Phonograph record

A phonograph record (also known as a gramophone record, especially in British English) or a vinyl record (for later varieties only) is an analog sound storage medium in the form of a flat disc with an inscribed, modulated spiral groove. The groove usually starts near the outside edge and ends near the center of the disc. The stored sound information is made audible by playing the record on a phonograph (or "gramophone", "turntable", or "record player").

Records have been produced in different formats with playing times ranging from a few minutes to around 30 minutes per side. For about half a century, the discs were commonly made from shellac and these records typically ran at a rotational speed of 78 rpm, giving it the nickname "78s" ("seventy-eights"). After the 1940s, "vinyl" records made from polyvinyl chloride (PVC) became standard replacing the old 78s and remain so to this day; they have since been produced in various sizes and speeds, most commonly 7-inch discs played at 45 rpm (typically for singles, also called 45s ("forty-fives")), and 12-inch discs played at 33⅓ rpm (known as an LP, "long-playing records", typically for full-length albums) – the latter being the most prevalent format today.

Overview

[edit]The phonograph record was the primary medium used for music reproduction throughout the 20th century. It had co-existed with the phonograph cylinder from the late 1880s and had effectively superseded it by around 1912. Records retained the largest market share even when new formats such as the compact cassette were mass-marketed. By the 1980s, digital media, in the form of the compact disc, had gained a larger market share, and the record left the mainstream in 1991.[1] Since the 1990s, records continue to be manufactured and sold on a smaller scale, and during the 1990s and early 2000s were commonly used by disc jockeys (DJs), especially in dance music genres. They were also listened to by a growing number of audiophiles. The phonograph record has made a niche resurgence in the early 21st century,[2][3] growing increasingly popular throughout the 2010s and 2020s.[4]

Phonograph records are generally described by their diameter in inches (12-inch, 10-inch, 7-inch), the rotational speed in revolutions per minute (rpm) at which they are played (8+1⁄3, 16+2⁄3, 33+1⁄3, 45, 78),[5] and their time capacity, determined by their diameter and speed (LP [long play], 12-inch disc, 33+1⁄3 rpm; EP [extended play], 12-inch disc or 7-inch disc, 33+1⁄3 or 45 rpm; Single, 7-inch or 10-inch disc, 45 or 78 rpm); their reproductive quality, or level of fidelity (high-fidelity, orthophonic, full-range, etc.); and the number of audio channels (mono, stereo, quad, etc.).[citation needed]

The phrase broken record refers to a malfunction when the needle skips/jumps back to the previous groove and plays the same section over and over again indefinitely.[6][7]

Naming

[edit]The various names have included phonograph record (American English), gramophone record (British English), record, vinyl, LP (originally a trademark of Columbia Records), black disc,[8] album, and more informally platter,[9] wax,[10] or liquorice pizza.[11]

Early development

[edit]Manufacture of disc records began in the late 19th century, at first competing with earlier cylinder records. Price, ease of use and storage made the disc record dominant by the 1910s. The standard format of disc records became known to later generations as "78s" after their playback speed in revolutions per minute, although that speed only became standardized in the late 1920s. In the late 1940s new formats pressed in vinyl, the 45 rpm single and 33 rpm long playing "LP", were introduced, gradually overtaking the formerly standard "78s" over the next decade. The late 1950s saw the introduction of stereophonic sound on commercial discs.

Predecessors

[edit]The phonautograph was invented by 1857 by Frenchman Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville.[12] It could not, however, play back recorded sound,[13] as Scott intended for people to read back the tracings,[14] which he called phonautograms.[15] Prior to this, tuning forks had been used in this way to create direct tracings of the vibrations of sound-producing objects, as by English physicist Thomas Young in 1807.[16]

In 1877, Thomas Edison invented the first phonograph,[17] which etched sound recordings onto phonograph cylinders. Unlike the phonautograph, Edison's phonograph could both record and reproduce sound, via two separate needles, one for each function.[18]

The first disc records

[edit]

The first commercially sold disc records were created by Emile Berliner in the 1880s. Emile Berliner improved the quality of recordings while his manufacturing associate Eldridge R. Johnson, who owned a machine shop in Camden, New Jersey, eventually improved the mechanism of the gramophone with a spring motor and a speed regulating governor, resulting in a sound quality equal to Edison's cylinders. Abandoning Berliner's "Gramophone" trademark for legal reasons in the United States, Johnson's and Berliner's separate companies reorganized in 1901 to form the Victor Talking Machine Company in Camden, New Jersey, whose products would come to dominate the market for several decades.[19]

Berliner's Montreal factory, which became the Canadian branch of RCA Victor, still exists. There is a dedicated museum in Montreal for Berliner (Musée des ondes Emile Berliner).[20]

78 rpm disc developments

[edit]Early speeds

[edit]

Early disc recordings were produced in a variety of speeds ranging from 60 to 130 rpm, and a variety of sizes. As early as 1894, Emile Berliner's United States Gramophone Company was selling single-sided 7-inch discs with an advertised standard speed of "about 70 rpm".[21]

One standard audio recording handbook describes speed regulators, or governors, as being part of a wave of improvement introduced rapidly after 1897. A picture of a hand-cranked 1898 Berliner Gramophone shows a governor and says that spring drives had replaced hand drives. It notes that:

The speed regulator was furnished with an indicator that showed the speed when the machine was running so that the records, on reproduction, could be revolved at exactly the same speed...The literature does not disclose why 78 rpm was chosen for the phonograph industry, apparently this just happened to be the speed created by one of the early machines and, for no other reason continued to be used.[22]

In 1912, the Gramophone Company set 78 rpm as their recording standard, based on the average of recordings they had been releasing at the time, and started selling players whose governors had a nominal speed of 78 rpm.[23] By 1925, 78 rpm was becoming standardized across the industry. However, the exact speed differed between places with alternating current electricity supply at 60 hertz (cycles per second, Hz) and those at 50 Hz. Where the mains supply was 60 Hz, the actual speed was 78.26 rpm:[24] that of a 60 Hz stroboscope illuminating 92-bar calibration markings. Where it was 50 Hz, it was 77.92 rpm: that of a 50 Hz stroboscope illuminating 77-bar calibration markings.[23]

At least one attempt to lengthen playing time was made in the early 1920s. World Records produced records that played at a constant linear velocity, controlled by Noel Pemberton Billing's patented add-on speed governor.[25]

Acoustic recording

[edit]Early recordings were made entirely acoustically, the sound was collected by a horn and piped to a diaphragm, which vibrated the cutting stylus. Sensitivity and frequency range were poor, and frequency response was irregular, giving acoustic recordings an instantly recognizable tonal quality. A singer almost had to put their face in the recording horn. A way of reducing resonance was to wrap the recording horn with tape.[26]

Even drums, if planned and placed properly, could be effectively recorded and heard on even the earliest jazz and military band recordings. The loudest instruments such as the drums and trumpets were positioned the farthest away from the collecting horn. Lillian Hardin Armstrong, a member of King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band, which recorded at Gennett Records in 1923, remembered that at first Oliver and his young second trumpet, Louis Armstrong, stood next to each other and Oliver's horn could not be heard. "They put Louis about fifteen feet over in the corner, looking all sad."[27][28]

Electrical recording

[edit]

During the first half of the 1920s, engineers at Western Electric, as well as independent inventors such as Orlando Marsh, developed technology for capturing sound with a microphone, amplifying it with vacuum tubes[29] (known as valves in the UK[30]), and then using the amplified signal to drive an electromechanical recording head. Western Electric's innovations resulted in a broader and smoother frequency response, which produced a dramatically fuller, clearer and more natural-sounding recording. Soft or distant sounds that were previously impossible to record could now be captured. Volume was now limited only by the groove spacing on the record and the amplification of the playback device. Victor and Columbia licensed the new electrical system from Western Electric and recorded the first electrical discs during the spring of 1925. The first electrically recorded Victor Red Seal record was Chopin's "Impromptus" and Schubert's "Litanei" performed by pianist Alfred Cortot at Victor's studios in Camden, New Jersey.[29]

A 1926 Wanamaker's ad in The New York Times offers records "by the latest Victor process of electrical recording".[31] It was recognized as a breakthrough; in 1930, a Times music critic stated:

... the time has come for serious musical criticism to take account of performances of great music reproduced by means of the records. To claim that the records have succeeded in exact and complete reproduction of all details of symphonic or operatic performances ... would be extravagant ... [but] the article of today is so far in advance of the old machines as hardly to admit classification under the same name. Electrical recording and reproduction have combined to retain vitality and color in recitals by proxy.[32]

The Orthophonic Victrola had an interior folded exponential horn, a sophisticated design informed by impedance-matching and transmission-line theory, and designed to provide a relatively flat frequency response. Victor's first public demonstration of the Orthophonic Victrola on 6 October 1925, at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel was front-page news in The New York Times, which reported:

