Peter W. Rodino

Peter Rodino | |

|---|---|

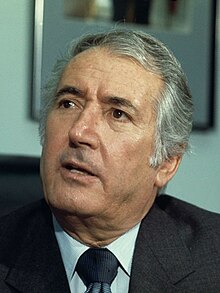

Rodino in 1974 | |

| Chair of the House Judiciary Committee | |

| In office January 3, 1973 – January 3, 1989 | |

| Preceded by | Emanuel Celler |

| Succeeded by | Jack Brooks |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from New Jersey's 10th district | |

| In office January 3, 1949 – January 3, 1989 | |

| Preceded by | Fred A. Hartley Jr. |

| Succeeded by | Donald M. Payne |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Pelligrino Rodino Jr. June 7, 1909 Newark, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Died | May 7, 2005 (aged 95) West Orange, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouses | Marianna Stango

(m. 1941; died 1980)Joy Judelson (m. 1989) |

| Children | 2 |

| Education | Rutgers University, Newark (BA, LLB) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1941–1946 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

| Awards | Bronze Star |

| Watergate scandal |

|---|

|

| Events |

| People |

Peter Wallace Rodino Jr. (born Pelligrino Rodino Jr.; June 7, 1909 – May 7, 2005) was an American politician who was a member of the United States House of Representatives from 1949 to 1989. A liberal Democrat, he represented parts of Newark, New Jersey and surrounding Essex and Hudson.[a] He was the longest-serving member of the House of Representatives from New Jersey until passed by Chris Smith in 2021.

Rodino rose to prominence as the chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, where he oversaw the 1974 impeachment hearings against President Richard Nixon that eventually led to the president's resignation.

Early life

[edit]Rodino was born Pelligrino Rodino Jr. in the North Ward of Newark, New Jersey, on June 7, 1909. His father, Pelligrino Rodino (1883–1957), was born in Atripalda, a town in the province of Avellino, in a region of southern Italy known as Campania. Rodino Sr. emigrated to the United States around 1900 and worked as a machinist in a leather factory, as a cabinet maker and carpenter, and for thirty years as a toolmaker for General Motors (Hyatt Roller Bearing). His mother, Giuseppina (Margaret) Girard (1884–1913), was born in Newark. Pelligrino and Giuseppina were married in 1900. Pelligrino Rodino Jr., whose name was later Americanized to Peter, was the youngest of three children.[1] Giuseppina Rodino died in 1913 of tuberculosis, when Rodino was 4;[2] his father later married Antonia (Gemma) DeRobertis (Died 1944), the widow of Michael Paladino.[1]

He attended McKinley Grammar School, graduating in February 1922. He attended Barringer High School. He went to college at the University of Newark and earned a law degree at the Newark Law School; both are now part of Rutgers University.[3] His speech was badly affected by a childhood bout of diphtheria, and he conducted his own speech therapy, spending hours "reciting Shakespeare through a mouth full of marbles". Rodino endured ten years of menial jobs while studying at night for a law degree at the New Jersey Law School. He worked for the Public Service Railroad and Transportation Company. Rodino worked as an insurance salesman and at Pennsylvania Railroad. He also worked at Ronson Art Metal Works making cigarette lighters. He taught public speaking and citizenship in Newark. He also worked as a songwriter.[1]

Rodino served in the administration of President Franklin Roosevelt as an appeals agent for the Newark Draft Board. While the post exempted Rodino from the draft, he enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1941, and served from 1942 to 1946. Rodino attended the British Officers Training University of England[citation needed] and was commissioned as a second lieutenant. He was assigned to the First Armored Division in North Africa, and later in Italy with the Military Mission Italian Army, a joint Allied force. Due to his fluency in Italian, he was named the adjutant to the Commanding General of Rome.[1] He earned a Bronze Star for service in Italy and North Africa; he was discharged with the rank of captain.[3]

State assembly candidate

[edit]In 1940, Rodino made his first bid for public office as a Democratic candidate for the New Jersey General Assembly from Essex County.[4] He lost the general election.[5]

