Fry's Electronics

| |

| Company type | Private |

|---|---|

| Industry | Retail |

| Founded | May 17, 1985 Sunnyvale, California, U.S. |

| Founders | John Fry Randy Fry David Fry |

| Defunct | February 24, 2021 |

| Fate | Liquidation; general assignment, cited reasons were the COVID-19 pandemic and a "difficult, ever-changing retail environment" |

| Headquarters | , U.S. |

Number of locations | 30 (at the time of closure)[a] |

Area served | United States (locations in Arizona, California, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Nevada, Oregon, Texas and Washington) |

Key people | John Fry, CEO Randy Fry, President David Fry, CFO / CIO Kathryn Kolder, Executive Vice President |

| Products | Consumer electronics retail |

| Revenue | |

Number of employees | 14,000 (2018)[2] |

| Website | Archived official website at the Wayback Machine (archive index) |

Fry's Electronics was an American big-box store chain. It was headquartered in San Jose, California, in Silicon Valley. Fry's retailed software, consumer electronics, household appliances, cosmetics, tools, toys, accessories, magazines, technical books, snack foods, electronic components, and computer hardware. Fry's had in-store computer repair and custom computer building services.

Fry's began with one store in Sunnyvale, California, and expanded to 34 stores in nine states at its peak in 2019.[1][2]

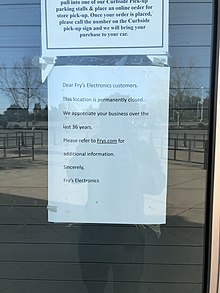

On February 24, 2021, Fry's announced the immediate and permanent closure of all of its stores. A statement posted on its website cited "changes in the retail industry and the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic".[3][4][5]

History

[edit]

In 1972, Charles Fry sold the Fry's Supermarkets chain based in California for US$14 million to Dillons.[7] He gave a portion of the proceeds, around $1 million, to each of his sons, John (who had worked as the IT manager for the supermarket chain), W. Randolph (who goes by the nickname "Randy"), and David, none of whom had much interest in grocery store retailing.[8][9] Instead, on May 17, 1985, they joined together with a fourth partner, John's former girlfriend Kathryn Kolder, to open the first Fry's Electronics store at a 20,000 sq ft (1,900 m2) site in Sunnyvale, California.[10] Today, Fry's Food and Drug stores are owned and operated by Kroger, and are not affiliated with Fry's Electronics, although they have similar logos.[11]

John's idea was to use the model of grocery retailing, with which the brothers were familiar, to sell computer and electronics supplies.[12] The original Sunnyvale store (located near the intersection of Oakmead Parkway and Lakeside Drive[13]) stocked numerous high-tech supplies such as integrated circuits, test and measurement equipment, and computer components, as well as software and various other types of consumer electronics. The store was one of the few retail outlets in the country that sold off-the-shelf microprocessors, such as the Intel 80286. The store also sold T-shirts, technical books, potato chips, and magazines, including Playboy.[9][14] At first, roughly half the store was stocked with groceries, including fresh produce, but the groceries section quickly diminished to displays of soft drinks and snack foods. The store billed itself as "The One-Stop Shop for the Silicon Valley Professional", as one could buy both electronics and groceries (computer chips and potato chips) at the same time.[15] Most components from most OEMs, were available for purchase, to assemble a desktop computer, à la carte.[16]

As the business expanded, the original Sunnyvale store closed, and a newer, larger store was opened across Lawrence Expressway on Kern Avenue. The second Sunnyvale store was designed to look like the interior of a giant computer; the walls were adorned with simulated circuit components, and the floor resembled a giant printed circuit board. The exterior was painted to mimic a huge DIP integrated circuit, and the door handles imitated the ENTER and ESC keys on a computer keyboard; since 2005, this store has housed a Sports Basement store (which still bore some of the door-handle keys until sometime between 2009 and 2013). Fry's moved again to its final Sunnyvale location at 1077 E Arques Ave. at the corner of Arques and Santa Trinita Ave, the former site of a facility of the Link Flight Simulation Division of the Singer Corporation. Each of the three Sunnyvale store locations was located within 1 mile (1.6 km) of the others.[13]

Because Fry's stores were enormous, stocking a wide range of each product category, they were popular with electronics and computer hobbyists and professionals.[17][18] One of the few stores to challenge Fry's in all dimensions (production selection and store-wide themes) was Incredible Universe, a series of Tandy (Radio Shack) superstores, which were established in 1992, bought out, and converted into Fry's in 1996. Historically, Circuit City and CompUSA were major competitors in the computer space, but they collapsed during the late-2000s recession, leaving Micro Center and Newegg as Fry's main competitors.