The audience broke into applause ... John Philip Sousa [said]: '[Gentlemen], that is a band. This is the first time I have ever heard music with any soul to it produced by a mechanical talking machine' ... The new instrument is a feat of mathematics and physics. It is not the result of innumerable experiments, but was worked out on paper in advance of being built in the laboratory ... The new machine has a range of from 100 to 5,000 [cycles per second], or five and a half octaves ... The 'phonograph tone' is eliminated by the new recording and reproducing process.[34]

Sales of records plummeted precipitously during the early years of the Great Depression of the 1930s, and the entire record industry in America nearly foundered. In 1932, RCA Victor introduced a basic, inexpensive turntable called the Duo Jr., which was designed to be connected to their radio receivers. According to Edward Wallerstein (the general manager of the RCA Victor Division), this device was "instrumental in revitalizing the industry".[35]

78 rpm materials

[edit]The production of shellac records continued throughout the 78 rpm era, which lasted until 1948 in industrialized nations.[36]

During the Second World War, the United States Armed Forces produced thousands of 12-inch vinyl 78 rpm V-Discs for use by the troops overseas.[37] After the war, the use of vinyl became more practical as new record players with lightweight crystal pickups and precision-ground styli made of sapphire or an exotic osmium alloy proliferated. In late 1945, RCA Victor began offering "De Luxe" transparent red vinylite pressings of some Red Seal classical 78s, at a de luxe price. Later, Decca Records introduced vinyl Deccalite 78s, while other record companies used various vinyl formulations trademarked as Metrolite, Merco Plastic, and Sav-o-flex, but these were mainly used to produce "unbreakable" children's records and special thin vinyl DJ pressings for shipment to radio stations.[38]

78 rpm recording time

[edit]The playing time of a phonograph record is directly proportional to the available groove length divided by the turntable speed. Total groove length in turn depends on how closely the grooves are spaced, in addition to the record diameter. At the beginning of the 20th century, the early discs played for two minutes, the same as cylinder records.[39] The 12-inch disc, introduced by Victor in 1903, increased the playing time to three and a half minutes.[40] Because the standard 10-inch 78 rpm record could hold about three minutes of sound per side, most popular recordings were limited to that duration.[41] For example, when King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band, including Louis Armstrong on his first recordings, recorded 13 sides at Gennett Records in Richmond, Indiana, in 1923, one side was 2:09 and four sides were 2:52–2:59.[42]

In January 1938, Milt Gabler started recording for Commodore Records, and to allow for longer continuous performances, he recorded some 12-inch discs. Eddie Condon explained: "Gabler realized that a jam session needs room for development." The first two 12-inch recordings did not take advantage of their capability: "Carnegie Drag" was 3m 15s; "Carnegie Jump", 2m 41s. But at the second session, on 30 April, the two 12-inch recordings were longer: "Embraceable You" was 4m 05s; "Serenade to a Shylock", 4m 32s.[43][44] Another way to overcome the time limitation was to issue a selection extending to both sides of a single record. Vaudeville stars Gallagher and Shean recorded "Mr. Gallagher and Mr. Shean", written by themselves or, allegedly, by Bryan Foy, as two sides of a 10-inch 78 in 1922 for Victor.[45] Longer musical pieces were released as a set of records. In 1903 His Master's Voice in England made the first complete recording of an opera, Verdi's Ernani, on 40 single-sided discs.[46]

In 1940, Commodore released Eddie Condon and his Band's recording of "A Good Man Is Hard to Find" in four parts, issued on both sides of two 12-inch 78s. The limited duration of recordings persisted from their advent until the introduction of the LP record in 1948. In popular music, the time limit of 3+1⁄2 minutes on a 10-inch 78 rpm record meant that singers seldom recorded long pieces. One exception is Frank Sinatra's recording of Rodgers and Hammerstein's "Soliloquy", from Carousel, made on 28 May 1946. Because it ran 7m 57s, longer than both sides of a standard 78 rpm 10-inch record, it was released on Columbia's Masterwork label (the classical division) as two sides of a 12-inch record.[47]

In the 78 era, classical-music and spoken-word items generally were released on the longer 12-inch 78s, about 4–5 minutes per side. For example, on 10 June 1924, four months after the 12 February premier of Rhapsody in Blue, George Gershwin recorded an abridged version of the seventeen-minute work with Paul Whiteman and His Orchestra. It was released on two sides of Victor 55225 and ran for 8m 59s.[48]

Record albums

[edit]"Record albums" were originally booklets containing collections of multiple disc records of related material, the name being related to photograph albums or scrap albums. [49] German record company Odeon pioneered the album in 1909 when it released the Nutcracker Suite by Tchaikovsky on four double-sided discs in a specially designed package.[46] It was not until the LP era that an entire album of material could be included on a single record.

78 rpm releases in the microgroove era

[edit]In 1968, when the hit movie Thoroughly Modern Millie was inspiring revivals of Jazz Age music, Reprise planned to release a series of 78-rpm singles from their artists on their label at the time, called the Reprise Speed Series. Only one disc actually saw release, Randy Newman's "I Think It's Going to Rain Today", a track from his self-titled debut album (with "The Beehive State" on the flipside).[50] Reprise did not proceed further with the series due to a lack of sales for the single, and a lack of general interest in the concept.[51]

In 1978, guitarist and vocalist Leon Redbone released a promotional 78-rpm single featuring two songs ("Alabama Jubilee" and "Please Don't Talk About Me When I'm Gone") from his Champagne Charlie album.[52]

In the same vein of Tin Pan Alley revivals, R. Crumb & His Cheap Suit Serenaders issued a number of 78-rpm singles on their Blue Goose record label. The most familiar of these releases is probably R. Crumb & His Cheap Suit Serenaders' Party Record (1980, issued as a "Red Goose" record on a 12-inch single), with the double-entendre "My Girl's Pussy" on the "A" side and the X-rated "Christopher Columbus" on the "B" side.

In the 1990s Rhino Records issued a series of boxed sets of 78-rpm reissues of early rock and roll hits, intended for owners of vintage jukeboxes. The records were made of vinyl, however, and some of the earlier vintage 78-rpm jukeboxes and record players (the ones that were pre-war) were designed with heavy tone arms to play the hard slate-impregnated shellac records of their time. These vinyl Rhino 78s were softer and would be destroyed by old juke boxes and old record players, but play well on newer 78-capable turntables with modern lightweight tone arms and jewel needles.[53]

As a special release for Record Store Day 2011, Capitol re-released The Beach Boys single "Good Vibrations" in the form of a 10-inch 78-rpm record (b/w "Heroes and Villains"). More recently, The Reverend Peyton's Big Damn Band has released their tribute to blues guitarist Charley Patton Peyton on Patton on both 12-inch LP and 10-inch 78s.[54]

New sizes and materials after WWII

[edit]

CBS Laboratories had long been at work for Columbia Records to develop a phonograph record that would hold at least 20 minutes per side.[55][56]

Research began in 1939, was suspended during World War II, and then resumed in 1945.[57] Columbia Records unveiled the LP at a press conference in the Waldorf-Astoria on 21 June 1948, in two formats: 10 inches (25 centimetres) in diameter, matching that of 78 rpm singles, and 12 inches (30 centimetres) in diameter.[57][58][59]

Unwilling to accept and license Columbia's system, in February 1949, RCA Victor released the first 45 rpm single, 7 inches in diameter with a large center hole. The 45 rpm player included a changing mechanism that allowed multiple disks to be stacked, much as a conventional changer handled 78s. Also like 78s, the short playing time of a single 45 rpm side meant that long works, such as symphonies and operas, had to be released on multiple 45s instead of a single LP, but RCA Victor claimed that the new high-speed changer rendered side breaks so brief as to be inconsequential. Early 45 rpm records were made from either vinyl or polystyrene.[60] They had a playing time of eight minutes.[61]

At first the two systems were marketed in competition, in what was called "The War of the Speeds".[62]

Speeds

[edit]Shellac era

[edit]

The older 78 rpm format continued to be mass-produced alongside the newer formats using new materials in decreasing numbers until the summer of 1958 in the U.S., and in a few countries, such as the Philippines and India (both countries issued recordings by the Beatles on 78s), into the late 1960s. For example, Columbia Records' last reissue of Frank Sinatra songs on 78 rpm records was an album called Young at Heart, issued in November 1954.[64]

Microgroove and vinyl era

[edit]

Columbia and RCA Victor each pursued their R&D secretly.[65]

The commercial rivalry between RCA Victor and Columbia Records led to RCA Victor's introduction of what it had intended to be a competing vinyl format, the 7-inch (175 mm) 45 rpm disc, with a much larger center hole. For a two-year period from 1948 to 1950, record companies and consumers faced uncertainty over which of these formats would ultimately prevail in what was known as the "War of the Speeds" (see also Format war). In 1949 Capitol and Decca adopted the new LP format and RCA Victor gave in and issued its first LP in January 1950. The 45 rpm size was gaining in popularity, too, and Columbia issued its first 45s in February 1951. By 1954, 200 million 45s had been sold.[66]