U.S. Congressman

[edit]In 1946, after World War II, Rodino ran for Congress against nine-term Republican incumbent Fred A. Hartley Jr. Hartley was nationally prominent as the House sponsor of the Labor Management Relations Act of 1947, known as Taft–Hartley. Hartley won by 5,730 votes, 44,619 (52.48%) to 38,889 (45.74%).[6]

Hartley declined to seek re-election in 1948 and Rodino became a candidate for the open 10th district congressional seat. He was unopposed in the Democratic primary.[7] In the general election, he faced Republican Anthony Giuliano, who had served as a State Assemblyman and as an Assistant U.S. Attorney. Rodino had the benefit of running on a ticket with president Harry Truman, who carried Essex and Hudson counties. Truman, campaigning in Newark on October 6, 1948, endorsed Rodino, saying: "That means that here in Newark you're going to send Rodino to the Congress, and Hugh Addonizio and Harry Dudkin to the House of Representatives. Every one of these men deserves your support. They will fight your battle in Washington, and how that fight needs to be made nobody knows better than I do. They will fight your battle there, and men like them all over the Nation will be fighting that battle—and will win that battle if you're behind us—the battle for the people, a fight which started with Jefferson, continued with Jackson, was won by Franklin Roosevelt in 1934."[8] Rodino won by 5,800 votes, 58,668 (50.72%) to 52,868 (45.70%).[9]

Seeking a second term in 1950, Rodino faced Republican William H. Rawson, a six-term Essex County Freeholder.[10] Rodino won by 21,819 votes: 60,432 (61.02%) to 38,613 (38.99%).[11]

In 1952, Rodino faced a national political environment that was decidedly Republican, and GOP presidential candidate Dwight Eisenhower carried Rodino's district by a large margin.[12] But Rodino won a third term by 20,872 votes against Republican Alexander Matturri, 78,612 (56.87%) to 57,740 (41.77%).[13]

Rodino defeated Republican William E. McGlynn, a two-term Councilman from Kearny, New Jersey who described himself as a "middle of the road Eisenhower Republican"[14] by 26,328 votes, 62,384 (63.37%) to 36,056 (36.63%) in 1954.[15]

In 1956, Rodino was re-elected by 15,550 votes, 71,311 (56.12%) to 55,761 (43.88%),[16] against Republican G. George Addonizio, a first time candidate who had the same last name as a popular Democratic Congressman who was seeking re-election in a neighboring Essex County congressional district; George Addonizio and Hugh Addonizio were not related. George Addonizio cast himself as an Eisenhower Republican in a year the popular Republican president carried Rodino's district by a wide margin in his re-election campaign.[17] This was the last time Rodino's general election percentage would fall below 60%. In a 1958 rematch with Addonizio, he won by 27,536 votes, 60,482 (63.90%) to 32,946 (34.81%).[18] Rodino won 65% in 1960 and 73% in 1962.[19]

He was re-elected in 1960 with 65% against Alphonse A. Miele, and in 1962 with 73% against Dr. Charles Allen Baretski, the Director of the Newark Public Library and the founder of the Institute of Polish Culture at Seton Hall University. In 1964, he defeated former Bloomfield Councilman Raymond W. Schroeder[20] with 74% of the vote.

Rodino faced his first African American opponent in 1966, when Earl Harris, a Republican Essex County Freeholder (and future Newark city council president) ran against him. In a Democratic landslide year nationally and in New Jersey, Rodino beat Harris with 64% of the vote.[19]

He was re-elected in 1968 (64% against Dr. Celestino Clemente, a surgeon), 1970 (70% against Griffin H. Jones,[21] a Montclair lawyer), 1972 (80% against bakery owner Kenneth Miller[22]), 1974 (81% against Newark-South Ward Republican Chairman John R. Taliaferro), 1976 (83% against Tony Grandison), 1978 (86% against John L. Pelt, an auto salesman), 1980 (85% against East Orange businessman Everett Jennings), 1982 (83% against Tim Lee), 1984 (84% against conservative activist Howard E. Berkeley), and 1986 (96%, with no Republican in the race).