In August 2014, Fry's Electronics operated 34 brick-and-mortar stores in 9 U.S. states: California (17),[19] Texas (8), Arizona (2), Georgia (2), and one each in Illinois, Indiana, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington.[20]

In August 2019, Fry's announced that it would close its oldest extant location in Palo Alto, by January 2020; the company said its lease at the location would not be renewed.[21] On September 10, 2019, The Mercury News reported that customers were finding barren shelves in most stores, speculating that the chain was about to fold;[22] Fry's responded by stating the company was changing to a consignment model with its vendors and was not planning to close any store other than Palo Alto.[23] However, on January 7, 2020, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution reported that the Fry's location in Duluth, Georgia, was shuttered without advance notice during the 2019 holiday season.[24] On February 25, 2020, Fry's announced that they would close their Anaheim location by March 2, 2020.[25] On November 10, 2020, Fry's closed its Campbell location permanently without notice.

Closure

[edit]On the evening of February 23, 2021, several internet sources began claiming employees were given notice that all remaining stores would close to the public nationwide, with the Frys.com website scheduled to go offline at 12:00 am PST. The company deleted its Facebook page, and set the company Twitter account to protected, hiding all activity.[26] Bay Area broadcaster KRON-TV confirmed the closure later that evening.[5]

The Fry's website closed in the early hours of February 24, only showing a letter informing of its closure. According to the letter, the company would implement the shutdown through an orderly wind-down process that it believed would be in the best interests of the company, its creditors, and other stakeholders to maximize the value of the company's assets for its creditors and other stakeholders.[4] The company said those waiting for repairs will be notified how to claim their equipment.[27]

Fry's officially entered General assignment on April 2, 2021, and began to liquidate all remaining assets, including owned real estate with Hilco Global.[28]

Criticism

[edit]In 1997, Forbes reported on a series of issues about Fry's customer service and unorthodox business practices. Among the allegations was that the company had an internal policy, identified as "the double H" or "hoops and hurdles", to delay or prevent customers from obtaining refunds.[9]

In 1998, USA Today and Wired reported that many customers had become frustrated with poor customer service at Fry's stores.[29][30][31][32]

In 2003, actors Denzel Washington, Bruce Willis, and California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger sued Fry's for $10 million each for posting their images on television sets on their print ads and flyers without permission.[33][34]

On Black Friday 2007, customers at the Renton, Washington location complained that Fry's employees were offering to let people cut in front of a long line for a fee. After complaints in the media, Fry's management offered anyone who paid the fee their money back.[35]

In 2008, the Federal Communications Commission found Fry's failed to place the required "analog-only tuner" consumer-alert label on analog televisions, fining them $384,000 (~$533,663 in 2023).[36]

In 2008, Fry's vice president of merchandising and operations, Ausaf Umar Siddiqui, was charged by federal prosecutors in a kickback scheme involving Fry's vendors, fueling sales with mail-in rebates.[37][38][39][40] The alleged scheme was designed to defraud the company. Siddiqui used the funds to (among other things) feed his gambling habit in Las Vegas, where he lost about $162 million.[41]

In September 2012, Fry's Electronics agreed to pay $2.3 million (~$3.02 million in 2023), and to implement preventive measures, to settle a sexual harassment and retaliation[42] lawsuit brought by the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. The settlement was in relation to allegations that an assistant store manager at the Renton store harassed a 20-year-old sales associate by frequently sending her sexually charged text messages and inviting her to his house to drink. After her direct supervisor reported the harassment to Fry's legal department, the company allegedly fired the female salesperson and fired her supervisor for standing up for her.[43]

In 2017, a store in Webster Texas made headlines when a manager set up a display to demonstrate indoor grow lights for sale and used realistic looking but ultimately fake marijuana plants. This was considered unacceptable by the local community considering marijuana was illegal in the state of Texas.

In 2019, rumors about the chain folding spread rapidly, mainly because shelves were empty for long periods of time and stores seemed to emphasize makeup and fragrances over electronics. Fry's responded by stating they were simply switching to a consignment model, not closing down entirely.[23] From when Fry's put out this statement until early 2021, four additional stores closed (three were in California, and one in Duluth, Georgia),[24] which further led many to believe that the company would soon go out of business.