Eventually the 12-inch (300 mm) 33+1⁄3 rpm LP prevailed as the dominant format for musical albums, and 10-inch LPs were no longer issued. The last Columbia Records reissue of any Frank Sinatra songs on a 10-inch LP record was an album called Hall of Fame, CL 2600, issued on 26 October 1956, containing six songs, one each by Tony Bennett, Rosemary Clooney, Johnnie Ray, Frank Sinatra, Doris Day, and Frankie Laine.[64]

The 45 rpm discs also came in a variety known as extended play (EP), which achieved up to 10–15 minutes play at the expense of attenuating (and possibly compressing) the sound to reduce the width required by the groove. EP discs were cheaper to produce and were used in cases where unit sales were likely to be more limited or to reissue LP albums on the smaller format for those people who had only 45 rpm players. LP albums could be purchased one EP at a time, with four items per EP, or in a boxed set with three EPs or twelve items. The large center hole on 45s allows easier handling by jukebox mechanisms. EPs were generally discontinued by the late 1950s in the U.S. as three- and four-speed record players replaced the individual 45 players. One indication of the decline of the 45 rpm EP is that the last Columbia Records reissue of Frank Sinatra songs on 45 rpm EP records, called Frank Sinatra (Columbia B-2641) was issued on 7 December 1959.[64]

The Seeburg Corporation introduced the Seeburg Background Music System in 1959, using a 16+2⁄3 rpm 9-inch record with 2-inch center hole. Each record held 40 minutes of music per side, recorded at 420 grooves per inch.[67]

From the mid-1950s through the 1960s, in the U.S. the common home record player or "stereo" (after the introduction of stereo recording) would typically have had these features: a three- or four-speed player (78, 45, 33+1⁄3, and sometimes 16+2⁄3 rpm); with changer, a tall spindle that would hold several records and automatically drop a new record on top of the previous one when it had finished playing, a combination cartridge with both 78 and microgroove styli and a way to flip between the two; and some kind of adapter for playing the 45s with their larger center hole. The adapter could be a small solid circle that fit onto the bottom of the spindle (meaning only one 45 could be played at a time) or a larger adapter that fit over the entire spindle, permitting a stack of 45s to be played.[63]

RCA Victor 45s were also adapted to the smaller spindle of an LP player with a plastic snap-in insert known as a "45 rpm adapter".[63] These inserts were commissioned by RCA president David Sarnoff and were invented by Thomas Hutchison.[citation needed]

Capacitance Electronic Discs were videodiscs invented by RCA, based on mechanically tracked ultra-microgrooves (9541 grooves/inch) on a 12-inch conductive vinyl disc.[68]

High fidelity

[edit]The term "high fidelity" was coined in the 1920s by some manufacturers of radio receivers and phonographs to differentiate their better-sounding products claimed as providing "perfect" sound reproduction.[69] The term began to be used by some audio engineers and consumers through the 1930s and 1940s. After 1949 a variety of improvements in recording and playback technologies, especially stereo recordings, which became widely available in 1958, gave a boost to the "hi-fi" classification of products, leading to sales of individual components for the home such as amplifiers, loudspeakers, phonographs, and tape players.[70] High Fidelity and Audio were two magazines that hi-fi consumers and engineers could read for reviews of playback equipment and recordings.

Stereophonic sound

[edit]

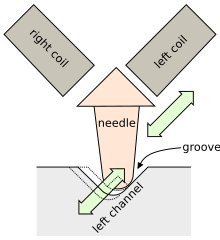

A stereophonic phonograph provides two channels of audio, one left and one right. This is achieved by adding another vertical dimension of movement to the needle in addition to the horizontal one. As a result, the needle now moves not only left and right, but also up and down. But since those two dimensions do not have the same sensitivity to vibration, the difference needs to be evened out by having each channel take half its information from each direction by turning the channels 45 degrees from horizontal.[71]

As a result of the 45-degree turn and some vector addition, it can be demonstrated that out of the new horizontal and vertical directions, one would represent the sum of the two channels, and the other representing the difference. Record makers decide to pick the directions such that the traditional horizontal direction codes for the sum. As a result, an ordinary mono disk is decoded correctly as "no difference between channels", and an ordinary mono player would simply play the sum of a stereophonic record without too much loss of information.[71]

In 1957 the first commercial stereo two-channel records were issued first by Audio Fidelity followed by a translucent blue vinyl on Bel Canto Records, the first of which was a multi-colored-vinyl sampler featuring A Stereo Tour of Los Angeles narrated by Jack Wagner on one side, and a collection of tracks from various Bel Canto albums on the back.[72]

Noise reduction systems

[edit]A similar scheme aiming at the high-end audiophile market, and achieving a noise reduction of about 20 to 25 dB(A), was the Telefunken/Nakamichi High-Com II noise reduction system being adapted to vinyl in 1979. A decoder was commercially available[73] but only one demo record[74] is known to have been produced in this format.

The availability of encoded disks in any of these formats stopped in the mid-1980s.[75]

Yet another noise reduction system for vinyl records was the UC compander system developed by Zentrum Wissenschaft und Technik (ZWT) of Kombinat Rundfunk und Fernsehen (RFT).[76] The system deliberately reduced disk noise by 10 to 12 dB(A) only[77] to remain virtually free of recognizable acoustical artifacts even when records were played back without an UC expander. In fact, the system was undocumented yet introduced into the market by several East-German record labels since 1983.[77][78][79] Over 500 UC-encoded titles were produced[78] without an expander becoming available to the public. The only[79] UC expander was built into a turntable manufactured by Phonotechnik Pirna/Zittau.[80]

Formats

[edit]Types of records

[edit]The usual diameters of the holes on an EP record are 0.286 inches (7.26 mm).[81]

Sizes of records in the United States and the UK are generally measured in inches, e.g. 7-inch records, which are generally 45 rpm records. LPs were 10-inch records at first, but soon the 12-inch size became by far the most common. Generally, 78s were 10-inch, but 12-inch and 7-inch and even smaller were made—the so-called "little wonders".[82]

Standard formats

[edit]

| Diameter | Finished Diameter[A] | Name | Revolutions per minute | Approximate duration (minutes) per side |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 in (41 cm) | 15+15⁄16″ ±3⁄32″ | Transcription disc | 33+1⁄3 | 15 |

| 12 in (30 cm) | 11+7⁄8″ ±1⁄32″ | LP (Long Play) | 33+1⁄3 | 22 |

| Maxi Single, 12-inch single | 45 | 15 | ||

| Single | 78 | 4–5 | ||

| 10 in (25 cm) | 9+7⁄8″ ±1⁄32″ | LP (Long Play) | 33+1⁄3 | 12–15 |

| EP (Extended Play) | 45 | 9–12 | ||

| Single | 78 | 3 | ||

| 7 in (18 cm) | 6+7⁄8″ ±1⁄32″ | EP (Extended Play) | 33+1⁄3[B] | 7 |

| EP (Extended Play) | 45 | 8 | ||

| Single | 45 | 5+1⁄3 |

- Notes:

- ^ Original hole diameters were 0.286″ ±0.001″ for 33+1⁄3 and 78.26 rpm records, and 1.504″ ±0.002″ for 45 rpm records.[83]

- ^ Columbia pressed many 7-inch 33+1⁄3 rpm vinyl singles in 1949, but they were dropped in early 1950 due to the popularity of the RCA Victor 45.[84][full citation needed]

Less common formats

[edit]Flexi discs were thin flexible records that were distributed with magazines and as promotional gifts from the 1960s to the 1980s.

In March 1949, as RCA Victor released the 45, Columbia released several hundred 7-inch, 33+1⁄3 rpm, small-spindle-hole singles. This format was soon dropped as it became clear that the RCA Victor 45 was the single of choice and the Columbia 12-inch LP would be the album of choice.[85] The first release of the 45 came in seven colors: black 47-xxxx popular series, yellow 47-xxxx juvenile series, green (teal) 48-xxxx country series, deep red 49-xxxx classical series, bright red (cerise) 50-xxxx blues/spiritual series, light blue 51-xxxx international series, dark blue 52-xxxx light classics. Most colors were soon dropped in favor of black because of production problems. However, yellow and deep red were continued until about 1952.[86] The first 45 rpm record created for sale was "PeeWee the Piccolo" RCA Victor 47-0147 pressed in yellow translucent vinyl at the Sherman Avenue plant, Indianapolis on 7 December 1948, by R. O. Price, plant manager.[87]

In the 1950s and 1960s Ribs were created within Soviet Union countries as a result of cultural censorship. These black market records were of banned music, printed onto x-ray films scavenged from hospital bins.[88]

In the 1970s, the government of Bhutan produced now-collectible postage stamps on playable vinyl mini-discs.[89]

Recent developments

[edit]In 2018, an Austrian startup, Rebeat Innovation GmBH, received US$4.8 million in funding to develop high definition vinyl records that purport to contain longer play times, louder volumes and higher fidelity than conventional vinyl LPs.[90] Rebeat Innovation, headed by CEO Günter Loibl, has called the format 'HD Vinyl'.[91] The HD process works by converting audio to a digital 3D topography map that is then inscribed onto the vinyl stamper via lasers, resulting in less loss of information. Many critics have expressed skepticism regarding the cost and quality of HD records.[92]

In May 2019, at the Making Vinyl conference in Berlin, Loibl unveiled the software "Perfect Groove" for creating 3D topographic audio data files.[93] The software provides a map for laser-engraving for HD Vinyl stampers. The audio engineering software was created with mastering engineers Scott Hull and Darcy Proper, a four-time Grammy winner. The demonstration offered the first simulations of what HD Vinyl records are likely to sound like, ahead of actual HD vinyl physical record production. Loibl discussed the software "Perfect Groove" at a presentation titled "Vinyl 4.0 The next generation of making records" before offering demonstrations to attendees.[94]

Structure

[edit]

* Some CD-R(W) and DVD-R(W)/DVD+R(W) recorders operate in ZCLV, CAA or CAV modes.