For many years, Rodino shared a Washington apartment with Hugh Addonizio, a fellow Newark Democrat who was also elected to Congress in 1948 as a young World War II veteran. After Addonizio left Congress to become Mayor of Newark in 1962, Rodino became roommates with Addonizio's successor, Democratic labor leader Joseph Minish.[23] Rodino returned to his district every weekend.[2]

Democratic primary challenges

[edit]From the 1970s onward, Rodino's main challenge was in the Democratic primary. This was mainly because the cities anchoring his district, such as Newark, East Orange, Irvington, and Orange, saw substantial growth of African American populations as white voters moved to the suburbs. In 1972, the 10th district was redrawn as a black majority district.[24] Rodino, who had spent a career fighting on behalf of civil rights, was now a white congressman in a district that was drawn to increase African American representation in Congress.

In 1972, Rodino faced his first serious challenge from an African American candidate in the Democratic primary. He considered moving into the neighboring 11th district, which lost its black, urban municipalities in redistricting and instead included suburban Essex County towns (including a slice of Rodino's former territory); this would have forced a primary against Rodino's colleague (and Capitol Hill roommate), Joseph Minish.[23] While many of Rodino's political advisers urged him to run in the 11th, Rodino decided to remain in the 10th and face two African American candidates: East Orange Mayor William S. Hart and former Assemblyman George C. Richardson of Newark[25] Rodino beat Hart by 13,000 votes, 37,650 (57%) to 24,118 (37%). Richardson finished third with 3,086 votes (5%) and Wilburt Kornegy received 718 votes (1%).[26]

Rodino faced another serious primary challenge in 1980, this time against Donald M. Payne, a former Essex County Freeholder who had carried the 10th district in his campaign for the Democratic nomination for Essex County Executive in 1978.[27] At this point, Rodino was a national political figure and beat Payne by 17,118 votes, 26,943 (62.17%) to 9,825 (22.67%). Former Newark Municipal Court Judge Golden Johnson finished third with 5,316 votes (12.27%), followed by 1,251 (2.89%) for Rev. Russell E. Fox, a former Essex County Freeholder and East Orange school board member.[28]

Payne ran again in 1986, and had the endorsements of newly elected Newark Mayor Sharpe James and the Rev. Jesse Jackson. Rodino promised to retire in 1988 and beat Payne by 9,920 votes, 25,136 (59.49%) to 15,216 (36.01%).[29] Payne was elected in 1988 and was re-elected eleven times without substantive opposition, never dropping below 75% of the vote and died in office on March 6, 2012.[30][31] [32]

Legislative record

[edit]

During his first term, Rodino was a member of the House Veterans Affairs Committee. After winning re-election in 1950, he was assigned a seat on the House Judiciary Committee. He worked to enact legislation to assure equal rights, reform immigration policy and public safety. He was the author of majority reports on civil rights legislation of 1957, 1960, 1964, and 1968, was the author of Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Rodino was the floor manager of the 1966 Civil Rights Act. He was the Co-Sponsor of what became the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968, and authored the bill that designated Columbus Day as a national holiday. From 1971 to 1973 he was the Chairman of the Immigration, Citizenship and Nationality Subcommittee and played a key role in passing the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986.[1]

Throughout his 40 years in Congress, Rodino held fast to a liberal agenda. He stopped the proposed constitutional amendments that would ban abortion, allow organized prayer in the public schools, and prohibit busing to achieve school integration. Still, he was one of the last liberal Members of Congress to oppose the Vietnam War. He was viewed as an expert on immigration and bankruptcy law. He was a strong supporter of fair-housing legislation, and a staunch ally of organized labor.[2]

In 1973, Rodino voted against the confirmation of Gerald Ford as vice president as a protest against the policies of the Nixon administration.[2]

In 1975, Rodino received the U.S. Senator John Heinz Award for Greatest Public Service by an Elected or Appointed Official, an award given out annually by Jefferson Awards.[33]