Online sales operation

[edit]Fry's Electronics was late in establishing an online sales presence. They began offering low-cost Internet access in 2000 through their original Web address "Frys.com".[44] The company later bought e-commerce site Cyberian Outpost in November 2001, and started online sales with a different URL (Outpost.com),[45] which confused customers who did not associate the online name with the brick-and-mortar store.[46] For a time in the mid-2000s, the Web site identified itself as "Fry's Electronics Outpost.com", using dual branding in an attempt to create a connection in visitors' minds.[47] In October 2006, a grand reopening of Frys.com introduced the online store with the same name as the retail outlets.[48][49] The outpost.com URL later began redirecting to the Fry's online store.

Domain name acquisitions

[edit]In 1997, David Peter (or David Peter Burlini), who manufactured and sold French fry vending machines under the business name Frenchy Frys, owned the domain name frys.com, and was also involved in another dispute over the domain newricochet.com with Ricochet Networks.[50] David Burlini attended Santa Clara University around the same time that the Fry Brothers were attending.[51][52] Fry's Electronics brought suit against him that year, alleging trademark infringement, and ultimately prevailed in a default judgment.[53][54]

Fry's Electronics aggressively tried to defend its trademark and domain names. In 2001, it threatened to sue Garret Maki[55][56] for scanning and posting the company's print ads on the Web using the domain frysad.com.[57][58] In 2007, Fry's Electronics lost a domain dispute against Prophet Partners Inc., an online advertising company with thousands of generic and descriptive domain names. The arbitrator dismissed the complaint, which requested transfer of the Frys.us domain, ruling that Fry's Electronics did not have any more right to use the "Fry's" mark than other entities with a similar surname or commercial use of the word.[59]

Store themes

[edit]Various Fry's locations were decorated in elaborate themes. For example, the Burbank store, which opened in 1995, carried a theme of 1950s and 1970s science-fiction movies, and featured huge statues of popular characters such as the robot Gort from The Day the Earth Stood Still and Darth Vader from the Star Wars movie series. In addition, giant ants (from the movie Them!) hung from the ceiling, and the bodies of 1957 Chevys and Buicks served as dining tables in the cafe. A flying saucer protruded above the entrance.[citation needed]

Since Fry's acquired seven stores from the Incredible Universe chain of stores, the company had reduced the elaborateness of its themes. With the opening of the store in Fishers, Indiana, Fry's made a "race track" theme with various hanging displays, including "stop" and "go" signs, as well as many photos of what life looked like in the late 1800s and early 1900s in Indianapolis.[citation needed]

Of the chain's 34 stores, 30 of them closed on February 24, 2021. Four stores were closed earlier:

- The Duluth location closed on December 3, 2019.

- The Palo Alto location closed on December 27, 2019.[60]

- The Anaheim location closed on March 2, 2020.

- The Campbell location closed on November 10, 2020.

In media

[edit]Fry's Electronics is prominently featured in the 2022 film Nope, which filmed at the Burbank location following its closure.[61]

The Phoenix, Arizona location is also featured in Season 2, Episode 12 of Mr. Robot.[62]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Fry's Electronics Store Locations". February 24, 2021. Archived from the original on April 15, 2019. Retrieved May 12, 2022.

- ^ a b c "#205 Fry's Electronics". Forbes. 2019. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- ^ Avalos, George; Baron, Ethan (February 24, 2021). "Fry's Electronics goes out of business permanently, closes all stores". The Mercury News. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

- ^ a b "Computer Parts & Accessories, Software, Games, TVs, Cameras". Fry's Electronics. Frys.com. February 24, 2021. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved February 24, 2021.

- ^ a b "Fry's Electronics permanently closes nationwide". KRON4 News. Nexstar Inc. Retrieved February 24, 2021.

- ^ Sheyner, Gennady. "Fry's Electronics to shutter Palo Alto store in January". www.paloaltoonline.com. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

The store's lease for the century-old building at 340 Portage Ave. that once served as a cannery is set to expire on Jan. 31.

- ^ "Dillon Companies Agrees to Buy Food Store Chain". Lawrence Journal-World. May 26, 1972. Retrieved June 5, 2018.

- ^ Harris, Pat Lopes (January 14, 2000). "Fry's mystique: timing, focus, frugality—and lots of advertising", San Jose Business Journal 17, no. 39: p. 52.

- ^ a b c Marsh, Ann; Woolley, Scott (November 3, 1997). "The customer is always right? Not at Fry's". Forbes. Archived from the original on November 9, 1999. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

Showbiz aside, it was serious one-stop shopping with the best prices and selection in town.

- ^ "Corporation Search: Fry's Electronics". California Business Portal. California Secretary of State. 2009. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved March 17, 2009.

- ^ "Grocery Retail". The Kroger Co. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

- ^ "History of Fry's Electronics, Inc". Funding Universe. Retrieved June 5, 2018.

