studying published copies of manuscripts by architect William Harrison Cowlishaw, he was introduced to William Lethaby in 1898, principal of the Central School of Arts and Crafts, who advised him to study manuscripts at the British Museum.[b]

This triggered Johnston's interest in the art of calligraphy with the use of a broad-edged pen. He began a teaching course in calligraphy at the Central School in Southampton Row, London from September 1899, where he influenced the typeface designer and sculptor Eric Gill. He was commissioned by Frank Pick to design a new typeface for London Underground, still used today (with minor modifications).[53]

He has been credited for single-handedly reviving the art of modern penmanship and lettering through his books and teachings[by whom?] — his handbook on the subject, Writing & Illuminating, & Lettering (1906) was particularly influential on a generation of British typographers and calligraphers, including Graily Hewitt, Stanley Morison, Eric Gill, Alfred Fairbank and Anna Simons. Johnston also devised the crafted round calligraphic handwriting style, written with a broad pen, known today as the Foundational hand. Johnston initially taught his students an uncial hand using a flat pen angle, but later taught his hand using a slanted pen angle.[54] He first referred to this hand as "Foundational Hand" in his 1909 publication, Manuscript & Inscription Letters for Schools and Classes and for the Use of Craftsmen.[55]

Subsequent developments

[edit]Graily Hewitt taught at the Central School of Arts and Crafts and published together with Johnston throughout the early part of the century. Hewitt was central[citation needed] to the revival of gilding in calligraphy, and his prolific output on type design also appeared between 1915 and 1943. He is attributed with the revival of gilding with gesso and gold leaf on vellum. Hewitt helped found the Society of Scribes & Illuminators (SSI) in 1921, probably the world's foremost calligraphy society.[citation needed]

This article contains wording that promotes the subject in a subjective manner without imparting real information. (October 2024) |

Hewitt is not without both critics[56][full citation needed] and supporters[57] in his rendering of Cennino Cennini's medieval gesso recipes.[58] Donald Jackson, a British calligrapher, has sourced his gesso recipes from earlier centuries, a number of which are not presently in English translation.[59] Graily Hewitt created the patent announcing the award to Prince Philip of the title of Duke of Edinburgh on November 19, 1947, the day before his marriage to Queen Elizabeth.[60][clarification needed]

Anna Simons, Johnston's pupil, was instrumental in sparking interest in calligraphy in Germany with her German translation of Writing and Illuminating, and Lettering in 1910.[50] Austrian Rudolf Larisch, a teacher of lettering at the Vienna School of Art, published six lettering books that greatly influenced German-speaking calligraphers. Because German-speaking countries had not abandoned the Gothic hand in printing, Gothic also had a powerful effect on their styles.

Rudolf Koch was a friend and younger contemporary of Larisch. Koch's books, type designs, and teaching made him one of the most influential calligraphers of the 20th century in northern Europe and later in the U.S. Larisch and Koch taught and inspired many European calligraphers, notably Karlgeorg Hoefer and Hermann Zapf.[61]

Contemporary typefaces used by computers, from word processors like Microsoft Word or Apple Pages to professional design software packages like Adobe InDesign, find their roots in the both calligraphy of the past as well as several professional typeface designers.[1][4][62]

-

Banknote motif: number 5 against a circular panel of lace-like lathe work with a scalloped edge

-

Chinese soldier in calligraphy competition

-

Edward Johnston, a famous British calligrapher, at work in 1902

See also

[edit]- Handwriting script – style of handwritten document

- Asemic writing – Wordless open semantic form of writing

- Bastarda – Blackletter script used in France and Germany

- Blackletter – Historic European script and typeface

- Book hand – Legible handwriting style

- Brāhmī script – Ancient script of Central and South Asia

- Calligraffiti – Calligraphy/typography/graffiti art form

- Chancery hand – Any of several styles of historic handwriting

- Concrete poetry – Genre of poetry with lines arranged as a shape

- Court hand – Style of handwriting used in medieval English law courts

- Cursive – Style of penmanship

- Handstyle – In graffiti culture, the unique handwriting of an artist

- Handwriting – Writing created by a person with a writing implement

- History of writing

- Italic script – Style of handwriting and calligraphy developed in Italy

- Lettering – The art of drawing letters

- List of calligraphers

- Mathematical Alphanumeric Symbols – Unicode block

- Micrography – Art genre using minute Hebrew letters

- Palaeography – Study of handwriting and manuscripts

- Penmanship – Technique of writing with the hand

- Ronde script (calligraphy)