U.S. Senate campaign

[edit]Rodino nearly gave up his House seat after three terms to seek the Democratic nomination for the United States Senate in 1954, when incumbent GOP Senator Robert C. Hendrickson was retiring after one term. Democrats believed they had a chance to pick up the open Senate seat and party bosses decided they would clear the field for a single candidate, avoiding a primary.[34] Rodino actively sought support for the Senate seat,[35] but Democrats instead went with another Congressman, Charles R. Howell.[36]

House leadership

[edit]

Rodino was the Assistant Majority Whip of the House from 1965 to 1972, and served as a member of the Democratic Steering & Policy Committee during the same years. He was the Senior Member of the House Select Committee on Narcotics Abuse and Control in 1977 and from 1979 to 1988. He was a delegate to the North Atlantic Assembly where he was chaired the Scientific and Technical Committee; to the Working Group on the Control of Narcotics from 1962 to 1972; and to the Intergovernmental Committee for European Migration dealing with refugee problems from 1962 to 1972.[1] He was also a member of the Congressional Committees Investigating The Iran-Contra Affair in 1987.[37]

House Judiciary Committee chairman

[edit]Rodino became chairman of the House Judiciary Committee in January 1973, at the start of the 93rd Congress. He succeeded Emanuel Celler, a 50-year incumbent, who had been defeated for renomination in the 1972 Democratic primary election.

Later in 1973, after President Richard Nixon fired Watergate Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox on October 20, in what became known as the "Saturday Night Massacre", numerous presidential impeachment related resolutions were proposed in the House. Speaker of the House Carl Albert referred them to the Judiciary Committee.[38] The resultant impeachment inquiry and public hearings put Rodino, who until then had kept a low profile in Congress, front and center in the political limelight. "If fate had been looking for one of the powerhouses of Congress, it wouldn't have picked me", he told a reporter at the time.[39]

The committee spent eight months gathering evidence and pressing the president to comply with subpoenas for White House tape recordings and documents.[2] In 2005, John Doar, who was Special Counsel to the Judiciary Committee during the Watergate hearings, said of Rodino:

He was able to impose discipline on the staff. He insisted that there be no leaks to the press. There were no leaks to the press. He insisted that it be bipartisan, it not be partisan. There was no partisanship on the staff. In fact, it was remarkably non-partisan. And that is the result of good leadership. And although Congressman Rodino was a quiet man, he had the knack of leading, of managing, and he did it very well, in my opinion.[40]

As the Judiciary Committee prepared to vote on the first article of impeachment in July 1974, Rodino said: "We have deliberated. We have been patient. We have been fair. Now the American people, the House of Representatives and the Constitution and the whole history of our republic demand that we make up our minds." The committee, with six Republicans joining the Democratic majority, passed three of the five articles of impeachment.[39] In a 1989 interview with Susan Stamberg of National Public Radio, Rodino recalled that after the committee finished its work on the impeachment articles, he went to a room in back of the committee chambers, called his wife and cried. He also stated:

Notwithstanding the fact that I was Democrat, notwithstanding the fact that there were many who thought that Rodino wanted to bring down a president as a Democrat, you know, he was our president. And this is our system that was being tested. And here was a man who had achieved the highest office that anyone could gift him with, you know. And you're bringing down the presidency of the United States, and it was a sad, sad commentary on our whole history and, of course, on Richard Nixon.[40]

Rodino presided over Gerald Ford's December 1973 vice presidential confirmation hearing before the House Judiciary Committee.[2] He also was appointed twice by the House as one of the managers to conduct (prosecute) impeachment trials against U.S. federal judges: Nevada judge Harry Claiborne in 1986 (for tax evasion) and Florida judge (and later congressman) Alcee Hastings in 1988 (for perjury). While he served during the trial of Claiborne, he was replaced at the start of the 101st United States Congress as an impeachment manager for the Hastings trial, before the trial had begun.[41]

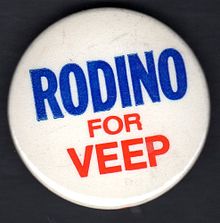

Vice presidential candidate

[edit]