- ^ a b "541 Lakeside Dr, to 1177 Kern Ave, to 1077 E Arques Ave". google. maps. Retrieved February 24, 2021.

- ^ Hoover's Handbook of Private Companies 2005. Hoover's Incorporated. 2005. p. 200. ISBN 9781573111027.

The geek-gaws range from silicon chip to potato chips, from BYTE to Playboy, and high-speed PCs

- ^ Rosenberg, Richard S. (2013). The Social Impact of Computers. Elsevier. p. 2. ISBN 9781483267159.

- ^ Kozinski, Alex. "Plug'n'Pray." (1996) Forbes.

- ^ Siderskiy, Valentin, A. Mohammed, and Vikram Kapila. "Chua's circuit for experimenters using readily available parts from a hobby electronics store." 122nd ASEE Annual Conf. & Exposition. Seattle: American Society for Engineering Education. 2015.

- ^ LaPlante, Alice (February 25, 1991). "Choices". InfoWorld. InfoWorld Media Group, Inc. Retrieved February 24, 2021.

- ^ Nidever, Seth (February 2013). "Fry's Electronics putting warehouse in Hanford" (February 1, 2013). Hanford Sentinel. Retrieved February 24, 2021.

- ^ "Company History". Fry's Electronics. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021.

- ^ Angst, Maggie (August 29, 2019). "Fry's to close its Palo Alto doors for good in January". The Mercury News. San Jose. Retrieved September 21, 2019.

- ^ Squires, Rob (August 19, 2019). "Fry's Electronics stores soon to close, seeing same fate as Toys'R'Us?". TweakTown. Retrieved February 24, 2021.

- ^ a b Sumagaysay, Levi (September 10, 2019). "Fry's tries to quell rumors of its demise as customers worry about empty shelves". The Mercury News. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- ^ a b Coyne, Amanda C. (January 7, 2020). "Fry's Electronics near Gwinnett Place Mall has closed". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved January 8, 2020.

- ^ Smith, Kevin (February 25, 2020). "Fry's Electronics in Anaheim to close March 2". The Orange County Register. Anaheim.

- ^ Machkovech, Sam (February 24, 2021). "Report: Fry's Electronics going out of business, shutting down all stores". Ars Technica. Conde Nast. Retrieved February 24, 2021.

- ^ "The remaining Fry's Electronics stores are all shutting down". finance.yahoo.com. February 24, 2021. Retrieved February 27, 2021.

- ^ "Assignment for the Benefit of Creditors". proofofclaims.com. Retrieved June 17, 2021.

- ^ Schmit, Julie (February 11, 1998). "Techies flock to Fry's despite its flaws". USA Today. p. 1B.

- ^ "Customer disservice". salon 21st. Archived from the original on August 19, 1999.

- ^ "Customer disservice 2". Salon 21st. February 29, 2000. Archived from the original on February 29, 2000.

- ^ Parks, B. "The Future of Retail: Fry's Electronics-part Disney, part S/M dungeon." WIRED-SAN FRANCISCO- 6 (1998): 146-146.

- ^ "Arnold, Bruce, Denzel Sue Fry's". ExtremeTech. June 20, 2003. Retrieved March 17, 2009.

- ^ Silverman, Stephen M. (April 10, 2003). "Arnold, Bruce and Denzel Take Action". People. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

- ^ Choi, Bernard (November 23, 2007). "Fry's Shoppers Offered Chance to Cut in Line - For a Price". KING 5 News. Archived from the original on October 7, 2008. Retrieved March 17, 2009.

- ^ "File Number EB-07-SE-204 - NOTICE OF APPARENT LIABILITY FOR FORFEITURE". Federal Communications Commission. April 10, 2008.

- ^ Gerstner, Eitan; Hess, James D. (May 1991). "Who benefits from large rebates: Manufacturer, retailer or consumer?". Economics Letters. 36 (1): 5–8. doi:10.1016/0165-1765(91)90046-N. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

- ^ Chen, Xin; Li, Chung-Lun; Rhee, Byong-Duk; Simchi-Levi, David (September 2007). "The impact of manufacturer rebates on supply chain profits" (PDF). Naval Research Logistics. 54 (6): 667–680. doi:10.1002/nav.20239. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

- ^ site:images.frys.com/art/rebates_pdf/

- ^ RD McKenzie (2008). "The Economics of Manufacturers' Rebates". Why Popcorn Costs So Much at the Movies. New York, NY: Springer. pp. 195–209. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-77001-7_10. ISBN 978-0-387-76999-8. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

- ^ Robertson, Jordan (January 8, 2009). "Feds indict former Fry's exec accused of embezzling". Daily Breeze. Torrence, Calif. Archived from the original on January 11, 2009. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- ^ "Fry's Electronics to pay $2.3 million in sexual harassment case". Los Angeles Times. August 31, 2012. Retrieved February 24, 2021.

