Kanō Eitoku

Kanō Eitoku (狩野 永徳, February 16, 1543 – October 12, 1590) was a Japanese painter who lived during the Azuchi–Momoyama period of Japanese history and one of the most prominent patriarchs of the Kanō school of Japanese painting.

Life and works

[edit]Born in Kyoto, Eitoku was the grandson of Kanō Motonobu[1](1476–1559), an official painter for the Ashikaga shogunate. He showed his talent for painting at an early age, and at the age of 10 he had an audience with the shōgun Ashikaga Yoshiteru alongside Motonobu.

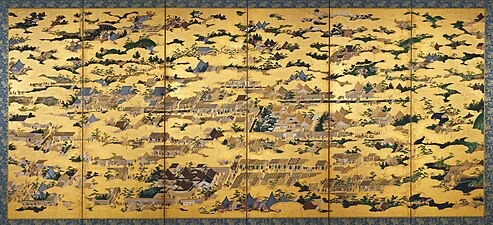

While there are various theories regarding the exact years of creation, in his early twenties, he created two works that are now considered National Treasures: Rakuchū rakugai zu byōbu (洛中洛外図屏風, Views in and around Kyoto) and the fusuma (襖, sliding doors) paintings entitled Kachō zu fusuma (花鳥図襖, Birds and flowers of the four seasons) at Jukō-in, a subtemple of the Daitoku-ji Temple. At a young age, he had acquired skills equivalent to those of Kano Motonobu. He painted the Rakuchū rakugai zu in 1565 at the request of Ashikaga Yoshiteru. Subsequently, Oda Nobunaga acquired the artwork to demonstrate his control over Kyoto and the shogunate, and presented it to Uesugi Kenshin. The Rakuchū rakugai zu is a byōbu (屏風, folding screen) depicting the scenery and customs of Kyoto, and among the designated National Treasures, there are only two: the version known as the Uesugi edition by Kano Eitoku and the Funaki edition by Iwasa Matabei.[2][3]

-

Rakuchū rakugai zu byōbu (洛中洛外図屏風, Views in and around Kyoto, left panel), Yonezawa City Uesugi Museum, National Treasure.

-

Rakuchū rakugai zu byōbu (right panel), Yonezawa City Uesugi Museum, National Treasure.

Eitoku's patrons included Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi. He was hired by Nobunaga at the age of 34. His standing screen, sliding door, wall, and ceiling paintings decorated Nobunaga's Azuchi castle and Hideyoshi's residence in Kyoto and Osaka Castle. Contemporary accounts indicate that Eitoku was one of the most highly sought-after artists of his time, and received many wealthy and powerful patrons. Maintaining the preeminence of the Kanō School was not merely an artistic feat, but an organizational and political one also. Eitoku was able to secure a steady stream of commissions and an efficient workshop of students and assistants, and at one point successfully intercepted a warlord's commission of the rival Hasegawa Tōhaku studio.[4][5]

Style

[edit]His signal contribution to the Kanō repertoire was the so-called "monumental style" (taiga), characterized by bold, rapid brushwork, an emphasis on foreground, and motifs that are large relative to the pictorial space. The traditional account for this style, codified by Eitoku's great-grandson Einō (1631–97) in his History of Japanese Painting (Honcho gashi), is that it resulted partly from the exigencies of Eitoku's busy schedule, and that it embodied the martial and political bravura of the warlords, Nobunaga and Hideyoshi.

Most of his works were destroyed in the turmoil of the Sengoku period. Symbolic representations, like pheasants, phoenixes and trees are often depicted in the works. The pheasant, for example is the national symbol of Japan, are mythological messengers of the sun goddess Amaterasu.[6]

Works

[edit]-

Birds and flowers of the four seasons, Jukō-in, a subtemple of the Daitoku-ji Temple, National Treasure.

-

Chinese guardian lions (Karajishi), Museum of the Imperial Collections, National Treasures.

-

Flowers and Birds of the Four Seasons, Hakutsuru Fine Art Museum.

-

Flowers and Birds of the Four Seasons, Hakutsuru Fine Art Museum.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Kanō Eitoku | Muromachi period, Azuchi-Momoyama period, Momoyama style | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2023-12-21.

- ^ 狩野永徳宇 (in Japanese). Bijutsu Techō. Archived from the original on 6 January 2023. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- ^ 狩野永徳 (in Japanese). The Nagoya Japanese Sword Museum Nagoya Touken World. Archived from the original on 29 May 2023. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- ^ "Cypress tree". www.emuseum.jp. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- ^ Sansom, George (1961). A History of Japan, 1334–1615. Stanford: Stanford University Press. p. 381-382. ISBN 0804705259.

- ^ "cherry-blossom". www.axs.com.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Kanō Eitoku at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Kanō Eitoku at Wikimedia Commons

- National Archives of Japan: Ryukyu Chuzano ryoshisha tojogyoretsu, scroll illustrating procession of Ryukyu emissary to Edo, 1710 (Hōei 7).

- Momoyama, Japanese Art in the Age of Grandeur, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Kanō Eitoku

- Bridge of dreams: the Mary Griggs Burke collection of Japanese art, a catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Kanō Eitoku (see index)