Increasingly from the early 20th century, and almost exclusively since the 1920s, both sides of the record have been used to carry the grooves. Occasional records have been issued since then with a recording on only one side. In the 1980s Columbia records briefly issued a series of less expensive one-sided 45 rpm singles.[95]

Since its inception in 1948, vinyl record standards for the United States follow the guidelines of the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA).[81]

Vinyl quality

[edit]The composition of vinyl used to press records (a blend of polyvinyl chloride and polyvinyl acetate) has varied considerably over the years. Virgin vinyl is preferred, but during the 1970s energy crisis, as a cost-cutting move, much of the industry began reducing the thickness and quality of vinyl used in mass-market manufacturing. Sound quality suffered, with increased ticks, pops, and other surface noises.[96] RCA Records marketed their lightweight LP as Dynaflex, which, at the time, was considered inferior by many record collectors.[97]

It became commonplace to use recycled vinyl. New or "virgin" heavy/heavyweight (180–220 g) vinyl is commonly used for modern audiophile vinyl releases in all genres. Many collectors prefer to have heavyweight vinyl albums, which have been reported to have better sound than normal vinyl because of their higher tolerance against deformation caused by normal play.[98]

Following the vinyl revival of the 21st century, select manufacturers adopted bioplastic-based records due to concerns over the environmental impact of widespread PVC use.[99][100]

Limitations

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2019) |

Shellac

[edit]One problem with shellac was that the size of the disks tended to be larger because it was limited to 80–100 groove walls per inch before the risk of groove collapse became too high, whereas vinyl could have up to 260 groove walls per inch.[101][102]

Vinyl

[edit]Although vinyl records are strong and do not break easily, they scratch due to its soft material sometimes resulting in ruining the record. Vinyl readily acquires a static charge, attracting dust that is difficult to remove completely. Dust and scratches cause audio clicks and pops. In extreme cases, they can cause the needle to skip over a series of grooves, or worse yet, cause the needle to skip backward, creating a "locked groove" that repeats over and over. This is the origin of the phrase "like a broken record" or "like a scratched record", which is often used to describe a person or thing that continually repeats itself.[103]

A further limitation of the gramophone record is that fidelity steadily declines as playback progresses; there is more vinyl per second available for fine reproduction of high frequencies at the large-diameter beginning of the groove than exist at the smaller diameters close to the end of the side. At the start of a groove on an LP there are 510 mm of vinyl per second traveling past the stylus while the ending of the groove gives 200–210 mm of vinyl per second—less than half the linear resolution.[104]

There is controversy about the relative quality of CD sound and LP sound when the latter is heard under the best conditions (see Comparison of analog and digital recording). One technical advantage with vinyl compared to the optical CD is that if correctly handled and stored, the vinyl record can be playable for decades and possibly centuries,[105] which is longer than some versions of the optical CD.[106] For vinyl records to be playable for years to come, they need to be handled with care and stored properly. Guidelines for proper vinyl storage include not stacking records on top of each other, avoiding heat or direct sunlight and placing them in a temperature-controlled area that help prevent vinyl records from warping and scratching. Collectors store their records in a variety of boxes, cubes, shelves and racks.[107]

Sound fidelity

[edit]At the time of the introduction of the compact disc (CD) in 1982, the stereo LP pressed in vinyl continued to suffer from a variety of limitations:

The stereo image was not made up of fully discrete left and right channels; each channel's signal coming out of the cartridge contained a small amount of the signal from the other channel, with more crosstalk at higher frequencies. High-quality disc cutting equipment was capable of making a master disc with 30–40 dB of stereo separation at 1,000 Hz, but the playback cartridges had lesser performance of about 20 to 30 dB of separation at 1000 Hz, with separation decreasing as frequency increased, such that at 12 kHz the separation was about 10–15 dB.[108] A common modern view is that stereo isolation must be higher than this to achieve a proper stereo soundstage. However, in the 1950s the BBC determined in a series of tests that only 20–25 dB is required for the impression of full stereo separation.[109]

Thin, closely spaced spiral grooves that allow for increased playing time on a 33+1⁄3 rpm microgroove LP lead to a tinny pre-echo warning of upcoming loud sounds. The cutting stylus unavoidably transfers some of the subsequent groove wall's impulse signal into the previous groove wall. It is discernible by some listeners throughout certain recordings, but a quiet passage followed by a loud sound allows anyone to hear a faint pre-echo of the loud sound occurring 1.8 seconds ahead of time.[110]

LP versus CD

[edit]Audiophiles have differed over the relative merits of the LP versus the CD since the digital disc was introduced.[111] Digital sampling can theoretically completely reproduce a sound wave within a given range of frequencies if the sampling rate is high enough.[112] Vinyl's drawbacks, however, include surface noise, less resolution due to a lower dynamic range, and greater sensitivity to handling.[113] Modern anti-aliasing filters and oversampling systems used in digital recordings have eliminated perceived problems observed with early CD players.[114]

There is a theory that vinyl records can audibly represent higher frequencies than compact discs, though most of this is noise and not relevant to human hearing. According to Red Book specifications, the compact disc has a frequency response of 20 Hz up to 22,050 Hz, and most CD players measure flat within a fraction of a decibel from at least 0 Hz to 20 kHz at full output. Due to the distance required between grooves, it is not possible for an LP to reproduce as low frequencies as a CD. Additionally, turntable rumble and acoustic feedback obscures the low-end limit of vinyl but the upper end can be, with some cartridges, reasonably flat within a few decibels to 30 kHz, with gentle roll-off. Carrier signals of Quad LPs popular in the 1970s were at 30 kHz to be out of the range of human hearing. The average human auditory system is sensitive to frequencies from 20 Hz to a maximum of around 20,000 Hz.[115] The upper and lower frequency limits of human hearing vary per person. High frequency sensitivity decreases as a person ages, a process called presbycusis.[116]

Preservation

[edit]

As the playing of gramophone records causes gradual degradation of the recording, they are best preserved by transferring them onto other media and playing the records as rarely as possible. They need to be stored on edge, and do best under environmental conditions that most humans would find comfortable.[117] The longevity and optimal performance of vinyl records can be improved through certain accessories and cleaning supplies. Slipmats provide a soft and cushioned surface between the record and the turntable platter, minimizing friction and preventing potential scratches or damage to the vinyl surface.[118]

Where old disc recordings are considered to be of artistic or historic interest, from before the era of tape or where no tape master exists, archivists play back the disc on suitable equipment and record the result, typically onto a digital format, which can be copied and manipulated to remove analog flaws without any further damage to the source recording. For example, Nimbus Records uses a specially built horn record player to transfer 78s.[119] Anyone can do this using a standard record player with a suitable pickup, a phono-preamp (pre-amplifier) and a typical personal computer. However, for accurate transfer, professional archivists carefully choose the correct stylus shape and diameter, tracking weight, equalisation curve and other playback parameters and use high-quality analogue-to-digital converters.[120]

As an alternative to playback with a stylus, a recording can be read optically, processed with software that calculates the velocity that the stylus would be moving in the mapped grooves and converted to a digital recording format. This does no further damage to the disc and generally produces a better sound than normal playback. This technique also has the potential to allow for reconstruction of broken or otherwise damaged discs.[121]

Popularity and current status

[edit]

Groove recordings, first designed in the final quarter of the 19th century, held a predominant position for nearly a century—withstanding competition from reel-to-reel tape, the 8-track cartridge, and the compact cassette. The widespread popularity of Sony's Walkman was a factor that contributed to the vinyl's lessening usage in the 1980s.[122]

In 1988, the compact disc surpassed the gramophone record in unit sales. Vinyl records experienced a sudden decline in popularity between 1988 and 1991,[123] when the major label distributors restricted their return policies, which retailers had been relying on to maintain and swap out stocks of relatively unpopular titles. First the distributors began charging retailers more for new products if they returned unsold vinyl, and then they stopped providing any credit at all for returns. Retailers, fearing they would be stuck with anything they ordered, only ordered proven, popular titles that they knew would sell, and devoted more shelf space to CDs and cassettes. Record companies also removed many vinyl titles from production and distribution, further undermining the availability of the format and leading to the closure of pressing plants. This rapid decline in the availability of records accelerated the format's decline in popularity, and is seen by some as a deliberate ploy to make consumers switch to CDs, which unlike today, were more profitable for the record companies.[124][125][126][127]