- ^ "Fry's Electronics Pays $2.3 Million to Settle EEOC Sexual Harassment and Retaliation Lawsuit". The National Law Review. U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. September 2, 2012. Retrieved October 13, 2012.

- ^ "Welcome to Fry's.com". Fry's Electronics. Archived from the original on October 18, 2000. Retrieved March 17, 2009.

- ^ "Welcome to Fry's Outpost.com". Cyberian Outpost, Inc. Archived from the original on September 14, 2002. Retrieved March 17, 2009.

- ^ Del Conte, Natali T. (October 27, 2006). "Fry's Electronics (Finally) Launches Online Store". ExtremeTech. Ziff Davis Publishing. Retrieved March 17, 2009.

- ^ For example, see this archived version of the site home page from 2005

- ^ Sandoval, Greg; Jeff Pelline (February 18, 2000). "Fry's may launch ISP as part of new Net strategy". CNET News. Retrieved March 17, 2009.

- ^ Quinn, Michelle (October 21, 2006). "Fry's Electronics steps up Web presence". San Jose Mercury News. Archived from the original on November 6, 2006. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

- ^ Ricochet Networks, Inc. v. David Peter, a/k/a David Peter Burlini, Newricochet.net and Ricochet Users Association, D2002 WIPO 01686 (June 4, 2002).

- ^ "Santa Clara University, Santa Clara, California". Classmates.com. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

- ^ "Business and Engineering - Notable Alumni". Santa Clara University. Retrieved July 9, 2018.

- ^ Zimmerman, Mitchell (1998). "Securing and Protecting a Domain Name for your Web Site" (PDF). Fenwick & West LLP. Retrieved March 17, 2009.

- ^ Harper, Will (August 19, 1999). "Invasion of the Domain Snatchers". Metroactive. Retrieved March 17, 2009.

- ^ Maki, Garret; Ordoñez, Rodrigo (November 1, 2007). "Installation Profile: Legislative Sound". Sound & Video Contractor. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

Inside the U.S. Senate Chamber's digital audio upgrade.

- ^ "Sunset Digital Masters 'Sullivan Show'". Creative Planet Network. February 14, 2012. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

Sunset Digital is a creative and technical film and video postproduction company specializing in a variety of media and data, and servicing every aspect of the entertainment industry. Garret Maki, VP, New Media for Sunset Digital, supervises the company's DVD division.

- ^ "Fry's Electronics Current Newspaper Ad Online". FrysAd.com. April 7, 2000. Archived from the original on April 7, 2000. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

- ^ Sandoval, Greg (February 23, 2001). "Fry's accuses site owner of cybersquatting". CNET News. Retrieved March 17, 2009.

- ^ Bauer, Esq., Steven M. (February 15, 2007). "Reward of Arbitrator: Fry's Electronics and Prophet Partners" (PDF). American Arbitration Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 17, 2008. Retrieved March 17, 2009.

- ^ Sheyner, Gennady (December 27, 2019). "The era of Fry's Electronics comes to an end in Palo Alto". paloaltoonline.com. Retrieved February 24, 2021.

- ^ SFGATE, Amanda Bartlett (July 27, 2022). "How Jordan Peele brought Fry's Electronics back to life in 'Nope'". SFGATE. Retrieved August 1, 2022.

- ^ "Mr. Robot at Fry's Electronics - filming location". www.sceen-it.com. Retrieved August 10, 2022.

Notes

[edit]External links

[edit]- Last snapshot of official website prior to closing on February 25, 2021

- "Computer Parts & Accessories, Software, Games, TVs, Cameras". Fry's Electronics. Frys.com. February 24, 2021. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved February 24, 2021.

- "Weekly Newspaper Ads". Fry's Electronics. March 22, 2019. Archived from the original on March 22, 2019. Retrieved February 24, 2021.

- "Company History". Fry's Electronics. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021.

- "Discussions". Fry's Forum.

Fry's Forum is not affiliated with Fry's Electronics, Inc.

- 1985 establishments in California

- 2021 disestablishments in California

- American companies established in 1985

- American companies disestablished in 2021

- Companies based in San Jose, California

- Defunct consumer electronics retailers in the United States

- Privately held companies based in California

- Retail companies established in 1985

- Companies disestablished due to the COVID-19 pandemic

- Retail companies disestablished in 2021