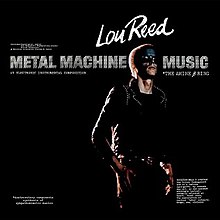

Metal Machine Music

| Metal Machine Music | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | July 1975 | |||

| Genre | Noise | |||

| Length | 64:11 | |||

| Label | RCA Victor | |||

| Producer | Lou Reed | |||

| Lou Reed chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Audio on YouTube | ||||

Metal Machine Music (subtitled *The Amine β Ring) is the fifth studio album by American rock musician Lou Reed. It was recorded on a three-speed Uher machine and was mastered/engineered by Bob Ludwig.[1] It was released as a double album in July 1975 by RCA Records, but taken off the market three weeks later.[2] A radical departure from the rest of his catalog, the Metal Machine Music album features no songs or recognizably structured compositions, eschewing melody and rhythm for modulated feedback and noise music guitar effects, mixed at varying speeds by Reed. Also in 1975, RCA released a Quadrophonic version of the Metal Machine Music recording that was produced by playing it back both forward and backward, and by flipping the tape over.[3]

The album cost Reed his reputation in the music industry while simultaneously opening the door for some of his later, more experimental material and has generally been panned by critics since its release. In 2008, Reed, Ulrich Krieger, and Sarth Calhoun collaborated to tour playing free improvisation inspired by the album as Metal Machine Trio. In 2011, Reed released a remastered version of Metal Machine Music.[4][5]

Style

[edit]A major influence on Reed's recording, for which he tuned all the guitar strings to the same note,[6] was the mid-1960s drone music work of La Monte Young's Theatre of Eternal Music,[7][8] whose members included John Cale, Tony Conrad, Angus MacLise and Marian Zazeela.[9] Both Cale and MacLise were also members of the Velvet Underground (MacLise left before the group began recording).

The Theatre of Eternal Music's discordant sustained notes and loud amplification influenced Cale's subsequent contribution to the Velvet Underground in his use of both discordance and feedback. Recent releases of works by Cale and Conrad from the mid-sixties, such as Cale's Inside the Dream Syndicate series (The Dream Syndicate being the alternative name given by Cale and Conrad to their collective work with Young) testify to the influence this mid-sixties experimental work had on Reed years later.

In an interview with rock journalist Lester Bangs, Reed stated that he "had also been listening to Xenakis a lot." He also claimed that he had intentionally placed sonic allusions to classical works such as Beethoven's Eroica and Pastoral Symphonies in the distortion, and that he had attempted to have the album released on RCA's Red Seal classical label. He repeated the latter claim in a 2007 interview.[10]

Critical reception

[edit]| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Chicago Tribune | |

| Christgau's Record Guide | C+[13] |

| Classic Rock | 5/10[14] |

| Disc | |

| MusicHound Rock | woof![16] |

| Pitchfork | 8.7/10[17] |

| Record Collector | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| Tom Hull – on the Web | C[20] |

Metal Machine Music confounded reviewers and listeners when it was first released. The Stranger's Dave Segal later claimed it was one of the most divisive records ever, challenging both critics and the artist's core audience much like Miles Davis' Agharta album did around the same time.[21]

On release, it was reviewed in Rolling Stone magazine as sounding like "the tubular groaning of a galactic refrigerator" and as displeasing to experience as "a night in a bus terminal".[22] In the 1979 Rolling Stone Record Guide, critic Billy Altman said it was "a two-disc set consisting of nothing more than ear-wrecking electronic sludge, guaranteed to clear any room of humans in record time". (This aspect of the album is mentioned in the Bruce Sterling short story "Dori Bangs".) The first issue of the seminal New York zine Punk placed Reed and the album in its inaugural 1976 issue, presaging the advent of both punk and the discordance of the New York No Wave scene. Reed biographer Victor Bockris wrote that the recording can be understood as "the ultimate conceptual punk album and the progenitor of New York punk rock". The album was ranked number two in the 1991 book The Worst Rock 'n' Roll Records of All Time by Jimmy Guterman and Owen O'Donnell.[23]

Village Voice critic Robert Christgau referred to Metal Machine Music as Reed's "answer to Environments" and said it had "certainly raised consciousness in both the journalistic and business communities" and was not "totally unlistenable", though he admitted for white noise he would rather listen to "Sister Ray".[13] Writing in MusicHound Rock (1999), Greg Kot gave the album a "woof!" rating (signifying "dog-food"), and opined: "The spin cycle of a washing machine has more melodic variation than the electronic drone that was Metal Machine Music."[16] In 2005, Q magazine included the album in a list of "Ten Terrible Records by Great Artists", and it ranked number four in Q's list of the 50 worst albums of all time. It was again featured in Q in December 2010, on the magazine's "Top Ten Career Suicides" list, where it came eighth overall. The Trouser Press Record Guide referred to it as "four sides of unlistenable oscillator noise", parenthetically calling that assessment "a description, not a value judgment".[24] Mark Deming's review for AllMusic said that while noise rock groups "have created some sort of context for it", Metal Machine Music "hasn't gotten any more user friendly with time", given it "paus[ed] only for side breaks with no rhythms, melodies, or formal structures to buffer the onslaught".[11]