- Rotunda (script) – Medieval blackletter script

- Round hand – Type of handwriting

- Secretary hand – Style of European handwriting

- Siyah mashq – Calligraphic practice sheets

- Sofer – Jewish scribe

- Tag (graffiti) – Form of graffiti

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Mediaville, Claude (1996). Calligraphy: From Calligraphy to Abstract Painting. Belgium: Scirpus-Publications. ISBN 978-90-803325-1-5.

- ^ Pott, G. (2006). Kalligrafie: Intensiv Training [Calligraphy: Intensive Training] (in German). Verlag Hermann Schmidt. ISBN 978-3-87439-700-1.

- ^ Pott, G. (2005). Kalligrafie: Erste Hilfe und Schrift-Training mit Muster-Alphabeten (in German). Verlag Hermann Schmidt. ISBN 978-3-87439-675-2.

- ^ a b c Zapf 2007.

- ^ Zapf, H. (2006). The World of Alphabets: A kaleidoscope of drawings and letterforms. CD-ROM

- ^ Propfe, J. (2005). SchreibKunstRaume: Kalligraphie im Raum Verlag (in German). Munich: Callwey Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7667-1630-9.

- ^ Geddes, A.; Dion, C. (2004). Miracle: a celebration of new life. Auckland: Photogenique Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7407-4696-3.

- ^ Reaves, M.; Schulte, E. (2006). Brush Lettering: An instructional manual in Western brush calligraphy (Revised ed.). New York: Design Books.

- ^ Child, H., ed. (1985). The Calligrapher's Handbook. Taplinger Publishing Co.

- ^ Lamb, C.M., ed. (1976) [1956]. Calligrapher's Handbook. Pentalic.

- ^ "Paper Properties in Arabic calligraphy". calligraphyfonts.info. Archived from the original on 13 March 2017. Retrieved 1 June 2007.

- ^ "Calligraphy Islamic website". Calligraphyislamic.com. Archived from the original on 8 June 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ Sato, Shozo (11 March 2014). Shodo: The Quiet Art of Japanese Zen Calligraphy, Learn the Wisdom of Zen Through Traditional Brush Painting. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4629-1188-2.

- ^ Nornes, Abé Markus (22 February 2021). Brushed in Light: Calligraphy in East Asian Cinema. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-13255-3.

- ^ Keightley, 1978.

- ^ "Categories of Calligraphy – Seal Script". Retrieved 30 May 2018.

- ^ "The Bell and Cauldron Inscriptions-A Feast of Chinese Characters: The Origin and Development_Mao Gong Ding". Archived from the original on 18 October 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2018.

- ^ Fazzioli, Edoardo (1987). Chinese Calligraphy: From Pictograph to Ideogram: The History Of 214 Essential Chinese/Japanese Characters. Calligraphy by Rebecca Hon Ko. New York: Abbeville Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-89659-774-7.

And so the first Chinese dictionary was born, the Sān Chāng, containing 3,300 characters

- ^ Xigui, Qiu (2000). Chinese writing. Society for the study of Early China. p. 103. ISBN 1-55729-071-7. OCLC 470162569.

- ^ Z. "Chinese Calligraphy". Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2018.

- ^ 康熙字典 [Kangxi Zidian] (in Chinese). 1716. p. 41.. See, for example, the radicals 卩, 厂, or 广. The 2007 common shape for those characters does not clearly show the stroke order, but old versions, visible on p. 41, clearly allow the stroke order to be determined.