Rodino emerged as a possible running mate for Jimmy Carter in 1976. About 50 House members signed a petition urging Carter to pick Rodino,[42] and then-House Majority Leader Tip O'Neill told Charles Kirbo (the Atlanta lawyer that was heading up Carter's vice presidential search) that Rodino would be his best choice. O'Neill said that Rodino was a Catholic from a northeastern state who could bring middle class Italians back into the Democratic fold.[43]

After Kirbo finished vetting possible candidates, Carter created a short list of seven—Rodino, and Senators Walter Mondale, Frank Church, Henry Jackson, John Glenn, Edmund Muskie, and Adlai Stevenson III. In July, before Carter made his choice, Rodino withdrew his name from consideration. He cited his age (67) and a recurring case of glaucoma that he felt might strain his ability to campaign.[44]

Instead, Rodino was asked to give the nominating speech for Carter at the Democratic National Convention in New York. "With honest talk and plain truth, Jimmy Carter has appealed to the American people. His heart is honest, and the people will believe him. His purpose is right, and the people will follow him," Rodino said. "As he has brought a united South back into the Democratic Party, he will bring a united Democratic Party back into the leadership of America and a united America back to a position of respect and esteem in the eyes of the world."[45]

In 1972, 57 delegates to the Democratic National Convention voted for Rodino for vice president instead of Thomas Eagleton, who was picked by nominee George McGovern.[46]

Family

[edit]Rodino married Marianna (Ann) Stango in 1941. They had two children: Margaret (Peggy) Stanziale and Peter W. Rodino III. Peggy Stanziale married Charles A. Stanziale Jr., whose father had served as a Democratic State Assemblyman in 1932 and later as an Assistant U.S. Attorney. Marianna Rodino died on December 3, 1980, at age 70.[47] In 1989, he married Joy Judelson, who had worked on Rodino's congressional staff from 1963 until 1969, when she left to go to law school. They were married until his death in 2005.

Retirement

[edit]On March 15, 1988, Rodino announced that he would retire from Congress after 20 terms. "Our journey together has been a long and fulfilling one," Rodino said in a statement.[48] He left the House in January 1989 and was replaced by Payne, who became the first African American Congressman from New Jersey.

On November 4, 1978, Vice-President Walter Mondale attended the dedication of the Peter W. Rodino Federal Building in Newark.

After leaving congress, he became a Distinguished Visiting Professor of Constitutional Law at Seton Hall University Law School in Newark. He was a member of the faculty from 1989 until his death in 2005. "Between 1990 and 1999, he taught two seminars each year, providing students a unique opportunity to actively participate in research, study, and discussion of some of the many areas of law affected by his time in public office. Enrollment was limited to 25 students, and the courses were fully subscribed. Most of the term was taken up with traditional small class discussion of pertinent issues. Each student also undertook a research paper on a specific topic, with the research results being presented in the seminar in the latter stages of the term. Critique and commentary was provided by Professor Rodino. The first term seminar concentrated on Civil Rights and Immigration, including in particular the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1986 Immigration Reform & Control Act. The second term seminar dealt with Watergate and the Iran Contra Affair. These courses were co-taught with Professors Gil Carrasco and E. Judson Jennings," according to Seton Hall. "While at Seton Hall, Professor Rodino participated in many significant programs and events, including a Celebration of the Bicentennial of the Bill of Rights. He also wrote several important law review articles on the Ninth Amendment, the Special Prosecutor Statute, the Preamble to the Constitution, and the Presidency."[1]

In 1998, when the House was considering articles of impeachment against president Bill Clinton, Rodino urged congressmen to be "cautious, restrained and non-partisan when weighing whether such an investigation is warranted". He said: "Even the thought of impeachment is a question that should be considered ever so judiciously, especially when it comes to an issue that wracks a country, a constitutional crisis, impeachment is not to be considered lightly."[49]