Rock critic Lester Bangs wrote of Metal Machine Music: "as classical music it adds nothing to a genre that may well be depleted. As rock 'n' roll it's interesting garage electronic rock 'n' roll. As a statement it's great, as a giant FUCK YOU it shows integrity—a sick, twisted, dunced-out, malevolent, perverted, psychopathic integrity, but integrity nevertheless." Bangs later wrote a tongue-in-cheek article about the album, titled "The Greatest Album Ever Made", in which he judged it "the greatest record ever made in the history of the human eardrum".[25] In 1998, The Wire included Metal Machine Music in its list of "100 Records That Set the World on Fire (While No One Was Listening)", with Brian Duguid writing:

Q magazine featured Metal Machine Music in its 50 Worst Records of All Time ... What higher recommendation could you possibly need? ... [Metal Machine Music] is at once the pre-eminent deranged noise record, an impossibly cacophonous screech of electric torment, and also a classic of Minimalism; some of the most enigmatic, exquisite harmonies ever documented. It's a pity the CD reissues can't include the original double LP's locked groove, but even if it doesn't last forever, the music is infinitely convoluted. It still awaits a proper critical reappraisal—even the gleefully enthusiastic Lester Bangs didn't fully 'get' Metal Machine Music.[26]

In a December 2017 review, Mark Richardson of Pitchfork gave Metal Machine Music a score of 8.7 out of 10. He describes the album as an "exhilarating" listen.[17]

Despite the intense criticism (or perhaps because of the exposure it generated), Metal Machine Music reportedly sold 100,000 copies in the US, according to the liner notes of the Buddah Records CD issue. The original edition was withdrawn within three weeks of its release.[27]

Performance

[edit]Lou Reed did not perform Metal Machine Music on stage until March 2002, when he collaborated with an avant-garde classical ensemble at the MaerzMusik festival in Berlin. The 10-member group Zeitkratzer performed the original album with Reed in a new arrangement by Ulrich Krieger, featuring classical string, wind, piano, and accordion.[28] Live recordings with (2007) and without (2014; all-acoustic) Reed are available commercially.[29]

A few years later, Reed formed a band named Metal Machine Trio as a noise rock/experimental side project.

In popular culture

[edit]The language of the Star Trek aliens known as the Breen was inspired by Metal Machine Music, which the post-production sound staff were instructed to listen to when creating the electronic cackle that served as the Breen's voices.[30]

On Mystery Science Theater 3000, Joel Hodgson's character likened watching Mighty Jack to "listening to two hours of Lou Reed's Metal Machine Music."

Later on Mystery Science Theater 3000 Michael J. Nelson's character says "Monster gets up and immediately puts on his Metal Machine Music" due to the background music during the mutation scene in The Horror of Party Beach.

Track listing

[edit]Side one

- "Metal Machine Music A-1" – 16:10

Side two

- "Metal Machine Music A-2" – 15:53

Side three

- "Metal Machine Music A-3" – 16:13

Side four

- "Metal Machine Music A-4" – 15:55

On the original vinyl release, timings for sides 1–3 were stated as "16:01", while the 4th side read "16:01 or ∞", as the last groove on the LP was a continuous loop, known as the locked groove. On CD, this locked groove was imitated for the final 2:22 of the track, fading out at the end. On later CD, DVD, and BluRay reissues, the tracks are retitled as "Part 1", "Part 2", "Part 3", and "Part 4."

References

[edit]- Bangs, Lester (1987). "How to Succeed in Torture Without Really Trying". In Greil Marcus (ed.). Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-394-53896-X.

- Fricke, David (2000). Liner notes. Metal Machine Music by Lou Reed, 1975. Buddah Records 74465 99752 2 (reissue).

- Guterman, Jimmy and Owen O'Donnell (1991). The Worst Rock 'n' Roll Records of All Time. New York: Citadel Press.

- Eno, Brian (1996). A Year with Swollen Appendices. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-17995-9.