The more modern CD format held numerous advantages over the record such as its portability, digital audio and its elimination of background hiss and surface noise, instant switching and searching of tracks, longer playing time, lack of continuous degradation (analog formats wear out as they get played),[128] programmability (e.g. shuffle, repeat),[129] and ability to be played on and copied to a personal computer.[130] In spite of their flaws, records continued to have enthusiastic supporters, partly due to a preference of its "warmer" sound and its larger sleeve artwork.[131] Records continued to be format of choice by disc jockeys in dance clubs during the 1990s and 2000s due to its better mixing capabilities.[131]

Revival era

[edit]A niche resurgence of vinyl records began in the late 2000s, mainly among rock fans.[132] The Entertainment Retailers Association in the United Kingdom found in 2011 that consumers were willing to pay on average £16.30 (€19.37, US$25.81) for a single vinyl record, as opposed to £7.82 (€9.30, US$12.38) for a CD and £6.80 (€8.09, US$10.76) for a digital download.[133] The resurgence accelerated throughout the 2010s,[134] and in 2015 reached $416 million revenue in the US, their highest level since 1988.[135] As of 2017, it comprised 14% of all physical album sales.[136] According to the RIAA's midyear report in 2020, phonograph record revenues surpassed those of CDs for the first time since the 1980s.[137]

In 2021, Taylor Swift sold 102,000 copies of her ninth studio album Evermore on vinyl in one week. The sales of the record beat the largest sales in one week on vinyl since Nielsen started tracking vinyl sales in 1991.[138] The sales record was previously held by Jack White, who sold 40,000 copies of his second solo release, Lazaretto, on vinyl in its first week of release in 2014.[139]

Approximately 180 million LP records are produced annually at global pressing plants, as of 2021.[140]

Present production

[edit]

As of 2017[update], 48 record pressing facilities exist worldwide. The increased popularity of the record has led to the investment in new and modern record-pressing machines.[141] Only two producers of lacquer master discs remain: Apollo Masters in California, and MDC in Japan.[142] On 6 February 2020, a fire destroyed the Apollo Masters plant. According to the Apollo Masters website, their future is still uncertain.[143] Hand Drawn Pressing opened in 2016 as the world's first fully automated record pressing plant.[144]

Less common recording formats

[edit]VinylVideo

[edit]VinylVideo is a format to store a low resolution black and white video on a vinyl record alongside encoded audio.[145][146][147]

Capacitance Electronic Disc

[edit]Another example is the Capacitance Electronic Disc, a color video format, slightly better than VHS.[148]

See also

[edit]- Album cover

- Apollo Masters Corporation fire

- Capacitance Electronic Disc

- Conservation and restoration of vinyl discs

- Electrical transcription

- LP record

- The New Face of Vinyl: Youth's Digital Devolution (photo documentary)

- Phonograph cylinder

- Record Store Day

- Sound recording and reproduction

- Unusual types of gramophone records

References

[edit]- ^ It's almost final for vinyl: Record manufacturers dwindle in the U.S. Archived 16 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Kitchener – Waterloo Record – Kitchener, Ont., 9 January 1991.

- ^ "Millennials push 2015 record sales to 26-year high in US". NME.COM. Archived from the original on 26 December 2015.

- ^ "Vinyl sales pass 1m for first time this century". Wired UK. Archived from the original on 20 April 2016.

- ^ Caulfield, Keith (11 January 2023). "U.S. Vinyl Album Sales Rise for 17th Straight Year — But Growth Is Slowing". Billboard. Retrieved 4 May 2024.

- ^ The 2 slower speeds used by the Library of Congress to supply the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped.

- ^ Bob Evans (8 November 1999). "A Whole New Ball Game". Information Week. p. 176.

when broken or scratched ... repeating the same music or words over and over again

- ^ Deb Amlen (7 October 2011). "Saturday: Sounds Like a Broken Record". The New York Times.

repetitive sounds .. this means the record SKIPS its groove

- ^ "Dictionary.com | Meanings & Definitions of English Words". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 4 May 2024.

- ^ "SAA Dictionary: platter". dictionary.archivists.org. Retrieved 4 May 2024.

- ^ "vinyl | Etymology of vinyl by etymonline". www.etymonline.com. Retrieved 4 May 2024.

- ^ "licorice pizza". TheFreeDictionary.com. Retrieved 4 May 2024.

- ^ "mar 25, 1857 - Phonautograph invented". Time. Archived from the original on 29 June 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ "Origins of Sound Recording: The Inventors: Edouard-Léon Scott de Martinville: The Phonautograph". National Park Service. 17 July 2017. Archived from the original on 6 March 2023. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ Fabry, Merrill (1 May 2018). "What Was the First Sound Ever Recorded by a Machine?". Time. Archived from the original on 7 June 2022. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- ^ "Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville". First Sounds. 2008. Archived from the original on 1 July 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ Nineeenth-century Scientific Instruments. University of California Press. 1983. p. 137. ISBN 9780520051607. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017.

- ^ "The Life of Thomas A. Edison". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 20 January 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ "History of the Cylinder Phonograph". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ Wallace, Robert (17 November 1952). "First It Said 'Mary'". LIFE. pp. 87–102.

- ^ "Centennial of Broadcasting in Canada". Canadashistory.ca. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ Ober, Norman (1973). "You Can Thank Emil Berliner for the Shape Your Record Collection Is In". Music Educators Journal, Vol. 60, No. 4 (December 1973), pp. 38–40.

- ^ Read, Oliver (1952). "History of Acoustical Recording". The Recording and Reproduction of Sound (revised and enlarged 2nd ed.). Indianapolis: Howard W. Sams. pp. 12, 14, 15.

- ^ a b Copeland, Peter (2008). Manual of Analogue Audio Restoration Techniques (PDF). London: British Library. pp. 89–90. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- ^ "Pro Audio Reference". 78 rpm record. Retrieved 8 August 2024.

- ^ Frank Andrews; Arthur Badrock; Edward S. Walker (1992). World Records, Vocalion "W" Fetherflex and Penny Phono Recordings: A listing. Spalding, Lincolnshire: The Authors.

- ^ Scholes, plate 73.

- ^ Rick Kennedy, Jelly Roll, Bix, and Hoagy: Gennett Studios and the Birth of Recorded Jazz, Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1994, pp. 63–64.

- ^ A photograph of the Gennett Records studio is available. "nick lucas playing with bailey's lucky seven at gennett studios". Nick Lucas. Archived from the original on 29 May 2008. Retrieved 9 April 2008.

- ^ a b Jacques Chailley – 40,000 Years of Music: Man in Search of Music – 1964 p. 144, "On March 21st, 1925, Alfred Cortot made for the Victor Talking Machine Co., in Camden, New Jersey, the first classical recording to employ a new technique, thanks to which the gramophone was to play an important part in musical life: electric ..."

- ^ Whelan, M.; Kornrumpf, W. (2014). "Vacuum Tubes (Valves)". Edison Tech Center. Archived from the original on 2 February 2015. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ Wanamaker (16 January 1926). Wanamaker's ad in The New York Times, 16 January 1926, p. 16.

- ^ Pakenham, Compton (1930), "Recorded Music: A Wide Range". The New York Times, February 23, 1930, p. 118

- ^ "Nazi Era Flexi Discs". Bone Music. 19 July 2020. Archived from the original on 6 February 2023. Retrieved 6 February 2023.

- ^ The New York Times (1925-10-07). "New Music Machine Thrills All Hearers At First Test Here". Archived 2013-05-10 at the Wayback Machine Front page.

- ^ "LPs historic". Musicinthemail.com. Archived from the original on 26 April 2016. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- ^ Read, Oliver; Welch, Walter L., From Tin Foil to Stereo, U.S., 1959

- ^ V-Disc and Armed Forces Radio Catalogue, Blue Goose Publishers, St Louis

- ^ The Amazing Phonograph, Morgan Wright, 2002 Hoy Hoy Publishers, Saratoga Springs, NY p. 65

- ^ Millard, Andre (1995). America on Record: A History of Recorded Sound. Cambridge University Press. p. 353. ISBN 0-521-47556-2 – via Internet Archive.

record playing time.

- ^ Welch, Walter L.; Burt, Leah (1994). From Tinfoil to Stereo: The Acoustic Years of the Recording Industry, 1877–1929. University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1317-8.

- ^ Allain, Rhett (11 July 2014). "Why Are Songs on the Radio About the Same Length?". Wired. Archived from the original on 11 July 2014. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

- ^ "Louis Armstrong and King Oliver", Heritage Jazz, cassette, 1993

- ^ Eddie Condon, "We Called It Music", Da Capo Press, New York, 1992, p. 263–264. (Originally published 1947)

- ^ Back cover notes, "Jammin' at Commodore with Eddie Condon and His Windy City Seven...", Commodore Jazz Classics (CD), CCD 7007, 1988

- ^ "Hits of the 1920s, Vol. 2 (1921–1923)". Naxos.com. Archived from the original on 25 January 2016. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- ^ a b "Recording Technology History". University of San Diego. Archived from the original on 29 March 2007. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- ^ "On This Date..." Songs By Sinatra. Archived from the original on 3 April 2005.