- ^ Li, J., ed. (n.d.). ""Four treasures of Study" tour". Retrieved 30 May 2018.

- ^ Suzuki, Yuuko (2005). An introduction to Japanese calligraphy. Tunbridge Wells: Search. ISBN 978-1-84448-057-9.

- ^ "Philippine Paleographs (Hanunoo, Buid, Tagbanua and Pala'wan) – United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization". www.unesco.org.

- ^ "'Educate first': Filipinos react to Baybayin as national writing system". 27 April 2018.

- ^ "House panel approves Baybayin as national writing system". SunStar. 24 April 2018.

- ^ "5 things to know about PH's pre-Hispanic writing system". ABS-CBN News. 25 April 2018.

- ^ Stanley Baldwin O. See (15 August 2016). "A primer on Baybayin". gmanetwork.com.

- ^ Michael Wilson I. Rosero (26 April 2018). "The Baybayin bill and the never ending search for 'Filipino-ness'". CNN Philippines. Archived from the original on 5 May 2020.

- ^ "10 Perfectly Awesome Calligraphers You Need To Check Out". brideandbreakfast.ph. 12 August 2015.

- ^ Deni Rose M. Afinidad-Bernardo (1 June 2018). "How to ace in script lettering". philstar.com.

- ^ VietnamPlus (9 February 2022). "Vietnamese Traditional Calligraphy During Tet | Festival | Vietnam+ (VietnamPlus)". VietnamPlus. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ^ Salomon, Richard (1998). Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the Other Indo-Aryan Languages. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195099843.

- ^ Mitter, Partha (2001). Indian Art. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. p. 100. ISBN 9780192842213.

- ^ Sabard, V.; Geneslay, V.; Rébéna, L. (2004). Calligraphie latine: Initiation [Latin calligraphy: Introduction] (in French) (7th ed.). Paris: Fleurus. pp. 8–11. ISBN 978-2-215-02130-8.

- ^ "Insular Manuscripts: Paleography, Section 6: Language on the Page in Insular Manuscripts, Layout and Legibility". Virtual Hill Museum & Manuscript Library. Archived from the original on 19 November 2018. Retrieved 30 May 2018.

- ^ a b c de Hamel 2001a.

- ^ Knight, Stan (1998). Historical scripts: from Classical Times to the Renaissance (2nd, Corrected ed.). New Castle, Del: Oak Knoll Press. pp. 9–10. ISBN 9781884718564.

- ^ Trinity College Library Dublin 2006; Walther & Wolf 2005; Brown & Lovett 1999: 40; Backhouse 1981[full citation needed]

- ^ Jackson 1981: 641[full citation needed]

- ^ Walther & Wolf 2005; de Hamel 1994: 46–481[full citation needed]

- ^ de Hamel 1994: 461[full citation needed]

- ^ a b Lovett, Patricia (2000). Calligraphy and Illumination: A History and Practical Guide. Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0-8109-4119-9.

- ^ a b c d Joyce Irene Whalley (c. 1980). The Art of Calligraphy, Western Europe & America.

- ^ Brown, M.P. (2004). Painted Labyrinth: The World of the Lindisfarne Gospel (Revised ed.). British Library.

- ^ The Bible: New Living Translation. Tyndale House Publishers. 2000.

- ^ "CALLIGRAPHY IN ISTANBUL | History of Istanbul". istanbultarihi.ist. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- ^ de Hamel 1986

- ^ Gilderdale 1999; Gray 1971[full citation needed]

- ^ a b "The Legacy of Edward Johnston". The Edward Johnston Foundation.

- ^ Cockerell 1945; Morris 1882

- ^ "Font Designer — Edward Johnston". Linotype GmbH. Retrieved 5 November 2007.

- ^ "The Eric Gill Society: Associates of the Guild: Edward Johnston". Archived from the original on 10 October 2008.