Citations

[edit]- ^ Alan Licht, Common Tones: Selected Interviews with Artists and Musicians 1995-2020, Blank Forms Edition, Interview with Lou Reed, p. 163

- ^ Alan Licht, Common Tones: Selected Interviews with Artists and Musicians 1995-2020, Blank Forms Edition, Interview with Lou Reed, p. 163

- ^ Alan Licht, Common Tones: Selected Interviews with Artists and Musicians 1995-2020, Blank Forms Edition, Interview with Lou Reed, p. 164

- ^ "Lou Reed is back with experimental music of 1970s". Reuters. April 20, 2010. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- ^ Rowe, Matt (June 8, 2011). "Lou Reed Reissues Newly Remastered Metal Machine Music". The Morton Report. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- ^ Alan Licht, Common Tones: Selected Interviews with Artists and Musicians 1995-2020, Blank Forms Edition, Interview with Lou Reed, pp.170

- ^ Alan Licht, Common Tones: Selected Interviews with Artists and Musicians 1995-2020, Blank Forms Edition, Interview with Lou Reed, pp.170

- ^ "Blue" Gene Tyranny on Lou Reed Metal Machine Music

- ^ The album listed (misspelling included) "Drone cognizance and harmonic possibilities vis a vis Lamont Young's Dream Music" among its "Specifications": text copy, image copy (reissue).

- ^ "Pitchfork: Interviews: Lou Reed". Pitchforkmedia.com. Archived from the original on January 13, 2009. Retrieved August 2, 2010.

- ^ a b Deming, Mark. Lou Reed Metal Machine Music. AllMusic. Retrieved July 14, 2022.

- ^ Kot, Greg (January 12, 1992). "Guide to Lou Reed's recordings". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved March 4, 2015.

- ^ a b Christgau, Robert (1981). "Consumer Guide '70s: R". Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies. Ticknor & Fields. ISBN 089919026X. Retrieved March 10, 2019 – via robertchristgau.com.

- ^ Fortnam, Ian (June 2010). "Lou Reed Metal Machine Music". Classic Rock. p. 93.

- ^ DF (August 2, 1975). "Lou Reed" (PDF). Disc. p. 21. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 31, 2023.

- ^ a b Gary Graff & Daniel Durchholz (eds), MusicHound Rock: The Essential Album Guide, Visible Ink Press (Farmington Hills, MI, 1999; ISBN 1-57859-061-2), p. 931.

- ^ a b Richardson, Mark (December 3, 2017). "Lou Reed: Metal Machine Music". Pitchfork. Retrieved December 4, 2017.

- ^ Draper, Jason (June 2010). "Lou Reed – Metal Machine Music". Record Collector. Retrieved July 27, 2017.

- ^ DeCurtis, Anthony; Henke, James; George-Warren, Holly, eds. (1992). The Rolling Stone Album Guide (3rd ed.). Random House. p. 582. ISBN 0679737294.

- ^ Hull, Tom (November 13, 2023). "Grade List: Lou Reed". Tom Hull – on the Web. Retrieved November 13, 2023.

- ^ Segal, Dave (2015). "Two of the Most Divisive LPs of All Time—Miles Davis's Agharta and Lou Reed's Metal Machine Music—Are Now 40 Years Old". The Stranger. Seattle. Archived from the original on May 16, 2016. Retrieved May 15, 2016.

- ^ Wolcott, James. Rolling Stone Review. August 14, 1975.

- ^ "Rocklist.net...Steve Parker...Slipped Discs". Rocklistmusic.co.uk. Retrieved August 2, 2010.

- ^ "Lou Reed". TrouserPress.com. Retrieved August 2, 2010.

- ^ Bangs, Lester. "The Greatest Album Ever Made". Creem, March 1976

- ^ Duguid, Brian (September 1998). "100 Records That Set the World on Fire (While No One Was Listening) — Lou Reed Metal Machine Music (RCA 1975, Reissued Great Expectations 1991)". The Wire. No. 175. London. p. 36 – via Exact Editions.

- ^ "BBC - Music - Review of Lou Reed - Metal Machine Music: Re-mastered".

- ^ James, Colin (October 11, 2005). "Lou Reed's 'Metal Machine Music' gets live treatment in Berlin". AP Worldstream. AP. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved November 4, 2012.

- ^ Richardson, Mark. "Zeitkratzer: Metal Machine Music". Pitchfork. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- ^ Terry J. Erdmann; Paula M. Block (2000). Deep Space Nine Companion. Simon and Schuster. pp. 702–703. ISBN 978-0-671-50106-8.

Further reading

[edit]- Morley, Paul. "Metal Machine Music". Words and Music: A History of Pop in the Shape of a City. London: Bloomsbury, 2003. ISBN 0-7475-5778-0

See also

[edit]- Arc, a Neil Young and Crazy Horse live album featuring an edited composition consisting of only feedback.