Enter May 28 See bottom.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Paul Whiteman and his Orchestra". Redhotjazz.com. Archived from the original on 5 January 2012. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ^ "History of Record Albums".

- ^ "Billboard". Books.google.com. 25 May 1968. p. 3. Archived from the original on 9 May 2016. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- ^ "Billboard". Books.google.com. 23 November 1968. p. 10. Archived from the original on 4 June 2016. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- ^ "The Beatles at 78 RPM". Cool78s.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- ^ "The invention of vinyl records - where it began". Archived from the original on 4 April 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ^ "Peyton On Patton | Rev. Peyton's Big Damn Band". Bigdamnband.com. 5 May 2011. Archived from the original on 7 May 2011. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- ^ Goldmark, Peter. Maverick inventor; My Turbulent Years at CBS. New York: Saturday Review Press, 1973.

- ^ Ben Sisario (6 October 2012). "Howard H. Scott, a Developer of the LP, Dies at 92". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

Howard H. Scott, who was part of the team at Columbia Records that introduced the long-playing vinyl record in 1948 before going on to produce albums with the New York Philharmonic, Glenn Gould, Isaac Stern and many other giants of classical music, died on Sept. 22 in Reading, Pa. He was 92. ...

- ^ a b "Columbia Diskery, CBS Show Microgroove Platters to Press; Tell How It Began" (PDF). Billboard. 26 June 1948. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 22 June 2022..

- ^ The First Long-Playing Disc Library of Congress (Congress.gov) (accessdate 21 June 2021)

- ^ Marmorstein, Gary. The Label: The Story of Columbia Records. New York: Thunder's Mouth Press; p. 165.

- ^ Peter A Soderbergh, "Olde Records Price Guide 1900–1947", Wallace–Homestead Book Company, Des Moines, Iowa, 1980, pp. 193–194.

- ^ Williams, Trevor I. (1982). A Short History of Twentieth-Century Technology, c. 1900 – c. 1950. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-858159-9.

- ^ "The War of the Speeds". 16 August 2022.

- ^ a b c "The 45 Adaptor". ARChive of Contemporary Music, or "Would You Take My Mind Out for a Walk". 20 March 2008. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016.

- ^ a b c (Book), "Frank Sinatra: The Columbia Years: 1943–1952: The Complete Recordings", unnumbered at back.

- ^ Gorman, Robert (May 1949). "What's What in the Platter Battle". Popular Science. 154 (5). Bonnier Corporation: 132–133. ISSN 0161-7370.

- ^ Soderbergh, p. 194.

- ^ Biro, Nick (20 July 1959). "Seeburg Background Music Move Part of Diversification Program". Billboard. New York. p. 67.

- ^ "RCA SelectaVision VideoDisc FAQ". Cedmagic.com. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- ^ Morton, David L. Jr. (2006). Sound recording: the life story of a technology. Greenwood technographies. JHU Press. p. 94. ISBN 0-8018-8398-9. Archived from the original on 10 May 2016.

- ^ Spanias, Andreas; Painter, Ted; Atti, Venkatraman (2007). Audio signal processing and coding. Wiley-Interscience. p. xv–xvi. ISBN 978-0-471-79147-8. Archived from the original on 11 May 2016.

- ^ a b "Stereo disc recording". Archived from the original on 25 September 2006. Retrieved 4 October 2006.

- ^ Reed, Peter Hugh (1958). American record guide, p. 205.

- ^ Nakamichi High-Com II Noise Reduction System - Owner's Manual - Bedienungsanleitung - Mode d'Emploi (in English, German, and French). 1980. 0D03897A, O-800820B. Archived from the original on 10 November 2017. Retrieved 10 November 2017. [1] (NB. This compander exists in two identically named but slightly different versions; only one of them has a dedicated "Disk" setting, the other one instead has an additional setting to combine subsonic with MPX filtering. In this model, High-Com II encoded vinyl disks have to be played back through the "Rec" setting of a connected tape deck.)

- ^ The Stillness of Dawn - High-Com II Demonstration Record (A limited edition not-for-sale High Com II encoded audiophile vinyl record and corresponding leaflet. This LP contains 400 Hz, 0 dB, 200 nWb/m calibration tones as well.). Nakamichi. 1979. NAK-100.

Track list: Side A: Philharmonia Hungarica (Zoltan Rozsnyai): 1. Bizet (Carmen prelude) [2:30] 2. Berlioz (Rákóczi March from Damnation of Faust) [4:40] 3. Rimsky-Korsakov (Procession of the Nobles from Mlada) [4:55] 3. Brahms (Hungarian Dance No. 5) [4:30] 4. 400 Hz calibration tone. [1:00], Side B: S.M.A. Sextet (Sherman Martin Austin): 1. Impressions (John Coltrane) [5:00] 2. Mimosa (Dennis Irwin) [5:52] 3. Little B's Poem (Bobby Hutcherson) [3:12] 4. 400 Hz calibration tone [1:00]. […] Quotes from the sleeve: […] Thousands of man-hours were spent listening, adjusting, optimizing—until harpsichords sound like harpsichords without mutilated transients, until bass viols sound like bass viols without harmonic distortion, until triangles sound lean and crisp without breathiness. The result is High-Com II, the world's finest two-band noise-reduction system. […] High-Com II is the first audiophile noise-reduction system that achieves professional quality. […] Listen especially for the dramatic reduction in surface noise on this High-Com II encoded record. There is no residual hiss; the ticks, pops, and crackles that mar conventional discs are absent. So is turntable rumble. The loud passages emerge with unprecedented clarity since they need not be recorded at so high and distortion-producing a level. […] Between programs, there is utter silence. […] We also suggest you listen closely for sounds of "breathing" and noise pumping. This common fault of noise-reduction systems has been eliminated in High-Com II. Listen also to High-Com II's remarkable ability to accurately preserve musical transients. They are neither muted nor exaggerated nor edgy as with other companders. This accuracy of reproduction—on all types of music, at all frequencies, and at all levels—is what distinguishes High-Com II from other noise-reduction systems. […] Unlike simple companders, High-Com II is optimized differently for signals of different strength and different frequencies. Low-level signals are processed for maximum noise reduction, high-level ones for minimum distortion. This sophisticated technique assumes maximum dynamic range with minimum "breathing" and other audible side effects. […] Sound of extraordinary dynamic range—a background free from surface noise, pops, clicks, rumble, and groove echo—the mightiest crescendo, free from distortion. Sound without breathing, pumping, or other ill side effects.

- ^ Taylor, Matthew "Mat" (19 October 2017). "CX Discs: Better, Worse & the Same as a normal record". Techmoan. Archived from the original on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ^ Hohmuth, Gerhard (1987). "Verbesserte Schallplattenwiedergabe durch UC-Kompressor". radio fernsehen elektronik (rfe) (in German). Vol. 36, no. 5. Berlin: VEB Verlag Technik. pp. 311–313. ISSN 0033-7900. (3 pages) (NB. Includes a description of the UC compander system.)

- ^ a b Milde, Helmut (1987). Written at Dresden, Germany. "Das UC-Kompandersystem" (PDF). radio fernsehen elektronik (rfe) (in German). Vol. 36, no. 9. Berlin, Germany: VEB Verlag Technik. pp. 592–595. ISSN 0033-7900. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2021. (4 pages) (NB. Includes a detailed description of the UC system characteristics and a reference schematic developed by Milde, similar to the circuitry used in the Ziphona HMK-PA2223. According to the author he later also developed an improved version utilizing more modern ICs.)

- ^ a b Wonneberg, Frank [in German] (2000). Vinyl Lexikon - Wahrheit und Legende der Schallplatte - Fachbegriffe, Sammlerlatein und Praxistips (in German) (1 ed.). Lexikon Imprint Verlag. ISBN 3-89602226-1.