- ^ Gilderdale 1999[full citation needed]

- ^ Baines & Dixon 2003: 81[full citation needed]

- ^ Tresser 2006

- ^ Whitley 2000: 90[full citation needed]

- ^ Herringham 1899[full citation needed]

- ^ Jackson 1981: 81[full citation needed]

- ^ Hewitt 1944–1953[full citation needed]

- ^ Cinamon 2001; Kapr 1991[full citation needed]

- ^ Henning, W.E. (2002). Melzer, P. (ed.). An Elegant Hand: The Golden Age of American Penmanship and Calligraphy. New Castle, Delaware: Oak Knoll Press. ISBN 978-1-58456-067-8.

Works cited

[edit]- Benson, John Howard; Carrey, Arthur Graham (1940). The Elements of Lettering. Newport, Rhode Island: John Stevens.

- Benson, John Howard (1955). The First Writing Book: an English translation & fascimile text of Arrighi's Operina, the first Manual of the chancery hand. London: Oxford University Press.

- de Hamel, C. (2001a). The Book: A History of the Bible. Phaidon Press.

- Diringer, David (1968). The Alphabet: A Key to the History of Mankind. Vol. 1 (3rd ed.). London: Hutchinson & Co. p. 441.

- Fairbank, Alfred (1975). Augustino Da Siena, the 1568 edition of his writing book in fascimile. London: The Merrion Press. ISBN 0-87923-128-9.

- Fraser, M.; Kwiatowski, W. (2006). Ink and Gold: Islamic Calligraphy. London: Sam Fogg Ltd.

- Gaze, Tim; Jacobson, Michael, eds. (2013). An Anthology of Asemic Handwriting. Brooklyn, NY: Punctum Books. ISBN 978-90-817091-7-0. OCLC 1100489411.

- Kosack, Wolfgang (2014). Islamische Schriftkunst des Kufischen: geometrisches Kufi in 593 Schriftbeispielen (in German). Basel: Verlag Christoph Brunner. ISBN 978-3-906206-10-3. OCLC 894692503.

- Johnston, E. (1909). "Plate 6". Manuscript & Inscription Letters: For schools and classes and for the use of craftsmen. San Vito Press & Double Elephant Press. 10th Impression

- Marns, F.A (2002). Various, copperplate and form. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Shepherd, Margaret (2013). Learn World Calligraphy: Discover African, Arabic, Chinese, Ethiopic, Greek, Hebrew, Indian, Japanese, Korean, Mongolian, Russian, Thai, Tibetan Calligraphy, and Beyond. Crown Publishing Group. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-8230-8230-8.

- Mediavilla, Claude (2006). Histoire de la calligraphie française (in French). Paris: Michel. ISBN 978-2-226-17283-9.

- Ogg, Oscar (1954). Three classics of Italian Calligraphy, an unabridged reissue of the writing books of Arrighi, Giovanni Antonio Tagliente & Palatino, with an introduction. New York, US: Dover Publications.

- Osley, A. S., ed. (1965). Calligraphy and Paleography, Essays presented to Alfred Fairbank on his 70th birthday. New York: October House Inc.

- Schimmel, Annemarie (1984). Calligraphy and Islamic Culture. New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-7830-2.

- Wolpe, Berthold (1959). A Newe Writing Booke of Copies, 1574: A fascimile of a unique Elisabethan Writing book in the Bodleian Library Oxford'. London: Lion and Unicorn Press.

- Zapf, H. (2007). Alphabet Stories: A Chronicle of technical developments. Rochester, NY: Cary Graphic Arts Press. ISBN 978-1-933360-22-5.

External links

[edit]- Calligraphy alphabets, a list of major historical scripts (simplified version) at Lettering Daily

- French Renaissance Paleography This is a scholarly maintained site that presents over 100 carefully selected French manuscripts from 1300 to 1700, with tools to decipher and transcribe them.

![Sample showing Nastaliq proportional rules (Persian and Urdu languages)[citation needed]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0c/Nastaliq-proportions.jpg/173px-Nastaliq-proportions.jpg)