He died on May 7, 2005, of congestive heart failure at the age of 95 at his home in West Orange, New Jersey.[3] He lay in state at Seton Hall Law Chapel and the funeral mass was celebrated at St. Lucy's Church in Newark. Burial took place at Gate of Heaven Cemetery in East Hanover, New Jersey.[1]

Electoral history

[edit]New Jersey General Assembly (1940)

[edit]12 Seats Elected At-Large from Essex County[5]

| Winner | Party | Votes | Loser | Party | Votes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Olive C. Sanford | Republican | 175,280 | Peter W. Rodino Jr. | Democrat | 132,393 |

U.S. House of Representatives

[edit]General elections

[edit]| Year | Democrat | Votes | Republican | Votes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1946 | Peter W. Rodino | 38,889 | Fred A. Hartley Jr. (Incumbent) | 44,619 |

| 1948 | Peter W. Rodino | 58,668 | Anthony Giuliano | 52,868 |

| 1950 | Peter W. Rodino | 60,432 | William H. Rawson | 38,613 |

| 1952 | Peter W. Rodino | 78,612 | Alexander Matturri | 57,740 |

| 1954 | Peter W. Rodino | 62,384 | William E. McGlynn | 36,056 |

| 1956 | Peter W. Rodino | 71,311 | G. George Addonizio | 55,761 |

| 1958 | Peter W. Rodino | 60,482 | G. George Addonizio | 32,946 |

| 1960 | Peter W. Rodino | 84,859 | Alphonse A. Miele | 43,238 |

| 1962 | Peter W. Rodino | 62,616 | Charles A. Baretski | 22,819 |

| 1964 | Peter W. Rodino | 92,488 | Raymond W. Schroeder | 31,306 |

| 1966 | Peter W. Rodino | 71,699 | Earl Harris | 36,508 |

| 1968 | Peter W. Rodino | 89,109 | Celestino Clemente | 47,989 |

| 1970 | Peter W. Rodino | 71,003 | Griffith H. Jones | 30,460 |

| 1972 | Peter W. Rodino | 94,308 | Kenneth C. Miller | 23,949 |

| 1974 | Peter W. Rodino | 53,094 | John R. Taliaferro | 9,936 |

| 1976 | Peter W. Rodino | 88,245 | Tony Grandison | 17,129 |

| 1978 | Peter W. Rodino | 55,074 | John L. Pelt | 8,066 |

| 1980 | Peter W. Rodino | 76,154 | Everett J. Jennings | 11,778 |

| 1982 | Peter W. Rodino | 76,684 | Timothy Lee Jr. | 14,551 |

| 1984 | Peter W. Rodino | 111,244 | Howard E. Berkeley | 21,712 |

| 1986 | Peter W. Rodino | 46,666 | Unopposed |

Primary elections

[edit]| Year | Democrat | Votes |

|---|---|---|

| 1966 | Peter W. Rodino | 14,254[50] |

| 1966 | William J. Clark | 1,027[50] |

| 1972 | Peter W. Rodino | 37,650 |

| 1972 | William S. Hart | 24,118 |

| 1972 | George C. Richardson | 3,086 |

| 1972 | Wilbert J. Kornegay | 718 |

| 1974 | Peter W. Rodino | 19,121 |

| 1974 | Michael Giordano | 2,330 |

| 1980 | Peter W. Rodino | 26,943 |

| 1980 | Donald M. Payne | 9,825 |

| 1980 | Golden E. Johnson | 5,316 |

| 1980 | Russell E. Fox | 1,251 |

| 1982 | Peter W. Rodino | 28,587 |

| 1982 | Alan Bowser | 5,010 |

| 1984 | Peter W. Rodino | 42,109 |

| 1984 | Arthur S. Jones | 10,294 |

| 1984 | Thelma I. Tyree | 2,779 |

| 1986 | Peter W. Rodino | 25,136 |

| 1986 | Donald M. Payne | 15,216 |

| 1986 | Pearl Hart | 967 |

| 1986 | Arthur S. Jones | 931 |

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h "The Rodino Archives". Seton Hall University. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f Wood, Anthony R.; Horvitz, Paul (May 8, 2005). "Ex-congressman Peter Rodino, 95, dies The N.J. Democrat headed impeachment hearings that led Nixon to resign". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Archived from the original on January 15, 2015. Retrieved January 15, 2015.