UC […] Vom VEB Deutsche Schallplatten und dem ZWT Rundfunk und Fernsehen der DDR entwickelter, breitbandiger Kompander zur Codierung von Schallplatten. Das UC-Kompandersystem (universal compatible) nutzt die Möglichkeit durch den Einsatz sogenannter Logarithmierer, den Verstärkungsvorgang fließend zu gestalten und ein abruptes Umschalten bei niedrigen Signalpegeln zu vermeiden. Durch einen sich kontinuierlich wandelnden Kompressionsgrad von 5:3 (0 dB) bis 1:1 (−20 dB) erzielt man eine effektive Störunterdrückung von 10 dB. Die Expansion erfolgt spiegelverkehrt. Auch ohne den Einsatz eines entsprechenden UC-Expanders bleiben durch das"fließende"Verfahren die Ein- und Ausklingvorgänge in ihrer Homogenität und auch die Raumabbildung der Tonaufzeichnung weitestgehend erhalten. Die gewinnbringende Nutzung des UC-Kompanderverfahrens stellt den Anwender vor ein kaum lösbares Problem, da die ökonomischen Rahmenbedingungen und die zentrale Planung der Geräteentwicklung in der DDR die Herstellung eines Serienproduktes untergruben. Letztlich existieren nur einige Labormuster in den Händen der an dem Verfahren beteiligten Entwickler. Ein Versuch nach 1990, mit dem Verfahren erneut Fuß zu fassen, scheiterte an der international bereits von der Industrie vollzogenen, umfassenden Digitalisierung der Heimwiedergabe. Vom VEB Deutsche Schallplatten wurden in den Jahren 1983 bis 1990 weit mehr als 500 verschiedene UC-codierte Schallplatten der Marken Eterna und Amiga veröffentlicht. Alle entsprechend aufgezeichneten Schallplatten tragen im Spiegel der Auslaufrille zusätzlich zur Matrizengravur ein U. Auf eine äußere, gut sichtbare Kennzeichnung wurde, im Sinne der hervorragenden Kompatibilität des Verfahrens bei einer konventionellen Wiedergabe und in Ermangelung verfügbarer UC-Expander für den Heimgebrauch, verzichtet.

- ^ a b Müller, Claus (2018). Meinhardt, Käthe (ed.). "UC-Expander" (in German). Archived from the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2021. p. 4:

[…] In den 1980er Jahren wurden in der DDR vom VEB Deutsche Schallplatten unter dem Label ETERNA viele sehr gute Aufnahmen klassischer Musik veröffentlicht. Diese Platten wurden, nicht wie sonst üblich, in Lackfolie sondern direkt in eine Metallscheibe geschnitten (DMM - Direkt Metal Mastering). Das ersparte zwei Zwischenkopien im Produktionsablauf, was nicht nur schneller ging, sondern auch zu einer erheblich besseren Qualität führte. Zur weiteren Steigerung der Klangqualität wurde das UC-Kompandersystem (UC - Universal Compatible) eingesetzt. Damit wurden beim Schneiden der Platte die leisen Töne etwas lauter und die lauten entsprechend leiser überspielt. Wendet man bei der Wiedergabe das umgekehrte Verfahren an, werden mit den leisen Tönen auch die Störungen abgeschwächt und die lauten Stellen verzerren nicht und nutzen sich weniger ab. All das geschah so vorsichtig, dass man die Platte auch ohne Expander bei der Wiedergabe noch genussvoll anhören konnte. Zum Glück, denn es hätte sowieso nur einen Plattenspieler gegeben, der über eine entsprechende Schaltung verfügte und der war sehr teuer. Vermutlich aus diesem Grund hat man auf eine weithin sichtbare Kennzeichnung der mit diesem Verfahren aufgenommenen Platten verzichtet. Nur in der Gravur zwischen den Auslaufrillen kann man am angehängten U den Einsatz des Kompressors erkennen […] Das vorliegende Programm erfüllt die Aufgabe eines UC-Expanders, mit dem Sie eine im wav-format digitalisierte Schallplattenaufnahme bearbeiten können, um nun endlich den Klang genießen zu können, den Sie damals erworben haben. Bis dahin gibt es aber noch eine Schwierigkeit. Zur richtigen Einstellung des Programmes benötigen Sie eine Schallplatte, auf der ein Bezugspegelton aufgezeichnet ist, wie das bei den, dem Plattenspieler beiliegenen, Testplatten der Fall war. […]

(NB. Describes a software implementation of an UC expander as a program "UCExpander.exe" for Microsoft Windows. Also shows a picture of the "U" engraving in the silent inner groove indicating UC encoded vinyl disks.) - ^ Seiffert, Michael; Renz, Martin (eds.). "Ziphona HMK-PA2223". Hifi-Museum. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 6 May 2021. [2][3][4][5][6] (NB. Has pictures of a VEB Phonotechnik Pirna/Zittau Ziphona HMK-PA2223, a tangential arm direct drive turntable with built-in UC expander, with the frontpanel showing a "UC" logo (for "Universal Compander").)

- ^ a b "Bulletin E 3: Standards for Stereophonic Disc Records". Aardvark Mastering. RIAA. 16 October 1963. Archived from the original on 15 November 2014. Retrieved 10 November 2014.

- ^ "Little Wonder Records, Bubble Books, Emerson, Victor, Harper, Columbia, Waterson, Berlin and Snyder". Littlewonderrecords.com. Archived from the original on 20 April 2016. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- ^ "Supplement No. 2 to NAB (NARTB) Engineering Handbook; NARTB Recording and Reproducing Standards" (PDF). 1953.

- ^ Columbia Record Catalog 1950

- ^ Columbia record catalog Aug 1949

- ^ The Fabulous Victrola 45 Phil Vourtsis

- ^ Indiana State Museum document no. 71.2010.098.0001

- ^ Paphides, Pete (29 January 2015). "Bone music: the Soviet bootleg records pressed on x-rays". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 9 September 2024.

- ^ "The curious tale of Bhutan's playable record postage stamps". The Vinyl Factory. 30 December 2015. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017.

- ^ Hogan, Marc (11 April 2018). "'High Definition Vinyl' Is Happening, Possibly as Early as Next Year". Pitchfork. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- ^ Rose, Brent (20 April 2018). "What Is HD Vinyl and Is It Legit?". Gizmodo. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- ^ Seppala, Timothy J. (26 April 2018). "HD vinyl is a promise, not a product". Endgadget. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- ^ "HD Vinyl Takes Next Step with Debut of 3D Topography Software Perfect Groove". Making Vinyl. 4 April 2019. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ " "Making Vinyl Europe – Program – Meistersaal, Berlin". Making Vinyl. 2 May 2019. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ Bayly, Ernie (February 1976). "Double-sided records". The Talking Machine Review International (38). Ernie Bayly, Bournemouth: 596–597.

- ^ Adrian Hope (24 January 1980). "Pressing Problems for a Record Future". New Scientist. p. 229 ff.

- ^ "Record Collectors Guild on Dynaflex". The Record Collectors Guild. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007.

- ^ Fritz, Jose. "180 grams " Archived 27 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Arcane Radio Trivia, 23 January 2009. Accessed 26 January 2009. "The basic measurement behind those grams is thickness. It's been said to be less noisy, which really has more to do with the grade of vinyl."

- ^ Mcdill, Stuart (21 September 2022). "Bioplastic records could help decarbonise music business, says developer". Reuters. Thomson Reuters Corporation. Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- ^ Dredge, Stuart (28 September 2023). "Sonopress and WMG launch sustainable 'EcoRecord' vinyl". Music Ally. Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- ^ "BBC - Music - Vinyl". Archived from the original on 15 March 2008. Retrieved 22 June 2008.

- ^ "The Official UK Charts Company : ALBUM CHART HISTORY: An Introduction". Archived from the original on 17 October 2008. Retrieved 22 June 2008.

- ^ Shay Sayre, Cynthia King, Entertainment and Society: Influences, Impacts, and Innovations (2010), p. 558: "The phrase 'sounding like a broken record' has been used to describe a person who says the same thing over and over again; the reference is to old records that would skip and repeat owing to scratch marks on the vinyl."

- ^ "Comparative tables for 30 cm LP Standards". A.biglobe.ne.jp. Archived from the original on 5 August 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ^ Guttenberg, Steve. "Do vinyl LPs wear out? The Audiophiliac takes on that myth". CNET. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ "4. How Long Can You Store CDs and DVDs and Use Them Again?". Clir.org. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- ^ "How To Organize Vinyl Records: Tips, Tricks & Suggestions". premier-recordsinc.com. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ Alexandrovich, George (1987). "Disc Recording and Playback". In Glen Ballou (ed.). Handbook for Sound Engineers: The New Audio Cyclopedia. Howard W. Sams & Company. pp. 873–882, 897. ISBN 0-672-21983-2.

- ^ Self, Douglas (2002). Small Signal Audio Design. Taylor & Francis. p. 254. ISBN 0240521773. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016.

- ^ "Audacity Team Forum: Pre-echo when recording vinyl record". Audacityteam.org. Archived from the original on 9 June 2009. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ^ Dunning, Brian (19 December 2015). "inFact: Vinyl vs Digital". YouTube. Archived from the original on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- ^ Morgan, Katrina (11 October 2017). "Which Sounds Better, Analog or Digital Music?". Scientific American. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- ^ Feldman, Len (December 1979). "DBX-encoded discs—records without noise". Popular Science. Vol. 215, no. 6. p. 93 – via Google Books.

- ^ Howard, Keith (5 February 2006). "Ringing False: Digital Audio's Ubiquitous Filter". Stereophile. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- ^ Cutnell, John D.; Johnson, Kenneth W. (1997). Physics. 4th ed. Wiley. p. 466. ISBN 0-471-19112-4.

