Cartesian theater

"Cartesian theater" is a derisive term by philosopher and cognitive scientist Daniel Dennett, made known in his 1991 book Consciousness Explained, to refer pointedly to a defining aspect of what he calls Cartesian materialism, which he considers to be the often unacknowledged remnants of Cartesian dualism in modern materialist theories of the mind.

Dennett's former teacher Gilbert Ryle, in his book The Concept of Mind (1949), had also ridiculed the conception of the mind as a "private theater" or "second theater" in Cartesian dualism.[1]

Overview

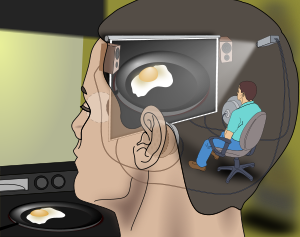

[edit]Descartes originally claimed that consciousness requires an immaterial soul, which interacts with the body via the pineal gland of the brain. Dennett says that, when the dualism is removed, what remains of Descartes' original model amounts to imagining a tiny theater in the brain where a homunculus (small person), now physical, performs the task of observing all the sensory data projected on a screen at a particular instant, making the decisions and sending out commands (see Homunculus argument).

The term "Cartesian theater" was brought up in the context of the multiple drafts model that Dennett posits in Consciousness Explained (1991):

Cartesian materialism is the view that there is a crucial finish line or boundary somewhere in the brain, marking a place where the order of arrival equals the order of "presentation" in experience because what happens there is what you are conscious of. ... Many theorists would insist that they have explicitly rejected such an obviously bad idea. But ... the persuasive imagery of the Cartesian Theater keeps coming back to haunt us—laypeople and scientists alike—even after its ghostly dualism has been denounced and exorcized.[2]

See also

[edit]- Circular reasoning

- Global workspace theory

- Inside Out

- Münchhausen trilemma

- The Numskulls

- Personal horizon

- Purusha

- Turtles all the way down

- Vertiginous question

Notes

[edit]- ^ Caston, Victor (2021). "Aristotle and the Cartesian theatre" (PDF). In Gregoric, Pavel; Fink, Jakob Leth (eds.). Encounters with Aristotelian Philosophy of Mind. New York: Routledge. pp. 169–220 (footnote 1). doi:10.4324/9781003008484-11. ISBN 9780367439132. OCLC 1223014825.

- ^ Dennett, Daniel C. (1991). Consciousness Explained. New York: Little, Brown & Co. p. 107. ISBN 0-316-18065-3. OCLC 36182395.

Further reading

[edit]- Carruthers, Peter (2000). "Fragmentary consciousness and the Cartesian theatre". Phenomenal Consciousness: A Naturalistic Theory. Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 297–324. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511487491.012. ISBN 0521781736. OCLC 43287175.

- Dennett, Daniel C. (1982). "Styles of mental representation". Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society. 83: 213--226. JSTOR 4545000. Includes an early use of the term "Cartesian theater".

- Dennett, Daniel C.; Kinsbourne, Marcel (June 1992). "Time and the observer: the where and when of consciousness in the brain". Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 15 (2): 183–201, commentary and response 201–247. doi:10.1017/S0140525X00068229. Includes open peer commentary and a reply by the authors.

- Dolega, Krzysztof; Dewhurst, Joe (2015). "Curtain call at the Cartesian theatre" (PDF). Journal of Consciousness Studies. 22 (9–10): 109–128. Responds to Hobson & Friston (2014).

- Gobert, R. Darren (2013). The Mind-Body Stage: Passion and Interaction in the Cartesian Theatre. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. doi:10.11126/stanford/9780804786386.001.0001. ISBN 9780804786386. OCLC 830683608.

- Gray, Jeffrey Alan (2004). "From Cartesian theatre to global workspace". Consciousness: Creeping up on the Hard Problem. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 149–170. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198520917.003.0011. ISBN 0198520905. OCLC 55970336.

- Hobson, J. Allan; Friston, Karl J. (2014). "Consciousness, dreams, and inference: the Cartesian theatre revisited" (PDF). Journal of Consciousness Studies. 21 (1–2): 6–32.

- Hobson, J. Allan; Friston, Karl J. (2016). "A response to our theatre critics" (PDF). Journal of Consciousness Studies. 23 (3–4): 245–254. Responds to Dolega & Dewhurst (2015).

- Lormand, Eric (1994). "Qualia! (now showing at a theater near you)". Philosophical Topics. 22 (1/2): 127–156. JSTOR 43154656.

- Slezak, Peter (2023). Spectator in the Cartesian Theater: Where Theories of Mind Went Wrong Since Descartes. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. ISBN 9781666923759. OCLC 1377716149.