- ^ a b c Kaufman, Michael T. "Peter W. Rodino Dies at 96; Led House Inquiry on Nixon", The New York Times, May 8, 2005. Accessed November 25, 2007. "Peter W. Rodino Jr., an obscure congressman from the streets of Newark who impressed the nation by the dignity, fairness, and firmness he showed as chairman of the impeachment hearings that induced Richard M. Nixon to resign as president, died yesterday at his home in West Orange, N.J. He was 95."

- ^ "Results of the Primary Election" (PDF). New Jersey Division of Elections. State of New Jersey. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ^ a b Legislative Manual of New Jersey. Trenton, New Jersey: Joseph J. Gribbons. 1941.

- ^ "Our Campaigns". www.ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ^ "Results of the Primary Election" (PDF). New Jersey Division of Elections. State of New Jersey. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ^ "Rear Platform and Other Informal Remarks in Pennsylvania and New Jersey". www.trumanlibrary.org. Harry S. Truman Library & Museum. Archived from the original on February 18, 2015. Retrieved December 2, 2014.

- ^ "Our Campaigns". www.ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ^ "PARTY FIGHTS MARK JERSEY PRIMARIES; Contests in Half of the State's 14 Congressional Districts Draw Wide Attention Record Hudson Vote Seen Contests in Essex County". The New York Times. April 16, 1950.

- ^ "Our Campaigns". www.ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ^ Legislative Manual of New Jersey. Trenton, New Jersey: Joseph J. Gribbons. 1953.

- ^ "Our Campaigns". www.ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved January 7, 2015.

- ^ Feinberg, Alexander (October 11, 1954). "New Dealer Bidding for His 4th Term in Intensive Campaign". The New York Times.

- ^ "Our Campaigns". www.ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved January 7, 2015.

- ^ "Our Campaigns". www.ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved January 7, 2015.

- ^ Honig, Milton (October 15, 1956). "Rodino Rival in 10th Making First Race for Elective Office; Rodino's Majorities Mount Both Campaign Vigorously". The New York Times.

- ^ "Our Campaigns". www.ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved January 7, 2015.

- ^ a b "Our Campaigns". www.ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ^ Wright, George Cable (October 5, 1964). "Rodino Opposed by a Strong Backer of Goldwater in 10th". The New York Times. Retrieved January 16, 2015.

- ^ "Foe Hopes to Oust Rodino in 10th With Big Ad Campaign". The New York Times. October 9, 1970.

- ^ Ferretti, Fred (October 2, 1972). "Confident Rodino Campaigns in Newark". The New York Times.

- ^ a b "Rodino Is Said to Weigh House Bid in 11th District". The New York Times. April 20, 1972.

- ^ Sullivan, Ronald (April 13, 1972). "Jersey Redistricting Plan Drawn Up by U.S. Court; Redistricting Plan for Jersey Drawn Up by Federal Court". The New York Times.

- ^ Ferretti, Fred (May 31, 1972). "3 Blacks Vie for Rodino's Seat in Newark Race; 3 Blacks Vie for Rodino's House Seat". The New York Times.

- ^ "1972 Primary Election Results" (PDF). New Jersey Division of Elections. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 24, 2013. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ^ Sullivan, Joseph F. (May 25, 1980). "Rodino's Battle One of His Toughest; Rodino Facing His Toughest Fight". The New York Times.

- ^ "Our Campaigns". www.ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ^ "Our Campaigns". www.ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ^ Friedman, Matt. "Pascrell, Donald Payne Jr. win key races in highly contested N.J. Congressional primaries", The Star-Ledger, June 5, 2012. Accessed April 18, 2019.

- ^ Rizzo, Salvador "N.J. 10th Congressional District winner: Donald Payne Jr.", The Star-Ledger, November 6, 2012. Accessed April 18, 2019.