- ^ "Sonic Science: The High-Frequency Hearing Test". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 24 October 2017. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ "Disc Recording and Playback". In Glen Ballou (editor), Handbook for Sound Engineers: The New Audio Cyclopedia: Howard W. Sams & Company. p. 1037 §27.9.4. ISBN 0-672-21983-2

- ^ ECL (7 April 2024). "The Resurgence of Vinyl Records: Why They're Making a Comeback and How to Start Your Collection". Eclectico. Retrieved 27 April 2024.

- ^ "The Transfer Session". Archived from the original on 20 November 2005. Retrieved 18 September 2005.

- ^ "Guidelines on the Production and Preservation of Digital Audio Objects (IASA TC04)". Iasa-web.org. 21 September 2012. Archived from the original on 8 May 2015. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ^ Fadeyev, V.; C. Haber (2003). "Reconstruction of mechanically recorded sound by image processing" (PDF). Audio Engineering Society. 51 (December): 1172. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 May 2005.

- ^ "FEATURE: Forty Years of the Sony Walkman: 1st July, 1979: An Historic and Iconic Day for Music". Music Musings & Such. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- ^ Sources vary on the actual dates.

- ^ Browne, David (4 October 1991). "A Vinyl Farewell". Entertainment Weekly. No. 86.

- ^ Souvignier, Todd (2004). The World of DJs and the Turntable Culture. Hal Leonard Corporation. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-0-634-05833-2.

- ^ Negativland. "Shiny, Aluminum, Plastic, and Digital" – via urbigenous.net.

- ^ Plasketes, George (1992). "Romancing the Record: The Vinyl De-Evolution and Subcultural Evolution". Journal of Popular Culture. 26 (1): 110,112. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3840.1992.00109.x.

- ^ Rockwell, John (10 March 1985). "INVASION OF THE COMPACT DISKS". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 4 May 2024.

- ^ "DEMYSTIFYING COMPACT DISC PLAYERS". Deseret News. 29 January 2024. Retrieved 4 May 2024.

- ^ "Stealth war against CD piracy". 4 September 2001. Retrieved 4 May 2024.

- ^ a b "BBC News | ENTERTAINMENT | The non-compact disc turns 50". news.bbc.co.uk. 19 July 1998. Retrieved 4 May 2024.

- ^ Swedish public service television teletext, 12.December.2016, page 150 "SVT Text - Sida 150". Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2016. in Swedish (original text) – "Allt fler köper vinylskivor. Trenden med att köpa vinylskivor fortsätter. Sedan 2006 har försäljningen globalt ökat från drygt 3,1 miljoner sålda exemplar jämfört med 31,5 miljoner sålda exemplar 2015. Trots att allt fler vinylskivor säljs är det dock bara en väldigt liten del av skivförsäljningen. I Sverige såldes det förra året 384.000 vinylskivor jämfört med 3.342.000 cd-skivor. De artister som säljer mest är oftast äldre artister och skivor. Mest såld i år är David Bowies sista skiva Black-star. Andra populära artister är Beatles, Led Zeppelin och Adele." – or in English – "More and more buy vinyl records. The trend to buy vinyl records continues. Since 2006 has the global sales increased from approximately 3.1 million sold records to 31.5 million in 2015. Despite this, is it still a small part of the total record sale. In Sweden was 384.000 vinyl records sold last year (=2015) compared to 3.342.000 CD records. The artists who sell most ar usually older artists and records.(comment - bad Swedish in original text is reflected and translated) Most sold in this year (=2016) was David Bowie's last record, Black-star. Other popular artists are Beatles, Led Zeppelin and Adele" (a screenshot of the teletext page exist and can be uploaded, if allowed at Commons and if requested).

- ^ "Vinyl sales up 55%". Thecmuwebsite.com. Archived from the original on 22 March 2016. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- ^ "Record Store Day: This is what happens inside a vinyl factory - BBC Newsbeat". BBC News. 15 April 2016. Archived from the original on 18 April 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ "Vinyl Record Sales At A 28 Year High". Fortune.com. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ "2017 U.S. Music Year-End Report". Nielsen. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- ^ "Vinyl Outsells CDs For the First Time in Decades". 10 September 2020. Archived from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- ^ McIntyre, Hugh. "Taylor Swift's 'Evermore' Is The First Album To Sell 100,000 Vinyl Copies In One Week In U.S. History". Forbes. Retrieved 4 May 2024.

- ^ Cooper, Leonie (18 June 2014). "Jack White breaks US vinyl sales record with 'Lazaretto'". NME. Retrieved 4 May 2024.

- ^ Leimkuehler, Matthew. "How much did vinyl music sales grow in 2021? (Hint: a lot)". The Tennessean. Retrieved 4 May 2024.

- ^ Meet the Record-Pressing Robot Fueling Record's Comeback. Archived 8 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Don't Call It Vinyl Cutting. DJBROADCAST. Archived 23 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Apollo Masters lacquer record discs". Apollomasters.com. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- ^ Setaro, Shawn (30 November 2016). "Hand Drawn Pressing Brings New Technology To Vinyl Records". Forbes. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- ^ Czukay, Holger (23 March 2018) [2017]. "Cinema" (Limited ed.). Grönland Records. LPGRON180. Archived from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2021. [7] (NB. Retrospective box set containing 5 LPs (compilation), 1 DVD-V, 1 VinylVideo 7"-single ("Fragrance", "Holger on his first video recording", "Holger and Jaki"), a digital audio download code and a booklet. The CD version of the set (CDGRON180) does not contain the VinylVideo record.)

- ^ Riddle, Randy A. (29 July 2018). "Vinyl Video". Randy Collects. Archived from the original on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ Taylor, Matthew "Mat" (17 September 2018). "VinylVideo - Playing video from a 45rpm record". Techmoan. Archived from the original on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2021. [8][9]

- ^ "RCA SelectaVision VideoDisc FAQ - What are the technical specifications of the RCA VideoDisc system?". CEDMagic.com. Retrieved 7 March 2007.

Further reading

[edit]- Fadeyev, V.; C. Haber (2003). "Reconstruction of mechanically recorded sound by image processing" (PDF). Audio Engineering Society. 51 (December): 1172.

- Lawrence, Harold; "Mercury Living Presence". Compact disc liner notes. Bartók, Antal Dorati, Mercury 432 017–2. 1991.

- International standard IEC 60098: Analogue audio disk records and reproducing equipment. Third edition, International Electrotechnical Commission, 1987.

- College Physics, Sears, Zemansky, Young, 1974, LOC #73-21135, chapter: "Acoustic Phenomena"

- Powell, James R., Jr. The Audiophile's Technical Guide to 78 rpm, Transcription, and Microgroove Recordings. 1992; Gramophone Adventures, Portage, MI. ISBN 0-9634921-2-8

- Powell, James R., Jr. Broadcast Transcription Discs. 2001; Gramophone Adventures, Portage, MI. ISBN 0-9634921-4-4

- Powell, James R., Jr. and Randall G. Stehle. Playback Equalizer Settings for 78 rpm Recordings. Third Edition. 1993, 2001, 2007; Gramophone Adventures, Portage, MI. ISBN 0-9634921-3-6

- Scholes, Percy A. The Oxford Companion to Music. Ninth edition, Oxford University Press, 1955.

- From Tin Foil to Stereo: Evolution of the Phonograph by Oliver Read and Walter L. Welch

- The Fabulous Phonograph by Roland Gelatt, published by Cassell & Company, 1954 rev. 1977 ISBN 0-304-29904-9

- Where Have All the Good Times Gone?: The Rise and Fall of the Record Industry Louis Barfe.

- Pressing the LP Record by Ellingham, Niel, published at 1 Bruach Lane, PH16 5DG, Scotland.

- Sound Recordings by Peter Copeland published 1991 by the British Library ISBN 0-7123-0225-5.

- Vinyl: A History of the Analogue Record by Richard Osborne. Ashgate, 2012. ISBN 978-1-4094-4027-7.

- "A Record Changer and Record of Complementary Design" by B. H. Carson, A. D. Burt, and H. I. Reiskind, RCA Review, June 1949

- "Recording Technology History: notes revised July 6, 2005, by Steven Schoenherr", University of San Diego (archived 2010)

- Williams, Gavin. Format Friction: Perspectives on the Shellac Disc, University of Chicago Press, 2024

External links

[edit]- How do vinyl record works at vinyl-place website

- Playback equalization for 78 rpm shellacs and early LPs (EQ curves, index of record labels): Audacity Wiki

- The manufacturing and production of shellac records. Educational video, 1942.

- Reproduction of 78 rpm records including equalization data for different makes of 78s and LPs.

- The Secret Society of Lathe Trolls, a site devoted to all aspects of the making of Gramophone records.

- How to digitize gramophone records: Audacity Tutorial

- Actual list of vinyl pressing plants: vinyl-pressing-plants.com

- Dedicated museum for sound history: Musée des ondes Emile Berliner, Montreal, Canada

- Smart Vinyl: The First Computerized

- Semi-automatic metadata extraction from shellac and vinyl disc

- Vinyl Player 2.0