- ^ Donald M. Payne, First Black Elected to Congress From New Jersey, Dies at 77,New York Times, Raymond Hernandez, March 6, 2012. Retrieved April 18, 2019.

- ^ "National - Jefferson Awards Foundation". Archived from the original on November 24, 2010. Retrieved July 17, 2017.

- ^ Edge, Wally (June 3, 2007). "Twenty years before Watergate, Rodino almost gave up his House seat to run statewide". PolitickerNJ.com. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ^ Wright, George Cable (February 7, 1954). "2 DISPUTES WORRY G. O. P. IN JERSEY; Leaders Want Hendrickson to Quit Senate Race, Also Early Peace in Union County". The New York Times.

- ^ "DEMOCRATS NAME HOWELL IN JERSEY; Representative Expected to Accept Senate Nomination by Tomorrow Morning". The New York Times. March 5, 1954.

- ^ Bernstein, Adam (May 8, 2005). "Rep. Peter Rodino, 95". The Washington Post. p. C11.

- ^ Albert, Carl (1990). Little Giant: The Life and Times of Speaker Carl Albert. With Danney Goble. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 363–365. ISBN 0-8061-2250-1.

- ^ a b Shipkowski, Bruce (May 8, 2005). "Peter Rodino Jr., 96: led hearing on Nixon impeachment". The Boston Globe. Retrieved October 25, 2019.

- ^ a b Block, Melissa (May 9, 2005). "Watergate Figure Peter Rodino Dies". npr.org (Podcast). Heard on Morning Edition. Retrieved September 29, 2019.

- ^ "List of Individuals Impeached by the House of Representatives". United States House of Representatives. Archived from the original on December 18, 2019. Retrieved January 15, 2020.

- ^ "48 in the House Support Rodino for Vice President". The New York Times. July 23, 1976.

- ^ McGrory, Mary (June 28, 1976). "Rodino stacks up well for vice president". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 15, 2015.

- ^ Mohr, Charles (July 13, 1976). "Carter Ends Interviews on Running Mate; Carter Ends Interviews on Running Mate and Says That He May Decide by Tonight". The New York Times.

- ^ Apple, R.W. (July 15, 1976). "Carter Wins the Democratic Nomination; Reveals Vice-Presidential Choice Today". The New York Times. Retrieved January 15, 2015.

- ^ "Our Campaigns". www.ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved January 16, 2015.

- ^ "Mrs. Peter W. Rodino". The New York Times. December 4, 1980.

- ^ Sullivan, Joseph F. (March 15, 1988). "Rodino Says He Will Retire In January". The New York Times. Retrieved January 15, 2015.

- ^ "Veterans Of Watergate Urge Restraint". Chicago Tribune. January 24, 1998. Retrieved January 15, 2015.

- ^ a b "Results of the Primary Election, Held September 13, 1966" (PDF). New Jersey Department of State. September 1966.

References

[edit]- ^ Though his district changed shape several times, it always included Newark's North Ward.

- Kaufman, Michael T (2005). "Peter W. Rodino Dies at 96; Led House Inquiry on Nixon". The New York Times. May 8.

External links

[edit]- United States Congress. "Peter W. Rodino (id: R000374)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Picture on cover of Time Magazine

- Rodino and Eleonor Roosevelt during the 1946 congressional campaign against Fred Hartley Archived March 5, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- Rodino campaigning with Harry Truman in 1952 Archived March 6, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- Rodino with John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson

- Rodino standing with Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as President Johnson signs the 1964 Civil Rights Act Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- 1909 births

- 2005 deaths

- 20th-century New Jersey politicians

- American people of Italian descent

- Barringer High School alumni

- Burials at Gate of Heaven Cemetery (East Hanover, New Jersey)

- Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from New Jersey

- Lawyers from Newark, New Jersey

- People from West Orange, New Jersey

- Politicians from Newark, New Jersey

- Rutgers School of Law–Newark alumni

- Seton Hall University School of Law faculty

- Watergate scandal investigators

- Deaths from congestive heart failure

- 20th-century members of the United States House of Representatives